Waimārama Papakāinga

Description

EPISODE SUMMARY: On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism, we continue our haerenga across the Hawke’s Bay to visit a new five house papakāinga development, on the hills of beautiful Waimārama, which for the Renata whānau has been an opportunity to get back to their tūrangawaewae, and to reconnect with their marae and each other.

GUESTS: Paora Sheeran, Eru Smith, Brenda Tatere

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

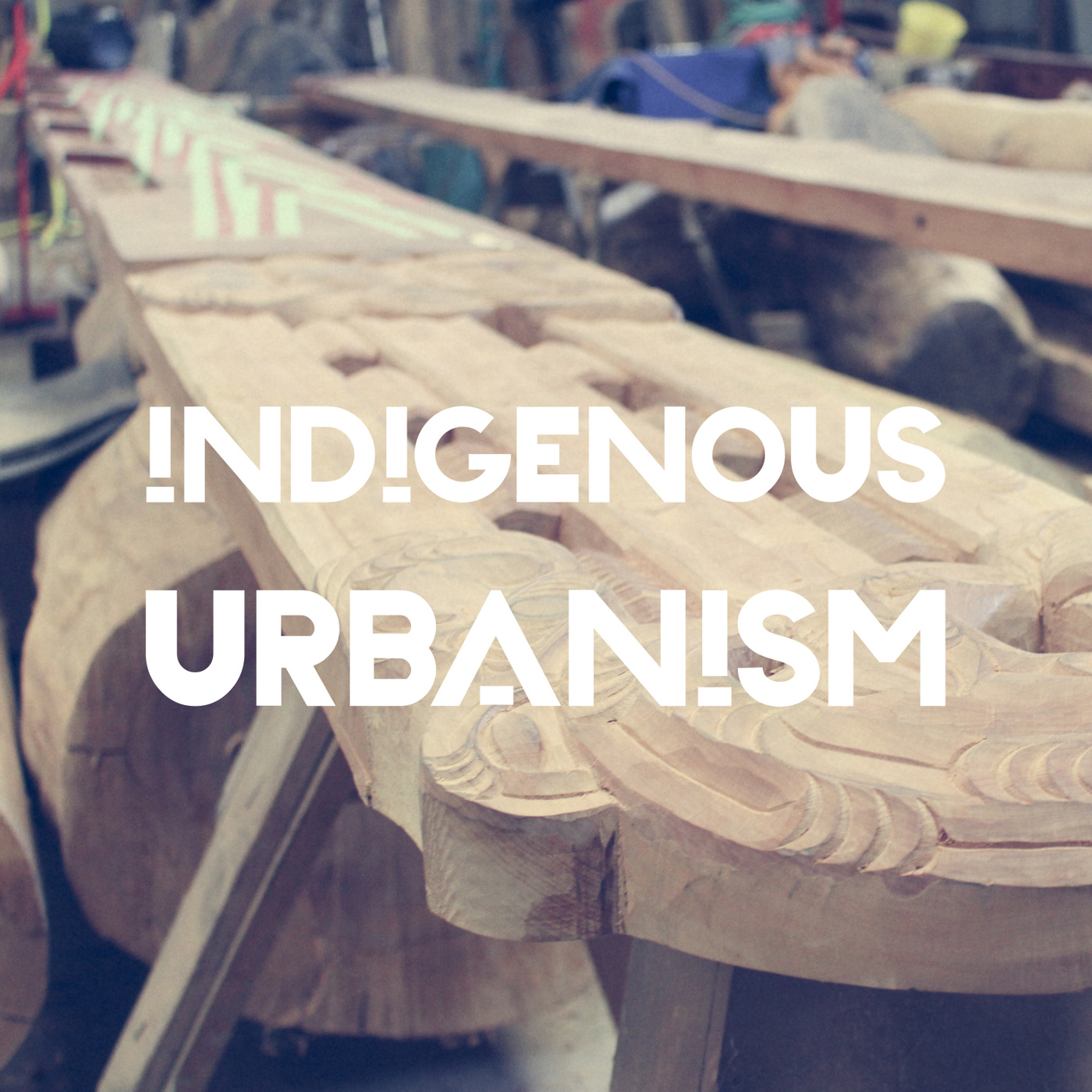

Jade Kake: Picturesque Waimārama. A beautiful seaside community, a place of halcyon summer days, hot chips and ice cream. But it’s not just a lovely holiday destination, it’s also the home of the Ngāti Hikatoa, Ngāti Kurukuru, Ngāti Urakiterangi, and Ngāti Whakaiti hapū of Kahungungu.

