Rangiriri Pā

Description

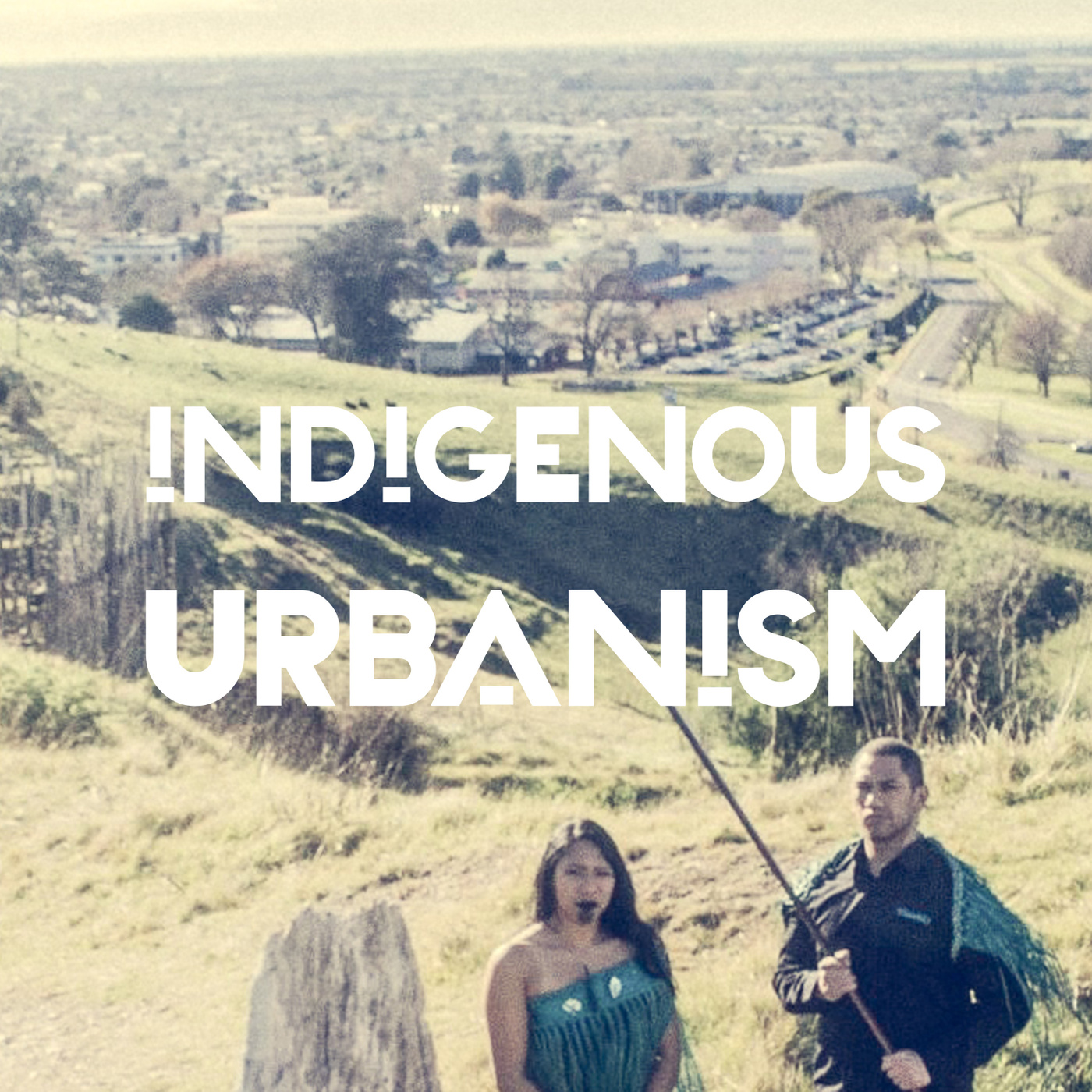

EPISODE SUMMARY: On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism we visit Rangiriri Pā, and the site of a new symbolic reinterpretation developed in reverence to the original pā footprint, and as a setting for continued education about the Battle of Rangiriri and the subsequent invasion of the Waikato.

