Discover Hardcore Software by Steven Sinofsky (Audio Edition)

Hardcore Software by Steven Sinofsky (Audio Edition)

Hardcore Software by Steven Sinofsky (Audio Edition)

Author: Steven Sinofsky

Subscribed: 10Played: 152Subscribe

Share

© Steven Sinofsky, All Rights Reserved

Description

Personal stories and lessons from inside the rise and fall of the PC revolution as narrated by the author. Sinofsky joined Microsoft in 1989 as a software design engineer on C++. Over the next 23 years he worked across many major products and teams including C++ and Visual C++, Office for six major releases ending as SVP of Office, Windows 7 and Windows 8, as well as most major internet services as President of Windows.

hardcoresoftware.learningbyshipping.com

hardcoresoftware.learningbyshipping.com

109 Episodes

Reverse

Welcome to the final installment of Hardcore Software. It has been an amazing journey in the 115 or so sections including bonus posts. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to those of you that have followed along the journey of the PC and my own growth and lessons. Thank you very very much.I have a few more bonuses planned, including a compendium of Microspeak and a bibliography of books and magazines that I collected. For paid subscribers I will be sending out an update on how billing will end and for “True Blue” subscribers please expect an email on receiving your compiled version of the work. It’s not too late to order that and also have access to all the old posts. I will also be filling in audio for the first 70 posts in early 2023.Hardcore Software describes a personal journey. It is also one that happened to coincide with the PC revolution—the early days all the way through the final days of the revolution. The PC still marches on, but it is different. The PC remains essential though is no longer central to the agenda of computing as it was. That is what I mean by the end of the revolution.This post is free and comments are turned on for all Substack users.Back to 107. Click In With SurfaceWindows 8 was a failure.Hubris. Arrogance. Lunacy. Egomaniacal. Pick any word to describe the product; it was likely used somewhere. No one knew, or felt, the weight of the product failure more than I did.Nearly every successful Microsoft product had survived our it takes three versions to get it right modus operandi. Esther Dyson, a technology investor and journalist, writing for Forbes in an article “Microsoft’s spreadsheet, on its third try, excels” said “It’s something of an industry joke in the software business that it takes Microsoft three tries to get it right. There’s Windows 3.0, Word 3.0, and now Excel 3.0.” She wrote that in 1991, reviewing the third version of Excel.No Windows leader made it through the odd-even curse of releases, certainly not three major releases of Windows from start to finish.My hope had been for a credible Windows 8 knowing we weren’t finished, which was standard operating procedure for new Microsoft products. We knew where we wanted to take the product over time—the hardware, the software, and the apps. But none of that happened. For reasons I still do not fully understand, for the first time I could remember Microsoft quickly and completely withdrew and actively erased Windows 8 in an almost Orwellian way—even Clippy preserved its dignity. I try to imagine what would have happened had Microsoft given up on Windows the first time, or Windows Server, Exchange, Word, Excel, or PowerPoint. All of those took multiple iterations to find product-market fit, to win both hearts and minds.Requiring three versions was not a Microsoft thing. It is a product development thing. Even in a big company you must ship the first version—shipping a “V 1.0” (v for version) is always a miracle. Then you need to fix it and that was version 2.0. Then by version 3.0 not only does the product work, the sales, marketing, positioning, pricing, and more work. Product development is always a journey. Always.With years of hindsight including the new mobile market, the PC market, and Apple, many of the initial problems with Windows 8 were not nearly as egregious as much of the commentary made them out to be. Or maybe the commentary was right and what was egregious was not that we made a product that did what it did, but that we made Windows do those things? Or perhaps we simply did it all too soon? Or that we, surprisingly, lacked patience to get it right?There was commentary on me as a leader, as a person. I knew that was borne of immediate frustration and not enduring. That’s why I remained quiet and did not speak out in 2012 as I moved on to a new experience in Silicon Valley and working with entrepreneurs. I understood and even respected the emotion from where it came and the forces that produced it. Over time individuals who facilitated that commentary have since apologized directly. I was proud to be part of more than two decades of building products, processes, teams, leaders, and people—a culture—that were the highest quality, best equipped, and most talented at Microsoft in the PC era.The problems we needed to solve with Windows 8 and Surface were readily apparent, as I strongly believed the moment we shipped. Nothing anyone wrote about either was surprising or news to those of us who had lived with the products. The commentary on the severity of the problems, and how and what to fix, was debatable.Microsoft had become synonymous with the PC, but could it also reinvent the PC? That was what we set out to do. The problem was that the people who loved PCs the most weren’t interested in a new kind of PC. They wanted the PC to get better, but in the same way it had for decades—primarily, more features for tech enthusiasts and more management and control features for enterprise IT managers. They simply wanted an improved Microsoft PC from Microsoft—launching programs, managing windows, futzing with files, compatibility with everything from the past, and more like that. They wanted more Windows 7.Instead, they got a new era of PC, a modern PC, from other companies, and it would be called iPhone, iPad, Chromebook, or Apple Silicon Macintosh and they would be okay with that. Today in the US, Apple’s device share is off the charts relative to any past. Apple holds greater than majority share of phones. Macintosh is selling at an all-time-high 15-20% of US PCs depending on the quarter. As for the iPad, the device loathed by so many who believed thinking about tablets was the underlying strategic failure of Windows 8, Apple has perhaps 500 million active devices and sells about 160 million iPads per year, or more than half the number of PC sales. The business and personal computing market is no longer the PC market, but vastly larger, and the only position Microsoft maintains is in the part that is shrinking relative to the whole and on an absolute basis.The iPad is worth a special mention because of the tablet narrative that accompanied Apple releasing their product just as we started Windows 8. The iPad had a clear positioning when released—it was between a phone and a PC and great for productivity. It was an odd positioning considering it was precisely a large, but less featured, iPhone. Soon Apple would say the iPad was the embodiment of the future Apple sought. Since then, however, the iPad has been mired in a state of both confusion and poor execution. While taking advantage of the innovation in silicon and the undeniably impressive innovation in Apple’s M-series of chips, the software, tools, frameworks, and peripherals directed at the iPad have, for lack of a better word, failed. For all the unit volumes and significant use as a primary device, it has not yet taken on the role Apple articulated. I would not have predicted where they are today.Jean-Louis Gassée, hired by Steve Jobs and former leader of Apple hardware and later creator of BeOS, had this to say in his wonderfully reflective weekly newsletter, Monday Note:The iPad’s recent creeping “Mac envy”, the abandonment of intuitive intelligibility for dubious “productivity” features reminds one of the proverbial Food Fight Product Strategy: Throw everything at the wall and see what sticks.In competition it takes the leader to drop the ball and someone to be there to pick it up. Whether Apple truly dropped the ball with respect to the iPad or not, it is certainly clear that Microsoft in a post-Windows 8 environment was in no position to pick it up. That is a shame as I think Apple created an opportunity that might have been exploited.Instead in the Windows bubble, as much as anyone might have wanted new features or improved basic capabilities, they wanted compatibility with all that had come before. Legacy applications, muscle memory, and preservation of investments were the hallmarks of Windows, not to mention the ecosystem of PC makers and Intel. Why question those attributes with a new release in 2012?There was a comfort in what a PC was already doing and refining that while leaving paradigm shifts to other devices was, well, comfortable. Many saw the PC as both irreplaceable and without a substitute. Like the IT pros who knew the Windows registry, they were comfortable with their mastery of the product even if the world was moving on.Unfortunately, what is comfortable for customers is not always so comfortable for the business. Without a dominant and thriving platform, Microsoft is like a hardware company or an enterprise-only software supplier—reliant on deep customer relationships, legacy product lock-in, pricing power, and big company scale to drive the business. Those can work for a time, and perhaps even bide time hoping to invent the next platform. IBM continues to prove this every quarter, much to the surprise of technologists who today don’t even know what IBM makes or does.Windows 8 was not one thing, and therein lies its main challenge. Windows 8 was not simply a release of Windows, some new APIs, and a new PC. Windows 8 was a paradigm—it could not be disassembled into components and still stand. If we had just built a Microsoft PC for Windows 7 that would not have changed the trajectory of the business, just as we have since seen with hardware efforts. We already saw how touch on existing desktop software didn’t deliver. Moving from Intel to ARM without new software or worse just porting existing software was running in place at best and taking focus away from worthwhile endeavors at worst.To shift the paradigm and to enable Microsoft to have assets and compete in some new way required an all-or-nothing bet. Everything we know about disruption reveals how companies do what they can to avoid those situations and try to thread the needle. I was totally guilty of aiming to avoid that.The temptation to cling, or leverage depending on perspective, to