In the 1860s the original Waimārama Block, some 35,000 acres, was leased to two European farmers. The promotion and development of Waimārama as a beach lifestyle area started in the early 1900s, when the large farming stations were broken up to create a beach settlement area. Today, the parts of the original Waimārama block that have been retained in Māori ownership are mostly leased out to Pākehā farmers.

For the Renata whānau, the development of papakāinga on their ancestral land is an opportunity to get back to their tūrangawaewae, and to connect with their marae and wider whānau.

Paora Sheeran: If we look over to the right over here, we’ve got a homeowner who moved over from Dannevirke - and I don't know if you remember on the opening day here back in March 2017, and our kaumātua got up and spoke and said that we've been able to return home, you know, so after about I think it was three generations ago, it might have even been four, they had to move away for farming reasons, and now one of the great-great-mokopuna has come back to Waimārama. And not only for her, with that brings back the other whānau.

JK: That's huge.

PS: Yeah, and that's what can happen in papakāinga. There's the hard items, like the houses, the infrastructure, and then there's also the add-on cultural, social benefits.

JK: Tēnā koutou katoa

Nau mai haere mai ki te Indigenous Urbanism, Aotearoa Edition, Episode 15.

I’m your host Jade Kake and this is Indigenous Urbanism, stories about the spaces we inhabit, and the community drivers and practitioners who are shaping those environments and decolonising through design.

On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism: We travel to Heretaunga to visit a new five house papakāinga development, on the hills of beautiful Waimārama. We spoke with Paora Sheeran, a key driver of papakāinga activity in the Hawke’s Bay.