GUESTS: Moko Tauriki, Dean Whiting, Sam Bourne

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

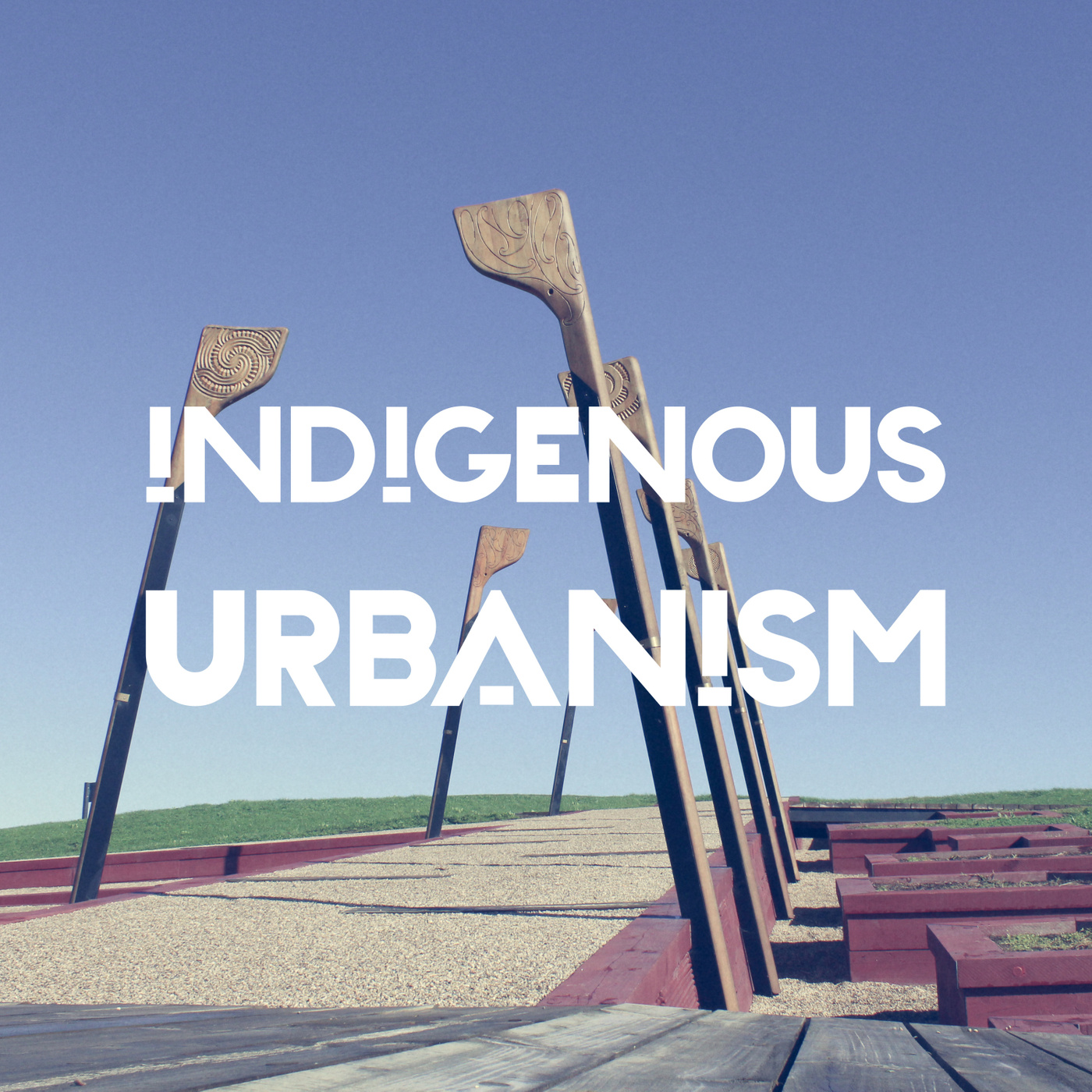

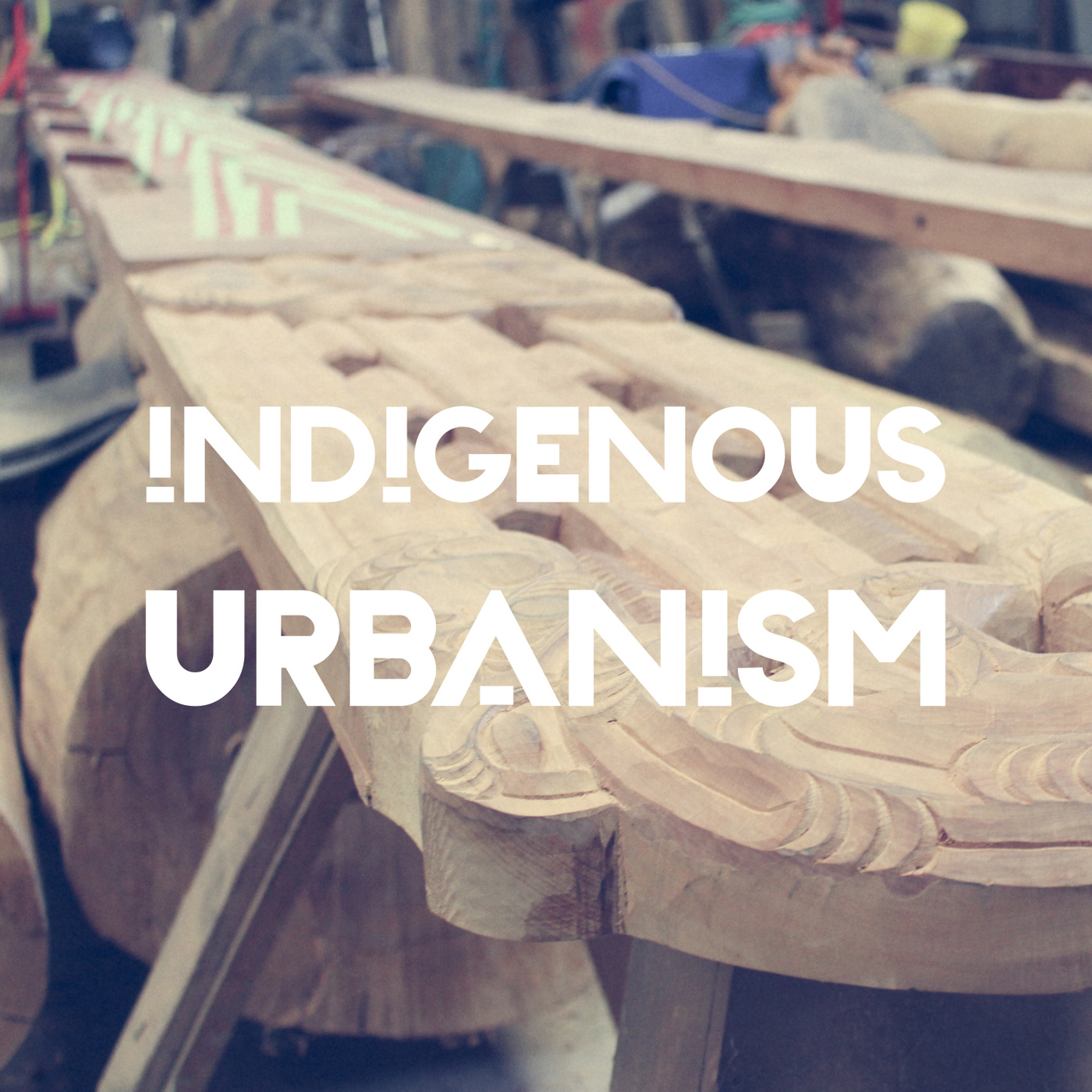