Happy Holiday to those in the US. This is a special double issue covering the creation and launch of Microsoft Surface, an integral part of the reimagining of Windows from the chipset to the experience. To celebrate such a radical departure from Microsoft’s historic Windows and software-only strategy this post is unlocked, so please enjoy, and feel free to share. I’ve also included a good many artifacts including the plans for what would happen after Windows 8 released that were put in place. The post following this is the very last in Hardcore Software. More on what comes next after the Epilogue.As a thank you to email subscribers of all levels, this post is unlocked for all readers. Please share. Please subscribe for updates and news.Back to 106. The Missing Start MenuIn 2010, operating in complete secrecy on the newest part of Microsoft’s campus, the Studios, was a team called WDS. WDS didn’t stand for anything, but that was the point. The security protocols for the Studio B building were strengthened relative to any other in the entire engineering campus. Housed in this building was a team working on one of the only projects that, if leaked, would be a material event for Microsoft.WDS was creating the last part of the story to reimagine Windows from the chipset to the experience.When we began the project, it was the icing on the cake. After the Consumer Preview, it had become the one thing that might potentially change the trajectory of Windows 8.As Windows 7 finished and I began to consider where we stood with hardware partners, Intel, the health of the ecosystem, and competing with Apple, I reached the same conclusion the previous leader of Windows had—Windows required great hardware to meet customer needs and to compete, but there were structural constraints on the OEM business model that seemed to preclude great hardware from emerging.At the same time, the dependence on the that channel meant there was no desire at Microsoft to compete with OEMs. In 2010, the Windows business represented 54% of Microsoft’s fiscal year operating income and Office was 49%—yes you read that correctly. BillG used to talk about that amount of revenue in terms of the small percentage of it that could easily fund a competitor or alternative to Windows. The “Year of Linux” was not just a fantasy of techies but a desired alternative for the OEMs as well. So far the OEMs had not chosen to invest materially in Linux, but that could change especially with an incentive created by Microsoft’s actions.Like my predecessors, I believed Microsoft needed to build a PC.Building PCs was something BillG was always happy to leave to other people. In an interview in 1992, Bill said, “There’s a reason I’m the second-biggest computer company in the world…. The reason is, I write software, and that’s where the profit is in this business right now.” On the other hand, the legendary computer scientist and arguably father of the tablet concept, Alan Kay, once said, “People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.”Microsoft was founded on the core belief that hardware should best be left to others. In the 1970s hardware was capital intensive, required different engineering skills, had horrible margins, and carried with it all the risks and downsides that pure software businesses, like the one BillG and PaulA had pioneered, did not worry about. With a standardized operating system, the hardware business would quickly consolidate and commoditize around IBM-compatible PCs in what was first a high-margin business that soon became something of a race to the bottom in terms of margins.Microsoft’s fantastic success was built precisely on the idea of not building hardware.BillG was always more nuanced. He and PaulA believed strongly in building hardware that created opportunities for new software. Microsoft built a hardware device, the Z-80 SoftCard, to enable its software to run on the Apple ][. Early on, Microsoft created add-in cards to play sound. PaulA personally drove the creation of the PC mouse, the famous green-eyed monster. Modern Microsoft built Xbox, but also Zune and the Kin phone.Apple built great hardware and together with great software made some insanely great products.To build hardware in this context meant to build the device that customers interacted with and to build all the software and deliver it in one complete package or, in economist’s parlance, vertical integration.Mike Angiulo (MikeAng) and the ecosystem had the job of bringing diversity to the PC ecosystem, a diversity that Apple did not have. This diversity was both an enormous strength and the source of a structural weakness of the industry. PCs in any screen size or configuration one might need could always be found or even custom built covering any required performance and capacity. If you wanted something like a portable server or a ruggedized PC for a squad car or a PC to embed in 2 Tesla MRI, Windows had something for you. Apple with its carefully curated line essentially big, bigger, biggest with storage of minimum, typical, maximum across Mac were the choices. Even a typical PC maker like Dell would offer good, better, best across screen sizes and then vary the offering across home, small business, government, education, and enterprise. Within that 3 x 3 x 5 customization was possible at every step. This is the root of why Apple was able to have the best PC, but never able to command the bulk of the market.The idea of vertical integration sounds fantastic on paper but the loss of the breadth of computing Windows had to offer was also a loss for customers. It is very easy to say “build the perfect hardware” but the world also values choice. One question we struggled with was if the “consumerization” of computing would lead to less choice or not. In general, early in adopting a technology there is less choice for customers. Increased choice comes with maturity in an effort to obtain more margin and differentiate from growing competition.One bet we were making was that Windows on ARM and a device from Microsoft was the start of a new generation of hardware. It would start, much like the IBM PC 5150, with a single flagship and then over time there would be many more models bringing the diversity that was the hallmark of the PC ecosystem.That is why we never built anything as central and critical as a mainstream PC, and never had we really considered competing so directly with Microsoft’s primary stream of profits and risking alienating those partners and sending them to Linux. The Windows business was a profit engine for the company (and still is today) and that profit flows through only a half dozen major customers. Losing even one was a massive problem.Microsoft had also lost a good deal of money on hardware, right up to the $1.15 billion write-off for Xbox issues in 2007. Going as far back to the early 1990s and the original keyboard, SideWinder joystick, cordless phone, home theater remote, wireless router, and even ActiMates Barney our track record in hardware was not great. Microsoft’s hardware accessories were at best categorized as marketing expense or concept cars. It was no surprise my predecessors backed off.Like the mouse, the sound card, and perhaps Xbox, I was certain that if we were to succeed in a broad platform shift in Windows that we would need to take on the responsibility and risk of building mainstream and profitable PC devices. We tried to create the Tablet PC by creating our own prototypes and shopping them to OEMs as proofs of concept. We repeated this motion with the predecessor to small tablets called Origami, same as we did for Media Center. Each of these failed to develop into meaningful run rates as separate product lines even after the software was integrated into Windows.OEMs were not equipped to invest the capital and engineering required to compete with Apple. As an example, Apple had repurposed a massive army of thousands of aluminum milling machines to create the unibody case used in the MacBook Pro. Not only did no OEM want to spend the capital to do this, but there was also no motivation to do so. Beyond that, the idea of spending a huge amount capital up front on the first machines using a new technology until a process or supply chain could be optimized was entirely unappealing even if the capital was dedicated.The OEMs were not aiming for highly differentiated hardware and their business needs were met with plastic cases that afforded flexibility in design and components. In practice, they often felt software was more differentiating than hardware, which was somewhat counterintuitive. The aggregate gross margin achievable in a PC software load was a multiple of the margin on the entire base hardware of a PC. The latest and coolest Android tablet was a fancy one made by Samsung, with a plastic case. The rise of Android, a commodity platform, all but guaranteed more plastic, lower quality screens, swappable parts, and the resulting lower prices.The OEMs were not in a battle to take share from Apple. They were more than happy to take share from each other. Apple laptop share was vastly smaller than the next bigger OEM making Windows laptops. Each OEM would tell us they could double the size of their entire company by taking share from the other OEMs. That’s just how they viewed the opportunity. The OEMs were smart businesspeople.Thinking we needed to build hardware, then building it, was one order of magnitude of challenge. Choosing to bring a product to mass market was another. Hardware is complicated, complex, expensive, and risky—risky on the face of it and seen as risky by Microsoft’s best customers.The Surface team, organized within the Entertainment and Devices division home to keyboards and mice, finished the first release of their namesake computer. It was a Windows Vista-powered table like the ones popular in bars, pizza places, and hotel lobbies in the 1980s when they ran Frogger. The new platform