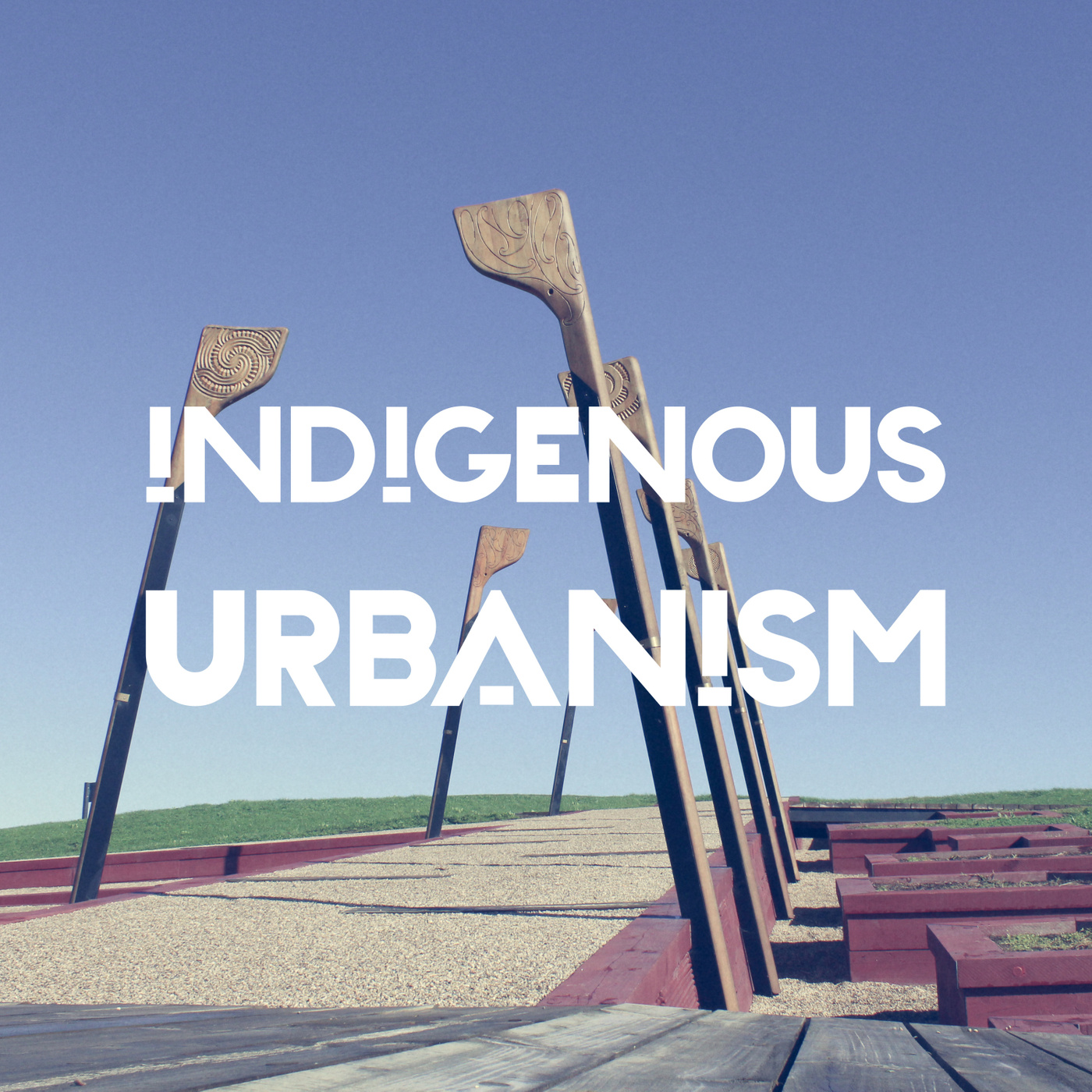

PS: He mihi poto tenei kia a koutou, ko taimai ki Kahungungu nei, otira nō ki Waimārama te whenua nei, tenei whenua o te papakāinga o te whānau Renata, koira te tino tīpuna Renata. Nā reira nau mai. Nau mai haere mai, nau mai hoki mai. Ko wai tenei? Ko Takitimu te waka, ko Ngāti Kahungunu me Ngāti Pahauwera ngā iwi. Ko Rakau Tatahi me Te Rongo a Tahu ngā marae. Ko Ruahine te pai maunga. Ko Te Rangi Tapu Owhata te taumata. Ko Whatumā te waiu. Nā reira, titahi whakatau ki o tou matou nei rohe. Ko Puara kei runga, ko Whatumā kei raro. Tihei, mauri ora. Ko Paul Sheeran tōku ingoa. So we’re in Waimārama, which is in Hawke's Bay, Kahungunu. As you can see it's coastal, we're right on the beach there. This is the Waimārama 3A1C2 Incorporation, and this is their papakāinga.

JK: So we’re up on the hill, overlooking the Ocean. Is that their marae down there?