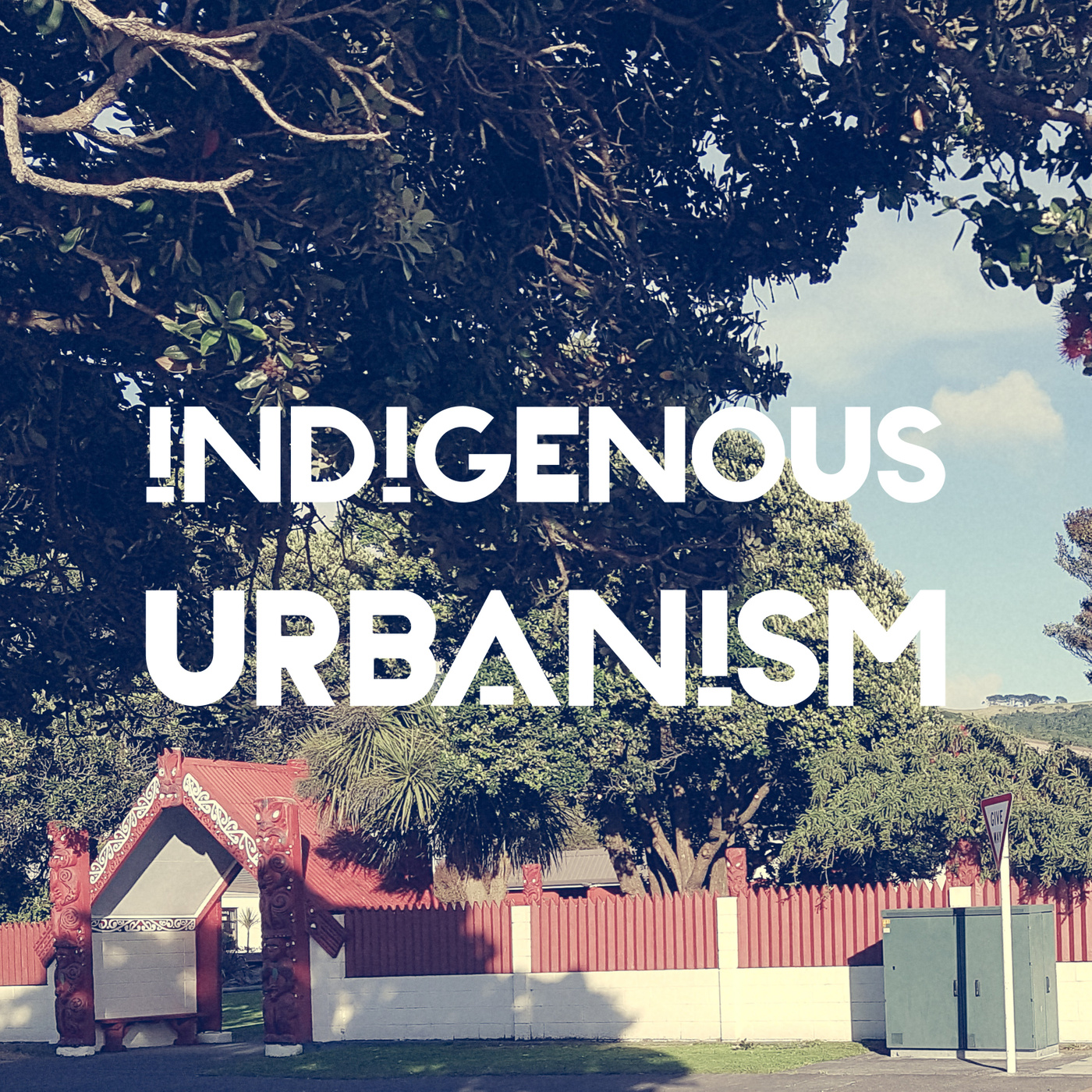

Jade Kake: If you look over to your right on State Highway 1, about 45 minutes north of Hamilton, you’ll see a site of cultural and historical significance. The wetlands and Pou mark the site of a pivotal battle in the 1863 Waikato land wars - The Battle of Rangiriri.