This section was the most difficult to write. At least people look back favorably on Clippy. The Windows 8 Start screen lacks any kitsch or sentimental value. It was the wrong design for the product at the wrong time and ultimately my responsibility. This is not the story of the design. There are better people to write about the specifics. This is not a story of ignoring feedback or failing to heed the market, but a story of just what happens when you’re out of degrees of freedom. This is the story of the constraints and the rationale for how we managed a situation that we saw as a quagmire. The good thing about the Start screen was everyone had an opinion. The bad thing was most of those opinions were not favorable.Subscribers, only two more scheduled posts remaining. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit hardcoresoftware.learningbyshipping.com

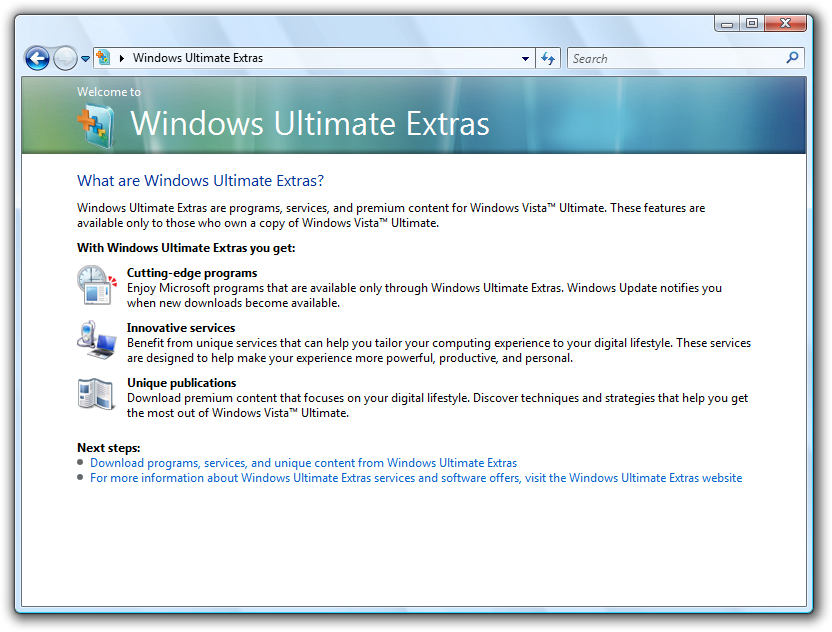

The previous section detailed the release of the Windows 8 platform, WinRT, for building Metro-style apps. In the reimagining of Windows from the chipset to the experience, we’ve covered all the major efforts. In this section, we will describe the latest in PCs that will contribute to Windows 8, which Intel called Ultrabook™ PCs We will also introduce the Windows Store where developers could distribute apps. The really big news will be the Consumer Preview or beta test for Windows 8 where millions will experience the product for the first time. It might surprise readers, just as with the Developer Preview, that the reaction to the product across many audiences was quite positive. Just how positive? And what in the world could the professional press and reviewers actually liked? And what did Apple’s Tim Cook have to say about all this?Back to 104. //build It and They Will Come (Hopefully)Following the //build conference we were feeling quite good. Not to belabor the point, but I recognize how challenging it is to take such feelings at face value given where the product ended up. In writing this and helping people experience the steps we went through at the time in sequence, my hope is that what comes to light is that we were not bonkers and in fact much of the industry was excited by Windows 8 as it emerged. Of course, there were skeptics and doubters, even haters, but as veterans of dozens of major products we’d seen this before and the volume for Windows 8 was not disproportionate. If anything, the excitement and optimism were higher. So where did things take a decidedly different direction? It was when after product emerged from the Developer Preview and a series of events including the widely distributed Consumer Preview, or beta, when millions of people would experience the product. The leadup to the Consumer Preview in March 2012 included some important steps in the process as well.New UltrabooksOn the heels of the //build conference in September 2011 Intel began kicking off an effort to reenergize the PC industry with a response to Apple, finally. Intel developed a series of specifications, financial incentives in the form of marketing and pricing actions, as well as supply chain activation to deliver on a new class of laptop. Intel called these Ultrabooks. We called them a blessing.Intel was best positioned to drive this type of advance. It was always difficult for Microsoft simply providing the operating system to dramatically alter the hardware platform, even though many thought by virtue of building Windows we held significant sway. We certainly had influence, but ultimately Windows was a wide-open platform which meant hardware to support any scenario was under PC maker control. The few times we had tried to tightly control hardware specifications, such as with Tablet PC and Media Center PC, did not go well at all. Worse, such controls angered not just PC makers but our fans as well who always wanted to build PCs on their own and experiment with hardware components.Unlike Microsoft, Intel had a unique ability to influence hardware specifications and their influence increased over time compared to Microsoft’s which waned over the years. Intel rallied the industry around Netbooks. While that was a failure, it provided a playbook that Intel could later follow. Before the Netbook, Intel almost single-handedly drove a consistent level of support for Wi-Fi with the Centrino line of chips, which bought both lower-power consumption and Wi-Fi to the standard business laptop. In these cases, and many others such as USB, SATA storage, integrated graphics, and more, Intel took on a broader role in determining components and building software drivers for Windows (and Linux) while making it easier for OEMs to adopt a complete platform.The efforts were not pure altruism. Intel would use these complete component platforms to steer OEMs to specific price points for chips as well as unit volume commitments. With those in hand, Intel could broadly advertise the platform using their massive Intel Inside advertising budget. These financial incentives were eagerly embraced by OEMs and a key part of their margin. Intel maximized its own margins as well by careful choice of CPUs in these platforms and enabling OEMs to upsell to even higher margin chips as appropriate.This dynamic is why competing with the new Apple MacBook Air starting in 2008 followed by subsequent models and then Intel-based MacBook Pros proved elusive. Conspiracy theorists would believe that Intel was