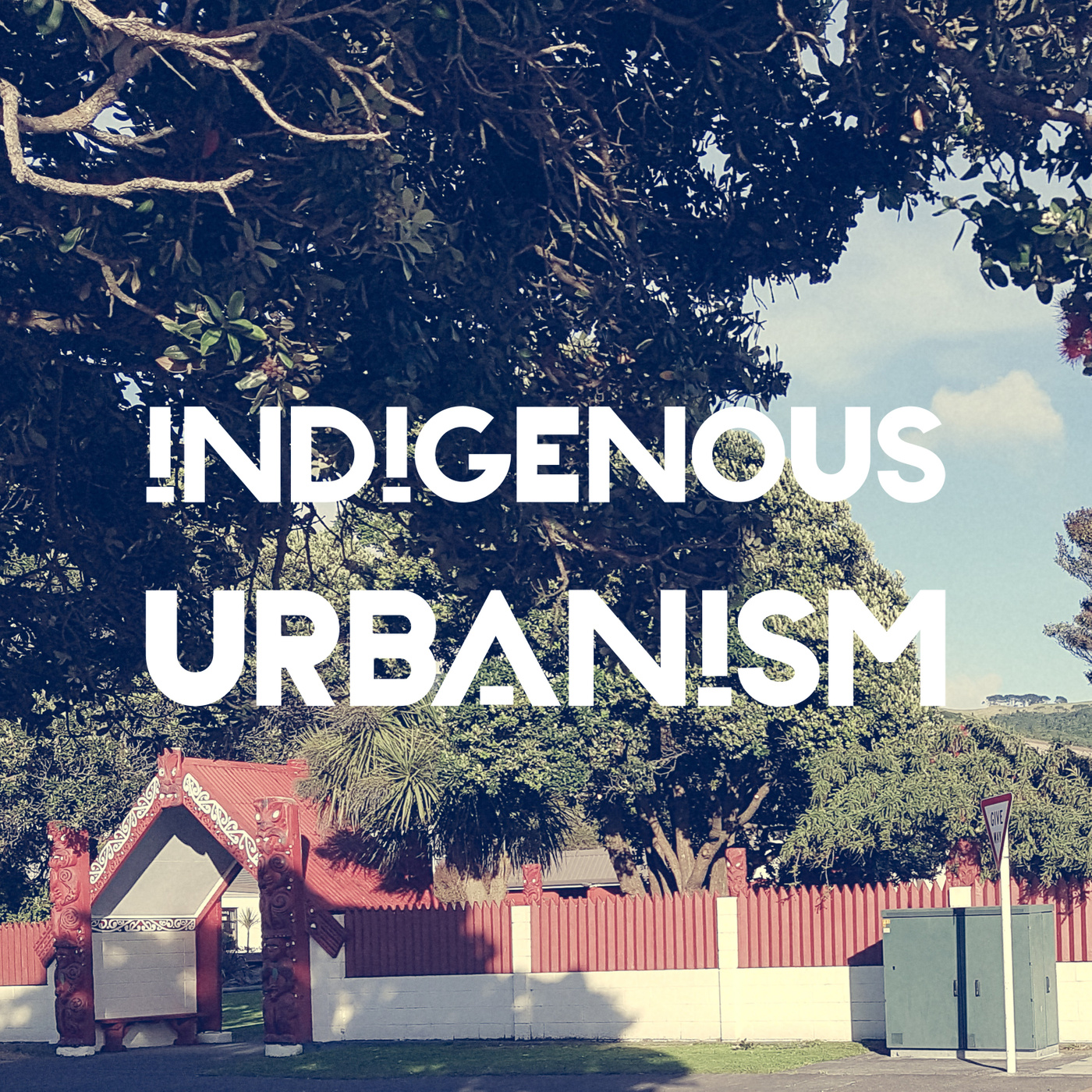

PS: Yes, we've got the marae in the background there. So that was part of the reason why this was such a great site, because the incorporation actually owns a number of lands. And so with the marae just across the road, papakāinga, I think there's a kohanga reo over at the marae as well. So it just, you know, the infrastructure works.

JK: And how many acres or hectares?

PS: Probably looking at 7 hectares for this block.

JK: So the incorporation owns this block as well?

PS: Correct. And then they have a number of other blocks they lease out as well.

JK: Awesome. What are the kind of business things they've got?

PS: Mainly leasing for grazing. As with a lot of Māori freehold land, quite often they’re uneconomic parcels. So, unless you can pull together whānau land around you, or work it a bit more intensely, then you're really just leasing out to the local farmer.

