098. A Sea of Worry at the Consumer Electronics Show

Description

The planning for Windows 8 was moving right along. But something wasn’t right as we wrapped up Windows 7 activities at CES 2010. It was looking more and more like the plans and the way the ecosystem might rally around them would yield a watered-down result—it would be Windows and a bunch of features, or perhaps irreconcilable bloat. The way the ecosystem responded to touch support in Windows 7 concerned me. How do we avoid the risk of a plan that did too much yet not enough? Oh, and Apple scheduled a “Special Event” for January 27, 2010, just weeks after a concerning CES.

Back to 097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]

In early January 2010, I was walking around the show floor at CES the evening before opening day as I had routinely done over the years. CES 2010 was a mad rush to build a giant city of 2,500 booths only to be torn down in 4 days. This walk-through gave me a good feel for the booths and placement of demonstrations. It was just two months after the launch of Windows 7. Walking around I made a list of the key OEM booths to scope out first thing in the morning. It wasn’t scientific but visiting a booth had always been an interesting barometer and sanity check for me compared to in-person executive briefings. Later in the week I would systematically walk most of the show and write a detailed report. The next morning, along with the giant crowds, I made my way through a few dozen booths with the latest Designed for Windows 7 PCs mixed in among the onslaught of 3D-television controlled by waving your hands which garnered much of the show’s buzz.

The introduction of touch screens was a major push for Windows 7 and there was genuine excitement among the OEMs to offer touch as an option, though few, okay none, thought it would be a broadly accepted choice. Touch added significantly to the price. With two relatively small suppliers for the hardware, OEMs were not anxious to make a bet across their product line. TReller, the new CMO and CFO for Windows, made a good decision to provide strategic capital to one component maker to ensure Dell would make such a bet.

There were touch models from most every PC maker, but they were expensive—most were more than $2,500 when the typical laptop was sub-$1,000. For the OEMs this was by design. If a buyer wanted touch there was an opportunity to sell a high-end, high-margin, low-volume device. OEMs had been telling us for months that this was going to be the case, but it was still disappointing.

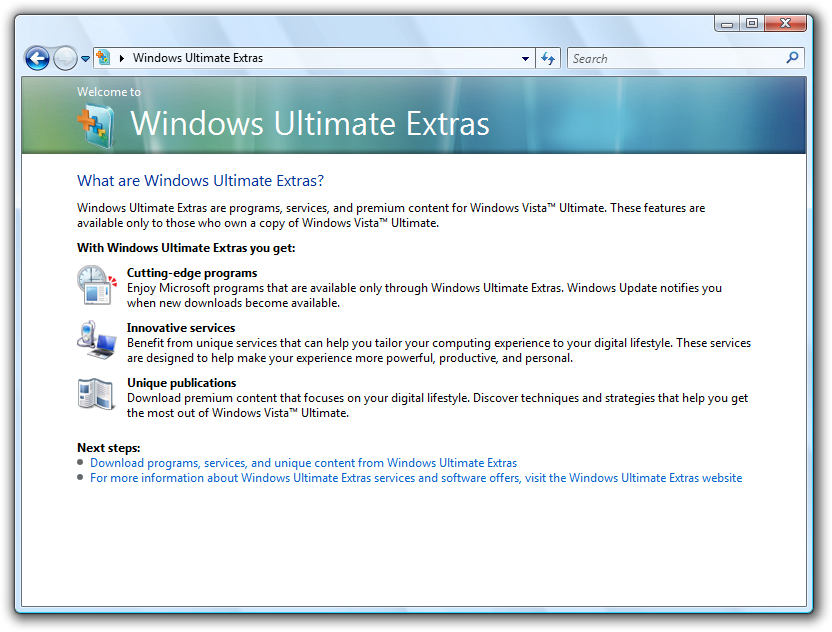

Taking advantage of Windows 7, and wholeheartedly, were a sea of Windows 7 “slates” all based on the same design from the combination of Intel and Pegatron, an ODM. These slates were essentially netbooks without keyboards. They fit the new Intel definition previously described—MID or mobile internet device. They were theoretically built as consumption-oriented companions to a PC. They were shown reading online books, listening to music, and watching movies, though not particularly high resolution or streaming given the meager hardware capabilities. All of them were relatively small and low-resolution screens. To further emphasize the Intel perspective, they also launched AppUp for Windows XP and Windows 7, a developer program and early content store designed to support rights management and in-app purchase as one might use for books and games.

The buzziest slate was from Lenovo, not a product announcement, but a prototype model kept behind glass at the private Lenovo booth located in a Venetian Hotel restaurant. The “hybrid slate” Lenovo U1 was a 11” notebook that could also be separated from the keyboard and used as both a laptop and a slate. As a laptop, the Windows 7 PC used a low-power Intel chipset, a notch slightly above a netbook. Detached as a slate, the device ran a custom operating system they named Lenovo Skylight based on Linux running on a Qualcomm Snapdragon chipset. The combination weighed almost 4lbs. The Linux tablet separated from the Windows-based keyboard PC somewhat like the saucer section of the Starship Enterprise separated from the main ship. Lenovo built software to sync some small amount of activity between the two built-in computers, such as synchronizing bookmarks and some files. Economically, two complete computers would not be the ideal way to go, bringing the cost to $1000. Strategically for Microsoft this was irritating.