slow-rolling competitive PCs just to keep Apple and Steve Jobs happy. I never saw any indication of such a dynamic. Rather, it just seemed like PC makers were basically fat and happy in their share battle with each other. They had little worry about the 3-5% of share Apple had especially because they viewed Apple laptops and their customers as high-end, expensive, and premium. The PC business was all about good price and great volume. Being a pound heavier, an inch thicker, and plastic made little difference. As Apple share among influential customers, especially in the US, increased, the urgency from Intel and PC makers changed.At the 2011 Intel Developer Forum (IDF) in Taiwan and in parallel with the //build Conference, Intel unveiled a new concept PC, the Ultrabook™. An Ultrabook wasn’t an actual PC from Intel, but a series of specifications or requirements for a PC to inherit the Ultrabook label, and thus the CPU pricing and broad co-advertising that came with it.Unlike Netbooks and Centrino, Ultrabook specifications were rather detailed and covered a broad set of criteria beyond even the components Intel provided. The tagline Intel chose was “Thin, Responsive, and Secure” which would be used quite broadly. Among the requirements to be part of this program, new PCs had to include:* Battery. A good deal of the platform effort was a new type of battery that was not yet used broadly on Windows PCs. Ultrabook PCs required non-removable Li-Poly batteries of 36-41WHr designed to fit around components and a minimum of 5 hours of runtime.* Storage and Responsiveness. While not required precisely, there was a strong recommendation to use solid state disk drives, SSDs, in Ultrabook PCs which would significantly improve performance. SSDs also made it possible to strongly recommend a wake from standby time of just 7 seconds, which for Windows PCs would be excellent at the time.* Chassis Design. For the first time, Intel specified what amounted to innovative chassis design. For laptops with 14” or larger screens, the chassis needed to be under 21mm and for smaller screens 18mm.* Screen. The Ultrabook specification included guidelines and requirements covering display selection as well, including detailed values for thickness, bezel size, viewing angles, pixel density, and power requirements. At IDF, Intel showed off displays from a number of display makers who were ready and able to supply screens.* Keyboards. Even keyboards, far from Intel’s expertise, received attention. Back-lights, spill resistant layers, key-travel and key shape were all specified in Ultrabook design. This was a significant departure for Intel and the requirements created the need for keyboard redesign for all laptops.* Sensors and devices. Intel even included recommendations for devices usually seen far off the motherboard including: 720p webcam, accelerometer, GPS, ambient light sensor and more.Intel really geared up the supply chain. This was crucially important during the huge ramp up happening with mobile phones where many suppliers were thinking of moving on from PCs. As it would turn out, Ultrabooks were the last gasp for innovative PCs.Ultrabook laptops would turn out to be the ultimate devices for the road warrior running Office. These even led to the standardization of HDMI connectors in conference rooms after decades of VGA/RGB connectors. Windows 7 had introduced the command Window+P to make it easy to switch thus ending the need for degaussing and rebooting PCs to project…mostly. The stellar work at the device and OS kernel level to reduce power consumption, improve boot time, and even the unique features for SSD storage all contributed greatly to a fantastic experience for this new form factor.Ultrabooks brought Windows hardware to the 21st century and were far more competitive with Apple laptops than we might have expected after waiting so long. In fact, Ultrabook PCs were downright cheap compared to Apple products. While most would retail for the magic number of $1,495 many could be had for the other magic number of $999. This compared to nearly twice as much for the similarly configured Apple laptops. All in all, this was a huge win for the Windows PC. Every PC laptop today owes its existence to this excellent work by Intel and the supply chain. A small benefit for tech enthusiasts and IT administrators was that the wave of Ultrabook standardization also made it possible to install Windows without requiring additional drivers to be downloaded from PC maker sites.Ultrabook PCs rapidly diffused across the ecosystem from the board room to executive teams to consultants and eventually to students. I remember a 2011 recruiting visit to MIT and Harvard and while I saw a lot (perhaps majority) of MacBooks, the PCs I saw were all newly purchased Ultrabook PCs with their sleek, un-PC-like aluminum cases.Many believed Ultrabooks would put a dent in iPad momentum. Once again, it is worth a reminder that Apple’s iPad was absolutely top of mind for the industry. The iPad was the holiday gift for 2011. Apple sold over 32 million iPads in 2011 and the tablet redefined the baseline requirements for a road warrior productivity computing. Apple, hoping to sell every Apple customer on an iPhone, MacBook, and a new iPad remained relentless in the distinct use case for iPad while also continuing to tout the iPad as the future of computing.It was this spike in demand for iPads that drove the diffic