Dean Whiting: So where we're standing at the moment, Rangiriri Pā, so this was the pā that, where one of the major battles, Waikato-Tainui and the British troops that were coming through from Auckland. So there were a series of battles that happened down that line.

JK: In more modern times the significance of the site was overshadowed by the expansion of State Highway 1.

DW: There was a huge cutting through the space, that cut right through the centre of the Pā site.

JK: But now a collaboration between Waikato-Tainui, the New Zealand Transport Agency, and Heritage New Zealand has seen the repatriation of this significant site.

Sam Bourne: When the opportunity came up to re-align State Highway one, that also opened up this opportunity to reimagine and acknowledge the damage that had been done in the past to the pā site, but also make that lineal infrastructure in service to that cultural landscape, and the story of Rangiriri, and the story of the battle that took place there.

JK: Tēnā koutou katoa

Nau mai haere mai ki te Indigenous Urbanism, Aotearoa Edition, Episode 12.

I’m your host Jade Kake and this is Indigenous Urbanism, stories about the spaces we inhabit, and the community drivers and practitioners who are shaping those environments and decolonising through design.

On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism we visit historic Rangiriri Pā, and the site of a new symbolic reinterpretation developed in reverence to the original pā footprint, and as a setting for continued education about the Battle of Rangiriri and the subsequent invasion of the Waikato.

We spoke with Moko Tauariki nō Ngati Naho, who was the Waikato-Tainui lead for the Project.

Kia ora Moko. Thank you so much for agreeing to be on the podcast. Just to start off with, ko wai koe? nō hea koe?

Moko Tauariki: Ko Taupiri te maunga, Waikato te awa, Waikato te iwi, Tainui te waka, Mourea te marae, Ngāti Naho te hapū, ko Moko Tauariki taku ingoa.

JK: Rangiri is a really significant site for Waikato and for all of New Zealand. Could you tell us a little bit about the significance of that site to your hapū and to your wider iwi?