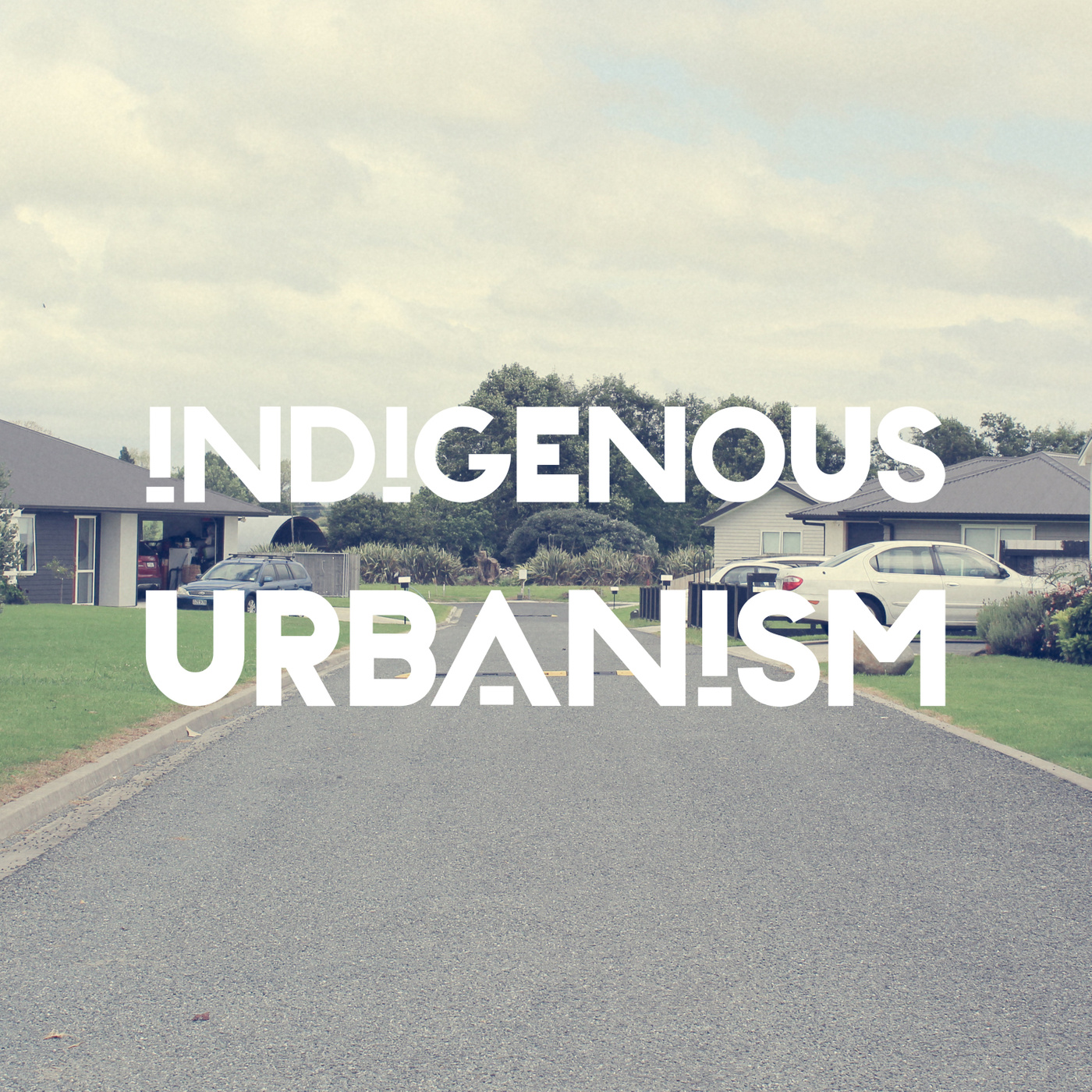

But they chose this site because of the location with the marae, with the Waimārama township as well. Cause of the contours as well. You know, it's got a lot of character, this whenua. When the houses were designed, every kitchen window looks out at Motu-o-kura, which is their maunga, you know, their motu. So that was one of the design features that was sort of incorporated in the house design. So then when all the tamariki are doing the dishes they can talk about their motu. It was a good site. They’ve actually got resource consent to build 20 homes up here, and down on the flats, down below. So this is stage one, and stage one included five houses, so infrastructure for five houses, of which it's a mixed model, ownership. So we've got two home ownership here, and three affordable rentals under the incorporation. And the reason why they started off with five is because when they go back through their whakapapa, there's really five whānau lines. So although they've got a resource consent for 20, they started off with the five so then they could offer each line a house back on their whenua Māori.