Imagine building a computing platform that powers a generation. Now imagine taking the big step of building the replacement for that platform while the original needs to keep going for another decade or more. This is the story of unveiling the new Windows 8 platform for building modern apps, WinRT, at the first //build conference. The difficulty in telling this story is how everyone knows how the world came to view Windows 8. The developer conference of 2011 was a different story entirely. We still had to work through the big issue within the world of .NET developers and their extreme displeasure with the little we said about the Windows 8 developer story a few months earlier at the preview of the user experience. We had so much to share and were very excited as we made our way to Los Angeles.Back to 103. The End of Windows SoftwareThe iPad was out there and still had skeptics. Pundits continued to assert that tablets were not good devices for content creation. Techies saw it as a consumer toy for lightweight computing. This same thing had once been said of PCs, right up until they overtook computing. It was said of server PCs, right up until they overtook business workloads and cloud computing.Steve Jobs, at the 2010 All Things Digital D8 conference, reminded the audience that the iPad was just getting started and added, “I think we’re just scratching the surface on the kind of apps we can build for it. I think one can create a lot of content on the tablet.” By 2011, Apple was demonstrating increasing confidence in the path they had created with iPad. The iPad was already the preferred tool for the road warrior, the boardroom, and the back seat. The iPad and iPhone combined with the developer platform had become the most formidable competition Microsoft ever faced. As much as Android unit volumes concerned the Windows Phone team, there was no ignoring Apple. Some were deeply concerned about the tsunami of small Android tablets. Given what we went through with Netbooks, low quality devices, even in high volumes, concerned me less.The PC was moribund. The situation in Redmond became increasingly worrisome. This was despite our solid progress on Windows 8 and the interim Windows Phone release, Windows Phone 7.5.The chicken and egg challenge of platforms is well known. How does a platform gain traction from a standing start? Every platform faces this, but it is unusual for the established world leader to be wrestling with this problem. When I think of how the computer world had literally revolved around every utterance about Windows, it was downright depressing if not scary.The challenge the company faced was the dramatic loss of developer mindshare. Between web browsers, iPhone/iPad, and then Android, there was no room left for Microsoft. Win32 was legacy, a solid legacy, but a legacy. The latest efforts for Windows Phone seemed to have stalled at best. While there was a rhythm of press releases about app momentum for Windows Phone, the app numbers were tiny relative to Apple and Google and the app quality was low. Phone units were small too, meaning attracting developers was becoming more difficult not less.Every leadership team meeting provided another opportunity to debate the merits of using financial incentives to lure developers to the platform. And at each meeting I raised the reality of adverse selection that every competitor to Windows had learned over the past two decades. The Xbox team loved to talk about how much they spent on exclusives, but that was a walled garden world of intellectual property. In an open platform, once you’re spending money to win over developers, the least motivated developers show up with the wrong apps creating an awful cycle where paying developers attracts more of the less desirable developers building even more of the wrong apps. But not spending money seems guaranteed to lose if there’s no organic interest. This debate would become front and center with Windows 8 as we faced the same challenge.The concerns over the specifics of competing with iPad and Android tablets and how Microsoft and partners would respond occupied an increasingly concerned board. We had our plans for Windows 8, but the obvious question was could Microsoft do something sooner? In the summer of 2011, we were a couple of months from our developer conference in September and certainly less than 18 months from general availability of Windows 8. I assumed we could wait that long and knew we could not finish sooner. I also assumed there was no emergency product development that could finish something useful before then. That didn’t stop us from having a classic Microsoft hand-wringing series of meetings to attempt to cons up a plan. Time for yet another Gedankenexperiment as part of a series of meetings with some members of the board and others.We were not yet certain of the how or who of delivering ARM devices, particularly tablets, though by this point we had test hardware running and we were deep in potential designs for our own device. As a result, I was my routinely cautious self in an effort not to over-promise, especially to this group. I was, perhaps wrongly, determined not to get ahead of our own execution. Such a conservative stance was my nature but also not the norm or even appreciated. I was happy to talk about our developer conference and what was possible. The specifics required to answer when and by whom there would be a mini tablet running Windows were well ahead of where we were.I reviewed our progress on Windows 8, again. The problem seemed to be that we were not getting enough done nor was it soon enough. They were right. Who wouldn’t want more and sooner? From my vantage point, if we finished when we said we would it would be impressive and historically unique, even on the heels of Windows 7. How quickly people can forget the past. It felt like “more cowbell.”Shaving time off the schedule was discussed—it wasn’t a grounded discussion, just a wish. After that, Terry Myerson (TMyerson) and his co-leader Andy Lees (AndyLees) of the Phone team, shared the early plans for Windows Phone 8. Since Apple had made a tablet out of the iPhone, the natural question was, could we make a tablet out of Windows Phone? Of course, we could do anything (“It’s just software” as we said), but which phone and how soon?Some in attendance even asked if should do a “quick” project and build a tablet out of WP7 (or 7.5)? Could we take an Android tablet design and put Windows Phone 7 on it? Why not? Seemed so easy. None of these ideas could possibly happen. There’s no such thing as a quick project. The last quick hardware project Microsoft did was Kin, a poorly received smartphone.There wasn’t much I could do. From one perspective, Windows was suddenly the product that was holding us back and Windows Phone was the new solution to our tablet problem. Given what we were seeing in the market, Windows Phone apps, and the technical challenges of the platform, this was a ridiculous spot to land.Windows Phone 8, working with Nokia, introduced really big phones called phablets, pioneered by Samsung on Android. For a time, some analysts thought these larger phones would put an end to tablet demand because tablets were in between. Still, tablets continued to thrive for productivity and, as far as Apple was concerned, to become the future laptop. The iPad certainly thrived. It was the cheap Android tablets, the ones the Board was concerned about, that ended up on the trash heap with Netbooks.Ultimately, there was no tablet market, just an iPad market. The iPad run rate soon approximated that of consumer PC laptops. It was difficult for Microsoft to see the low-volume player as the real competitor, especially when it was Apple and the last time it was the low-volume producer it nearly died. Android was shaping up to be the Windows ecosystem on phones—high volume, low profit, endless fragility, device diversity (or randomness), and so on, but with a new OS, new OEMs, new business model, and new mobile developers who were making apps on the iPhone, though the iPhone apps always seemed a bit better.The Windows and Windows Phone teams would eventually go through a challenging period where in the middle of Windows 8, we on the Windows team learned that the Phone team had been taking snapshots of various subsystems of Windows 8 for use in the phone OS. This got the product to market but did not give us a chance to align on quality, security, reliability, and code maintenance. This wasn’t done in any coordinated or even transparent manner. Had we, Jon DeVaan and Grant George specifically, not intervened the company would have been set up for significant issues with security and reliability given we were not finished with the code and there was no process in place to manage “copies” of the code. Jon worked through a better process once the team got ahead of the issue. I had a super tense meeting with SteveB and the co-leaders of the Phone team about this lack of transparency and process and why it showed a lack of leadership, or even competence, on our part. In the new world of security, viruses, vulnerabilities, and more the company could not afford to be cavalier with source code like this seemed to demonstrate. This was all in addition to the lack of alignment on the developer platform as the Phone team made their early bet on Silverlight as previously discussed.More and sooner was a constant drumbeat throughout the Windows 8 development schedule. I was called to the carpet many times to explain where we were and why we were not finishing sooner. I was grumpy about doing that and I’m sure it showed. Schedules did not get pulled in or completed early. In the history of the company (and software), that never happened. We weren’t going to finish Windows 8 early. We would be fortunate to finish on time, mid-2012 plus two months to reach availability on new PCs.The leadup to the fall developer conference was a constant series of cris