Nvidia, primarily known for its graphics cards used by gamers, was always an interesting booth. Nvidia was really struggling through the recession and would finish 2010 with revenue of $3.3 billion and a loss of $60 million. As it would turn out it was also a transformative year for the company, and for one of the most legendary founders in all of the PC era, Jensen Huang. To put Nvidia in context, my very first meeting with Intel when I joined the Windows team in 2006 was about graphics, because of the Vista Capable fiasco. Intel was digging their heels in favoring integrated graphics and was not at all worried about how their capabilities were so far behind what Nvidia and ATI, another graphics card maker, were delivering, which Intel viewed as mostly about games. The rub was that AMD, Intel’s archrival, had just acquired ATI for $5.4 billion making a huge bet on discrete (non-integrated) graphics, which was what Nvidia focused on. Intel seemed to believe that the whole issue of graphics would go away as OEMs would simply accept inferior graphics from Intel because it was cheaper and easier while Intel improved integrated graphics over time, albeit slowly. A classic bundling strategy of “a tie is a win” that would turn out to be fatal for Intel and an enormous opportunity for ATI/AMD, Nvidia, and Apple. Intel could have acquired Nvidia at the time for perhaps $10-12B if that was at all possible.

In their booth Nvidia was showing off how they could add their graphics capabilities to the Intel ATOM processor and dramatically speed it up. Recall, ATOM chips struggled to even run full screen video at netbook screen resolutions. With Nvidia ION it was possible to run flawless HD video. Nvidia made this all clear in a “Netbook Nutrition Facts” label that they affixed to netbooks running Nvidia graphics. This was a shot across the bow at Intel, but Nvidia had an uphill battle to unseat bundled graphics from Intel. Nevertheless, we were acutely aware of the strong technical merits of Nvidia’s approach, Jensen’s incredible drive, and the needs of Windows customers. This will prove critically important in the next chapter as we further work on non-Intel processors.

More disappointing was how the OEMs chose to demonstrate touch capabilities in Windows 7. We provided OEMs with a suite of touch-centric applications, such as those demonstrated a year earlier—mapping, games, screen savers, and drawing, for example. We even named it Windows Touch Pack. The OEMs wanted to differentiate their touch PCs with different software and viewed the Touch Pack we provided as lame. Touch had become wildly popular in such a short time because of the iPhone, and the iPhone was a consumer device used for social interaction, consumption of media, and games.

With that frame of reference, the OEMs wanted to show scenarios that were more like an iPhone. The OEMs were going to do what they did, which was to create unique software to show off their PCs. This is just what many in the industry called crapware or, as Walt Mossberg coined in his column, craplets. To the OEMs this was a value add and important differentiation. Worst of all, there was no interest from independent software makers who had dedicated few, if any, resources to Win32 product updates, let alone updates specific to touch that was exclusive to the new Windows 7. We never intended to support Windows 7 touch on earlier versions of Windows—something developers ask of every new Windows API. This compatibility technique we often relied on but was a key contributor to Windows PC fragility and flakiness, also referred to colloquially as DLL Hell as previously described.

The overall result: Windows 7 provided no impetus for third party-developers, and we failed to muster meaningful third-party support for any new features, including touch.

What I saw was a series of new OEM apps taking a common approach. These apps could be called shells in typical Microsoft vernacular, an app for launching other apps—the Start menu, taskbar, and file explorer in Windows constitute the shell. In this case, these new shells were usually full-screen apps that had big buttons across the top to launch different programs: Browsing, Video, Music, Photos, and YouTube. These touch-friendly shells did not do much other than launch a program for each scenario, the browser, or simply a file explorer. For example, if Music was chosen then a music player, created by the OEM or chosen because of a payment for placement, would launch to play music files stored on or downloaded to a PC. The use of large touch buttons was thought to give the PC user interface a consumer feel. The browser used part of Internet Explorer but not the whole thing, just the HTML rendering component; for example, it did not include Favorites or Bookmarks usually considered part of a browser. This software, as well intentioned as it was, would fall in the crapware category. This was expected, but still disappointing.

In booths with mainstream laptops we were offered a glimpse into the changing customer views of what made a good laptop. The Windows 7 launch was just a short time ago, so most laptops had incremental updates, primarily with the new version of Windows and perhaps a slight bump in specs. Some show attendees picked up the laptops and grimaced at the weight and thickness—these machines were hardly slick. It ha

![108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue] 108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/86893731/d3f1348af12bf87ffb878bd65cadb0ba.jpg)

![101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV] 101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/75881900/3a3075fad2c894721724f8a92013a812.jpg)

![097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV] 097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/70543793/bbf82f6a403f39f35f097a445d9bf827.jpg)

![092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII] 092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/64867897/fc7d958f8115ef0d95ea5a92c0d423b4.jpg)