PS: So Eru, Eru Smith is the chairperson of the incorporation, he's a kaumātua, well respected kaumātua out here, a man who is well known for getting things done. It's that generation, you know. The phone goes on a Sunday evening, very few words. Kia ora - is this Paul Sheeran? Yes, kia ora. Eru Smith, I hear you do papakāinga. Yes. Good - we want you to help us.

JK: Māori Television’s Te Kaea interviewed Eru Smith at the opening of the papakāinga in March 2017

Eru Smith: It feels great, I feel very proud I suppose. But ah, yeah I'm lucky that I live here too, and my family's from here. But yeah I do, I feel real proud. Out here you could pay anywhere up to $350 a week. So, you know, it's pretty reasonable for living here. And the if you go into the holiday makers they pay up to $1500 a night.

Being back home and being back where you belong I think is one of the main things, but, also that we can support our marae. By being here, so you know, it’s easier to go down and help when help is needed.

JK: And now back to Paora

PS: And so that was in early 2016, we were able to secure feasibility study funding from TPK. As most Māori land is, rural, off-the grid, the only bit of infrastructure that is out here is the water pipe that runs from the reservoir up on the hill out to the beachfront community, the million dollar houses. Not a lot of whānau Māori in those houses. So, we have on site sewerage, we upgraded the power, telecom, a lot of earthworks had to happen here. But yeah, through the TPK grant, it was all possible.

So you’ll notice on the rental properties, so there's two home ownership, three rentals. So we were able to secure some funding to instal the solar panels on the rental properties. It is tied to the grid, so i.e. when you're producing and you're using, that's one for one, that's the savings. But if you're not, if you're producing more than you're using then the excess gets exported back to the grid.

JK: Is it a microgrid at a papakāinga scale, or is it just on the individual?

PS: Individual. So, individual, because each whānau have different levels of power consciousness, if you know what I mean. And so, one whānau might be, they might set all their appliances to go during the day, so that when the sun's at its best and its producing then they're really making the savings. That's something that we try and do on handover, when the whānau takeover, is that we get the solar guy in, and just sort of talk about ways of maximising the savings.

JK: But changing behaviours can be challenging if whānau have never lived in a solar powered home before, for example.

PS: Exactly. And even with living off the grid, like on a water supply, you know, so, you've got to really be conscious of, it's not like in town where you can just turn the tap on and there's water, you know we've got three 25,000 litre tanks here. Goes through a UV filtration system pumped into the houses. But you've still got to be conscious of, in saving water. But you know, you live rural, you just got to be aware of all that.

JK: Yeah actually where I grew up, it was, we were totally off-grid, so we had solar power, and composting toilet, and drew our own rainwater. But it's amazing how those behaviours can be so ingrained, but then the moment you move into town, your behaviour changes a lot.

PS: We're doing another project, on a coastal block of land, and that's been a big part of the conversation throughout the process, is that the whānau coming out, because there are beach units there already, and they always run out of water. So, you imagine taking a whānau from in town out there, used to the constant water flow. So there's got to be a mind change. First home ownership, this house behind us, just gives people the opportunity to move back onto their whenua, close to their marae, in a whanau environment. You'll see down here the communal area that they're sort of slowly developing, which is sort of like the epicentre of most papakāinga, you know, where everyone congregates. But I'd imagine that a lot happens up on these types of levels too.

JK: And are there many kids in this papakāinga?

PS: Yeah. Yeah, there are actually, yeah. So down here, this whānau here moved back from Auckland. You know, house costs up there, rental and the ownership, so they've moved back home. So they've got three