A reasonable question to ask is “Why did Windows 8 need to create a new platform?” Not only did Microsoft have Win32, the tried-and-true real and compatible Windows platform, but the company had pioneered the .NET platform and with Windows Phone 7 extended that platform to phones with Silverlight. This post is my take on the history and how we ended up at this point. It takes us way back and shows how sometimes what emerges as a major strategic problem can trace its origins back much earlier than one might think. In the next section we will unveil the platform to developers at the //build conference.Back to 102. The ExperienceThe Windows platform and associated app ecosystem were sick. Across product executives we had a very tough time coming to grips with the abysmal situation. We definitely could not agree on when the situation turned dire or why or if it had. That meant doing something about it was going to be challenging.Some were so desperate for good news that they grabbed on to any shred of optimism. At one of the infamous Mid-Year Review (MYR) meetings during the development of Windows 7, a country general manager proudly presented their results of the annual developer survey designed to show what platform developers are coding for and the tools they use. The head of the developer segment for India said they were seeing Windows rise to the top of the chart for the most interesting and targeted platform. Windows! Immediately the room woke up from its MYR-induced stupor. Questions and comments were flying, “What outreach did you do?” “Did you start in University comp sci programs?” “How did you use financial incentives?”The optimism was misplaced. The realty was even more bleak than a benign survey outlier, a common occurrence when compensation and corporate metrics were attached to surveys. There was no surge in Windows development. Nope, it was the opposite. India had become a favorite location for companies to outsource their legacy Windows software development. We weren’t measuring an uptick. We were literally measuring the final blow to the Windows development ecosystem as companies everywhere looked to place development out of sight and out of mind. I hate to say so, but it was obvious that’s what the data showed. Microsoft itself had incented teams to transition projects to India, and not often the most strategic ones as I had learned when we had to reconstitute the Windows sustaining engineering team.Through the 1990s and the rise of Windows, BillG hosted an annual dinner for the largest and most important Windows ISVs, the CEOs and founders of leading tech companies of the era. The dinner was always a star-studded affair featuring the legends of the industry including Philippe Kahn, Jim Manzi, Ray Ozzie, Paul and George Grayson, David Fulton, Fred Gibbons, Scott Cook and perhaps 50 more. These were the leaders of the new industry each presiding over companies with hundreds of millions or billions of dollars of revenue. The companies built the tools from my earliest PC days: Borland Turbo Pascal, Lotus 1-2-3, Lotus Notes, Micrografix, FoxPro, Harvard Graphics, Quicken, and more.As Windows won, ironically the health of these companies declined. There was a natural consolidation. Many were acquired, and their products slowly faded. Microsoft had its competitive products and the rise of Office, Visual C++, Outlook, and others certainly contributed. Microsoft’s singular bet on Windows and early success on Macintosh were factors as well.It was, however, the internet and the web browser that really changed everything. The above ISVs started their companies in the 1980s on MS-DOS or in the early 1990s on Windows. Anyone starting a company, particularly in Silicon Valley, in the late 1990s started as a web company. Many startups created enterprise software, though we tend to remember the rise of Yahoo, Google, and later Facebook.A look at the top software companies in 2010 read like a list of industrial giants more than pure play software. PwC published a list, Global 100 Software Leaders, that illustrated how the industry had changed. Among the top 100, there were only three that made tools or productivity software primarily aimed at Windows or Mac: Adobe, Autodesk, and Intuit. There were even more companies that built safety, security, or management tools addressing shortcomings of the PC: McAfee, Symantec, TrendMicro, Citrix, etc. Most of the companies were either transitioning or transitioned completely to web-based interfaces running against datacenter software.The real end of the ISV dinner happened for me in 1999. The Microsoft Business Productivity Group (BPG) led by Microsoft senior vice president Bob Muglia (BobMu) announced a deal to acquire Visio Corporation for approximately $1.5 billion, Microsoft’s largest acquisition at the time. Visio was a profitable company approaching $200 million per year in revenue and nearly $30 million in net income. Bob was my manager though I didn’t know anything about the deal.The Visio Corp. founders were the fantastic team of Jeremy Jaech, Ted Johnson, and Dave Walter. Jeremy and Dave had previously co-founded Seattle-based Aldus Corporation where Ted later led the engineering for Windows PageMaker. Aldus was acquired by Adobe in 1994.Visio was a wonderful product and from the very start engineered a strong affinity to Microsoft Office, often working jointly with us on marketing, sales, and even consistency of product design. The product, an easy-to-use diagramming application, pioneered many structured drawing tools we take for granted today such as stencils of shapes, the ability to modify shape geometry, and magnetic connectors between shapes. The company was headquartered in downtown Seattle when Microsoft didn’t even have offices across the bridge.Visio was the last poster child of the old ISV world left standing to have started out as a Windows software company. It was one of the first applications developed for Windows 95, a fact that was heavily promoted. Strategically it used everything Microsoft could throw at it from Visual Basic automation to data access APIs to OLE. Ted once joked with me that they would have used Clippy if we gave them the chance.Ted, who stayed on for a bit with Microsoft and then later returned to work on Internet Explorer (TedJ), was always candid about their journey. He was wonderful to talk with and had the experiences of a founder, which was something I sought out. His view was clear that the days of being a breakthrough independent developer focused exclusively on Windows were over. It wasn’t just the browser, but also the demands of building out an enterprise sales force and having a full product line exclusively devoted to being a Windows ISV. This was even before the rise of mobile.I had a few conversations with BobMu and SteveB over whether it was a good idea for the health of the ecosystem that we participate in the ongoing consolidation. I think they heard what I was saying as a resistance to the deal because I’d end up managing the team—that wasn’t it at all and I loved the team and product. Visio was a great addition to the Office family and brought a significant amount of expertise with a great team. For me, it meant the only remaining independent and relatively horizontal Windows ISV was Adobe. Should we buy them too? Then we’d be our own ISV ecosystem. It just didn’t seem healthy.On the other hand, it was inevitable. The Windows ISV world wasn’t what it was, but why?Microsoft wasn’t standing still while this decline took place. We struggled to build both a coherent strategy and execute effectively. It wasn’t a shortage of strategy, rather it was a combination of several strategies that ended up failing to reinforce each other and ultimately weakened the overall company strategy.At the core was Microsoft’s collective response to the internet platform—the browser and the server programming model. The Windows team fully embraced the browser as the future platform, pioneering and advancing HTML along the way. In the late 1990s, Windows even redesigned the Windows desktop to integrate HTML and browser technologies on to the surface of the desktop. Still there was no bridge between Windows and the web platform. Windows simply became a place to run a browser. In Windows 7, we finally took a step of relying on Windows itself for browser features when we integrated DirectX graphics that enhanced animation, video, and overall browsing performance. That came after Microsoft ceded the dominance it earned in an earlier era, unfortunately.This entire time, the Windows desktop API—Win32—went under-nourished, so to speak. It did not really matter because anything done in a new release of Windows would be ignored by ISVs unless it also worked on older versions of Windows. Enterprise PCs continued to run older versions of Windows longer than even the 3-to-5-year upgrade cycle of Windows and PCs were lasting longer as well. No ISV was willing to invest in writing code specific to a new version of Windows for what amounted to tiny marginal gains in functionality or features. Some teams released new features that ran on the installed base of older Windows, further reducing the perceived value of a Windows upgrade. This cycle of distributing new features for the old Windows installed base increased the complexity and fragility of existing PCs by designing implementations of system-level features to work in the context of multiple versions of Windows. It was a mess. Windows had turned into a distribution vehicle for features without a coherent platform strategy.The Windows Server team faced its own API battle distinct from the client side. In the 1990s the team developed high-performance and scalable web server capabilities such as Internet Information Server. This platform handily won the enterprise market that was buying servers to host web sites along with Oracle databases, Microsoft Exchange email, and corporate file servers. T