MT: The significance of Rangiriri to Ngāti Naho, Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Pou, Ngāti Mahut - Ngāti Mahuta ki uta - is that it's a place where many of our ancestors stood in defiance of an imminent invasion by the Crown, and basically made their sacrifices there. And so, it's significant to us today because we are actually the kaitiaki that takiwa, of that place, now. Which has been, I guess since the invasion of Rangiriri in 1863, has been under the ownership and the administration, if you like, of the Crown, right up until 2016 when we actually had that particular site handed back to Waikato-Tainui. The invasion into Waikato begins, if you like, at Mercer. That we currently know as Te Pina. And it's probably appropriate for me to focus a little bit on Te Pina, in terms of its significance to Te Puia. And so Te Puia, for many people would know her as the lady who established a cultural kapa haka group called Te Pou o Mangatawhiri. And that group was named after a significant that King Tawhiao did, prior to the invasion of Rangiriri, and he did that on the banks of a stream called the Mangatawhiri stream, which basically is a tributary to the Waikato river. And that became our aukati, or our landmark, and basically signalled to the Crown that you go past this particular landmark, where I have placed my pou, then you declare war. You declare an invasion into Waikato. And so in 1863, General Duncan Cameron, under the orders of Governor Grey, said, well up yours natives, we are the much superior power than you, so we will take this land by force. We challenge you to be rebellious against the Queen of England, and the inception of the Kīngitanga was certainly a threat to that. And so in the month of July, and in actual fact it was on the 12th of July of 1863, Te Pine, or Mercer, was invaded. They then continued to sack, or to invade, occupy other pā sites towards Rangiriri, and in particular Te Tiotio Pā, Te Koheroa Pā, and Meremere Pā. So these are all locations that anybody driving between Auckland and Rangiriri, they would naturally drive past these sites, without a second thought even knowing where they are. The reality is the proximity of where their vehicles is to some of these pā sites, is less than thirty metres. And that's how close it is. We get to Rangiriri in the month of November, the 20th of November, which is when that site was invaded, 1863. Essentially the British tried to take the site by force, were repelled, on several occasions. They then brought some gunships up on the river, that was the only mode of transport, and then decided to bombard their way through, which they essentially did in the end. Rangiriri wasn't just a fort hold, that was held by Waikato-Tainui alone. King, the second Māori King, King Tawhiao, he called on the allegiance of many iwi, all the iwi, from around the motu. He called on that allegiance because his father, the first Māori King Potatau Te Wherowhero, cemented those relationships in a place called Pūkawa, in Taupō. The big event that took place there was called Hinana ki Uta, Hinana ki Tai - search the seas, search the lands, for a king. And on the banks of Pūkawa is where all the rangatira, all the chiefs from around the motu, agreed that Potatau will be King. And then in 1863, Tawhiao was the King, and he called on that allegiance. And so, not all of those iwi came, many of the came. And so Rangiriri is significant to many iwi who actually have ancestors that have actually died there. So, Waikato, our role, we are merely the kaitiaki of that place, to ensure that significance of that particular site, the mauri of that particular site, is retained at the highest level. In 1963, the Crown wanted to build a road. Well they did, they just built their road. The consultation they undertook at that time was nothing more than, this is a piece of paper, it's called the Public Works Act. It says that we can actually do this. And so they used that piece of legislation to just ram through their infrastructure projects, and that's basically how New Zealand, is basically founded, if you like, on that piece of legislation alone, allowing them to do what they needed to do. Our iwi were very opposed to it at the time, signalling, bringing to the Crown's attention that this particular site here at Rangiriri, is a wāhi tapū, and that it shouldn't be messed with. They just said, well, we need to build this road for the public good, so, thank you very much for that -

JK: Too bad Māoris

MT: Yep, too bad Māoris, but we're going to carry on. Koiwi were discovered during the construction phase of that project. We're quite thankful that we had some very significant rangatira still alive at the time, and one of them in particular for Ngāti Maniapoto. His name is Pumi Taituha. And so he was responsible for overseeing the gathering up of those koiwi that were discovered, and returning them back to Taupiri Mountain, our sacred burial mountain, and reburying them there at the rightful place. Because after the Battle of Rangiriri, our people weren't afforded those protocols of having a tangi, they were just simply put over to where was going to be less in the way, if you like, of the colonial troops at that time. And so if they were over in the particular area in the pā site, then they just simply just buried them up and left them there. And then, 2008, the New Zealand Transport Agency, or Transit New Zealand they were called back then, wanted to improve the safety of the State Highway 1 road, and they had identified an alternative route. One of the first things that they said to themselves is that, we better look at how we do this, approach tangata whenua. And so this time, they never lodged a resource consent to build their road. What they decided to do this time around, was actually come and talk to the iwi first. And so, they actually spent near on nearly two years talking with us at Waikato-Tainui, before they even lodged a resource consent for their project. Which is pretty good. And I guess part of their reasoning for that is that they knew that we were going to be very resistant to their plans to build another road through a significant wāhi tapū site. The way and how we worked, we worked in partnership with the New Zealand Transport Agency on that particular project. I set up what's called a tangata whenua working group. And that tangata whenua working group was made up of representatives from the key marae from around that area. Namely, Mourea Marae, Horahora Marae, Waikare Marae, Taniwha Marae, Okaeria Marae. We had māngai from all of those marae, and they were responsible for conveying directly to the agency, their concerns and their views. Which is not typically how some of these things are done. But that's what our CEO at the time, his name was Hemi Rau, that's what he wanted to happen. Sometimes I think the Crown thinks that they should just talk only to the iwi consortium or the so-called iwi authority that's currently in place. That they actually hold the say, but in actual fact that's not the case. The case is that, down in Rangiriri for e