A challenge that comes with writing down experiences occurs when writing about events that readers lived through, have strong opinions about, and feel they know the full story. My purpose here is to share what we were thinking and doing at the time, how a broad set of people reacted, and then to offer my views of the reasons leading to the results. That is a way of saying this section is going to start with what we set out to do, not where we ended.Back to 101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV]We set out to reimagine Windows, but it is interesting to ask what exactly the product is to most people. This helps us to understand the thoughts behind making a major change. We saw this in the changes to Office—we recognized the value of Office was not as many might have thought, the file formats or the old File|Edit|View|Tools|Window|Help menu structure, but rather the inherent capabilities and implementation of those capabilities. In that spirit, we looked at Windows and saw much more than the specifics of the Start menu or any particular expression of a user interface. Windows at its core proved to be a remarkably resilient operating system and our goal was to tap that resiliency to bring it new capabilities for a new world of customers.Fundamentally an operating system can be thought of as the software that allocates hardware resources, manages connectivity and devices, and defines the human to device interaction model. Beyond these technology distinctions Windows is also a culture of openness to developers and an ecosystem of partners that itself has proven resilient over time. Windows is no more one of those than a single feature or attribute above others.As both a participant in and later a contributor to the evolution of Windows, I find the transitions that the Windows product has gone through to be a case study in the “soft” part of software and in the flexibility of the product team to engineer transitions from one evolutionary stage to another. Consider just some of the transitions the Windows OS kernel or core operating system have undergone:* GUI transition. Windows itself was the product of a transition that many doubted could be made. Could an entire OS be built upon the "shaky" underpinnings of MS-DOS in the face of Macintosh? A remarkable amount of work went into the technology across the ecosystem, such support for 32-bit microprocessors, that made Windows 3.0 such a watershed product. Yet underlying that, customers could still bring forward investments in all those applications and peripherals from MS-DOS.* 32-bit transition. The transition to 32-bits was one that required a vast amount of change and brought with it the introduction of "plug and play" and the ability to run more sophisticated graphical applications and games of unrivaled qualities. The introduction of Windows 95 was a watershed moment for the whole industry. While in hindsight it looks as though it was a sure thing, many at the time proclaimed it would be technically impossible.* Internet transition. Immediately after the release of Windows 95, the conventional wisdom quickly became that Windows would be replaced by a browser. Yet few would have argued with the fact that the presence of Windows—the support for networking, the introduction of graphical web browsers on Windows, as well as the openness of the platform all contributed to the transformation of the world of information technology. In 2010 we were just starting to see how the powerful graphics of Windows could bring standards based HTML5 to life in unprecedented ways. As we will see in the next section, the programming model and API of Windows was indeed still struggling.* Server Scale. As we continued to evolve the client (workstation) OS we were using this same OS foundation to power the datacenter. With Windows Server we scaled the OS to support hundreds of computing cores and terabytes of storage. And along the way we created this OS for multiple CPU architectures driven by the demands of server computing (Alpha, MIPS, Itanium, and 64-bit). At each step most people believed that such flexibility was neither prudent nor possible.* Security and Reliability. Through the above transitions, there was an undercurrent that Windows was "aging" and that it could not transition to modern computing needs of much larger memory architectures, multi-core OS support, improved reliability, and much better security. The introduction of Windows XP was a milestone in bringing our enterprise server and workstation OS to mainstream consumers. Ironically, at the introduction of Windows XP many thought we had reached too far, and that the OS was more than people would need or could even afford to power. Throughout this transition the introduction of Windows Update enabled the OS to stay connected to customers, provide code updates, and distribute software on behalf of the ecosystem.These transitions were supported by consistently strong engineering efforts to refactor, rearchitect, and re-tune the Windows operating system. Windows also showed a broad set of efforts at the experience or user interface layer in the system as well. The various editions of including Windows Home, Windows Professional, and Windows Enterprise while often viewed as pricing and licensing efforts did in practice introduce a wide range of functionality tuned to different customer segments. Windows was able to reach up and down in complexity using the resiliency and flexibility inherent in the architecture.Yet, at the experience level Windows also struggled to achieve critical mass in several important areas even with the capabilities of the team and assets in the code. In Hardcore Software, we’ve seen the difficulties of creating tablet computers (Tablet PC), handheld computers (Windows CE), home entertainment (Windows Media Center), industrial devices (Windows Embedded), and most recently the ongoing development of smartphones (Windows Phone 7.)What is it about the experience layer that has proved so difficult for Microsoft? There could be many possible explanations. Was Microsoft too early when it should have been patient? Was Windows code simply the wrong starting point? Did we bring out good products but had inferior marketing, sales, and distribution? Some would point to one of more of these.I had my own theory and plan for trying something different.My view was that Microsoft relied too heavily on the notion of architectural layering and believed that experience could always be layered “on top” of the operating system. This computer science view drove nearly every discussion on how things should move forward. It was viewed as they key to architecting Windows for these different experiences while maintaining the shared code of the actual operating system.Microsoft systems culture (aka BillG) loved to believe that with the right architecture things in one layer could advance independent of another. I don’t think I could begin to enumerate all the times we debated issues that boiled down to me suggesting the abstractions are in the way while Bill insisted that great architecture would solve the problem. The counter was that I was failing to consider building a great architecture before addressing the problem. I was merely suggesting that we might end up spending 90% of the time on 10% of the problem.In my heart I am an “apps person” as I’ve noted many times. One thing that is conceptually different about apps from operating systems is that apps tend to be much less hardcore (or religious as some might say) about architectural layers while much more zealous about solving the customer problem even if that means breaking through well-considered abstraction layers. In an operating system there’s a general tendency to view the layers and architecture as goals the system must achieve and moving forward the layers enable advances and are deeply respected. Whereas in apps the layers and architecture tend to be the starting point while innovation and moving forward usually involve breaking those very abstractions.Each of the above attempts at expanding the experience of Windows were implemented with the explicit goal and architectural starting point of not interfering with the core of Windows. Importantly, the teams executed without organizational alignment across the Windows team or schedule. The essence of the former COSD division was to serve the main missions of Windows for desktops and for servers but generally favored the server mission for cultural and historic reasons. Whereas the Client division served the multiple experiences of Windows but did not generally prioritize experiences beyond the main client. To be clear I am not saying this was wrong at the time, rather it introduced tradeoffs that had side effects relative to other missions.This to me was the kind of decision made early in a project that is difficult to work around. The inability of the Tablet PC to fully embrace native Windows implementations or for Windows Phone to tap into the available power of the Windows operating system support for devices and connectivity were examples I’d personally experienced. As an apps person in the “two gardens” sense, the same way we needed Word and Excel to share code and align around everything from the use of the Windows registry to HTML to drawing code to user interface, we needed Windows to align around these expansions and changes to the experience.Windows was making a tradeoff at each of the junctures. There were two higher priority advances that needed to happen. First the work to transition from MS-DOS and 16-bit Windows to the full 32-bit operating system was an imperative that could not be compromised. Second, the need to continue to scale Windows up for the data center and to have a consistent client-server operating system was architecturally key. These were long term goals that were put in place and executed over at least two decades as discussed in 01

Welcome to Chapter XV! This is the final chapter of Hardcore Software. In this chapter, we are going to build and release Windows 8—reimagining Windows from the chipset to the experience. First up, the chipset. Then there will be sections on the platform and the experience. Following that, we’ll release Windows to developers and then the public. Then a surprise release of…Surface. There is a ton to cover. Many readers have lived through this. I’m definitely including a lot of detail but chose not to break things up into small posts. There are subsection breaks though.This first section covers the chipset work—moving Windows to the ARM SoC. Before diving right in, I will quickly describe the team structure and calendar of events that we will follow, both of which provide the structure to this final chapter while illustrating the scope of the effort.Back to 100. A Daring and Bold Vision This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit hardcoresoftware.learningbyshipping.com

Hardcore Software has shared the vision planning process for five releases of Office and Windows 7. Though not detailed we followed the same process for two waves of Windows Live Services as well as Internet Explorer 8 and 9. Windows 8 went through this same process, though by now as a team we had become pretty good at it. This section details the resulting Windows 8 plan, The Vision for Windows 8. As part of that, I wanted to take a bit of a journey into the alignment between Windows Phone and Windows 8 and the challenges we saw there. In doing so, I will describe things from the Windows perspective and not delve into the specifics of running the Windows Phone project, which wasn’t my responsibility. Rather, I wanted to cover the challenges of two large projects within the context of Microsoft each trying to figure out what they needed to do. Since 2010-2011 when this took place, it is the strength of Apple’s approach of starting from a reinvented desktop operating system for the iPhone and building out from there that makes the events of this time strategically interesting. As I frame events, the key questions to ask would be “Should Microsoft have waited?” and “Would it have been ok to not be in market with any phone after Windows Mobile 6.5 until 2012 or even 2013?” At least that’s how I reflect on these times. The answers are not complete as the next chapter will also cover some important aspects of this in more detail, particularly the hardware and platform elements.This section could really be a chapter and isn’t for the faint of heart. Dig in and have fun because it covers a lot of ground that took place in a relatively short time.Back to 099. The Magical iPadWe never lacked clarity in what we intended to do—reinvent Windows for a new era. That meant a new experience, a new platform for developers, a new connection to services, and, yes, new hardware. Books about reinvention (or disruption) don’t tell you that you can’t just announce such intentions to the world. It turns there is the intention to reinvent and then a plan to build it, though when you decide to share a strategy is an entirely different matter.I was old enough to have personally lived through the creation of the term Osborne effect as it pertains to pre-announcing products. In high school I programmed my father’s Osborne he bought to keep the books for the family business. We’d been using the Osborne daily since it launched and thought about buying an upgrade for the business. Then Osborne founder and CEO, Adam Osborne, pre-announced the Executive, a fancier model with more memory and a bigger screen. The only problem was it was far from being done. The prototype product was shown in 1983. Customers held off buying the original Osborne long enough that the company went bankrupt before delivering the new computer.Apple faced a similar dilemma when it first transitioned from Motorola chips to PowerPC chips. The transition was announced in 1994. While it is difficult to tease out the impact of Windows 95 from the chip transition, Apple’s share of the Mac/PC market would steadily shrink for another decade, and decline significantly in absolute unit sales, until the next chip transition to Intel.Microsoft had long been relatively immune from pre-announcing products because the overall growth of the PC market combined with the breadth of the product line dampened any pullback in a single product. The PC needed an OS even if the next one was delayed. As we saw with Longhorn/Vista, businesses still continued to buy PCs in droves. That’s why many Microsoft products seemed to be talked about long before they were released. There was an added benefit to this early sharing, or as we called it openness, which was used to generate platform momentum. With nothing to lose, Windows itself benefitted from a solid 5 years of momentum building in the early days before Windows 3.0. Back then it was all just an industry norm.In our world, the Windows business had just survived the Longhorn mess and recovered with Windows 7. We now faced an entirely new market situation. Windows itself faced structural challenges—actual alternatives in the market in the form of phones, tablets, browsers, Intel-based Macs, and soon ChromeOS. At the very least, people could just stick with Windows 7, which was fine by us, except given new alternatives most customers would not even consider buying a new or additional PC, which was very bad for us.Every bone in the Microsoft body would cry out to begin evangelizing Windows 8 as soon as we had plans. We were going to build a new platform and evangelists wanted time to articulate the strategy so developers could weigh their alternatives. But doing so would also run up against Windows Phone 7 and the platform they were evangelizing. The lack of strategic connection between Windows and Windows Phone was obvious but at the time was fraught with difficult choices, especially in the context of competing with Apple.Then there was the biggest of all problems, again something they fail to mention in books. What if the big strategic bet we planned on making ran right up against our biggest partners and customers? The whole idea of advancing Windows without our partner Intel and the major PC makers Dell, HP, and Lenovo would be heresy, plain and simple. We are talking about Wintel after all. Not only were we planning on a chipset, but we knew we would offer something radical with respect to the actual computer we’d offer customers. Double heresy.As a result, the vision we created for Windows 8 was not specific in the broad communication about the role that alternate chip platforms, SoC or system-on-a-chip, or new hardware would play in the plans. By using the term SoC we could account for both ARM, the then UK company that designed the chips used in all mobile phones and tablets, and Intel who continued to work to develop a competitive SoC with their ATOM branded chips. While the engineering was well underway, the degree of the bet still needed a bit more data and experience to decide if we could execute specifically on bringing Windows to ARM. By using SoC, if the term leaked, we could always point to Intel’s latest ATOM chips as the goal. The cost of openly defying our own ecosystem and then failing to materialize would have been immense given the state of the PC market.As far as how these alternate chips would come to market, we had not yet decided on a complete plan. Would we go the standard route which was to evangelize to the OEMs as we did with Media Center PC and later multitouch support? Would we build a first-party demonstration device and use that as the basis of evangelism as we did with Tablet PC? Or would we commit to what was either unimaginable or incredibly dumb depending on if you were our customers/partners or BillG and design, build, and sell, our own new device? The vision would be silent on this. The plans were still being made and would be resolved just a few weeks after the product vision was communicated.With the iPad announcement described in the previous section, the pressure on everyone to respond was immense. For some the rise of Android was even more worrisome, primarily because of the history of Apple being less of a real threat. Google caused more consternation because it was growing so large so quickly in an area entirely new to Microsoft. Either way, even though Microsoft was the among the first to enter the smartphone market, by 2010 our share remained in low single-digits and would never get much higher.The app revolution underway in Silicon Valley was on the iPhone. And we were missing it. I learned this firsthand sitting in the pouring rain after a wedding in San Francisco in 2010, when everyone else was using a new iPhone app to summon a limousine late at night. It was my first experience with the UberCab on-demand car service, and we couldn’t summon one on my Microsoft phone as we became drenched. The app gap was just getting started. Every day it seemed like a new company released a new app for the new iPhone platform and none of that innovation was happening on Windows. I swear it felt a bit like what IBM must have experienced when everything new was on Windows and all that was on OS/2 was what they paid to have there.Windows and Windows Phone: Alignment?The Windows Phone Team was in the midst of the significant reinvention of the phone platform, originally code-named Photon, which became Windows Phone 7 or WP7. The fall 2010 release was more than six months from the rollout of the vision for Windows 8.There were many challenges in entering, or re-entering, the smartphone business. Bootstrapping an ecosystem was chief among them. Finding the right hardware partners proved difficult in the face of competition for those same partners from Android. There was also the challenge of building a differentiated product when the high-end was so solidly iPhone while Android seemed to cover the breadth of the market. To many reading this, the market might appear analogous to the evolution of the PC market, except Android has the role of Windows and the premium niche occupied by iPhone is much larger than the eight share points Apple computers achieved.WP7 faced several software challenges simply because the core operating system was so old. Support for the latest capabilities across graphics, networking, multicore CPUs, removable storage, and devices (such as the NFC reader required on Japanese mass transit) was becoming increasingly difficult to impossible, as was enabling the product to work worldwide across languages with complex characters and input methods. A hot topic on the heels of the product release was the rollout of 4G or LTE technology, especially in Asia, and the challenges WP7 had in building support in the operating system.When it came to synergy with Windows the developer platform was the key challenge. Windows Mobile, Microsoft’s original phone OS, supported a subset of the Developer Tools stra