093. Netbook Mania

Description

The Windows team was plugging away on Windows 7. The outside world was still mired in the Vista doldrums. Then in the summer of 2007 there was a wakeup call in the announcement and shipment of a new type of computer from upstart Asus, called a Netbook, a tiny laptop running Linux and a new chip from Intel. Would that combination prove to be a competitive threat or a huge opportunity for a PC world fresh off the launch of the iPhone?

Back to 092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7

When a project like Longhorn drags on, the business is going to miss important trends. The biggest trend in computing in 2005-06 was expanding the PC to the rest of the world, something Microsoft and others called “the next billion” as the existing computing model reached approximately one billion of the world’s 6.5 billion people.

To outfit the next billion, many believed a new type of computer was needed. They were right. Many places where we would have liked to bring computers to the next billion lacked reliable electricity, air conditioning or heating, constant high-speed internet connectivity, and often had dusty environments as in Africa and much of Asia where I happened to have some of experience.

At the MIT Media Lab, Nicholas Negroponte, the lab’s founder, spearheaded a project called One Laptop Per Child, OLPC, that launched at the Davos forum in 2005. The rest of the world would come to know this as the “$100 laptop” at a time when most laptops cost about $1000 or more.

The price of $100 seemed absurd given that was less than an Intel processor and only marginally more than Windows, and that was before the rest of the hardware. Therefore, the initial designs of the OLPC would ship without commercial software from Microsoft or hardware from Intel. Instead, partners from anyone but Wintel lined up to help figure out how to build the OLPC. Almost immediately, Microsoft and Intel were blocked out of the next billion.

The resulting device, a product of some extremely fancy, perhaps fanciful, industrial design was a key part of drawing attention to what became known as the OLPC XO-1. The device featured several technical features that were aimed at solving computing needs for children in remote areas while also addressing the goal of ultra-low cost. The software was open source with a great deal of influence from historic MIT projects aimed at learning computing and programming. The effort even created a non-profit where people could go to a web site and donate the price of a device to have one distributed. The OLPC XO-1 was so cool looking that many people wanted one for their own use, right here in the US. The rollout and communications were exactly what you’d expect from the Media Lab—exciting and broadly picked up.

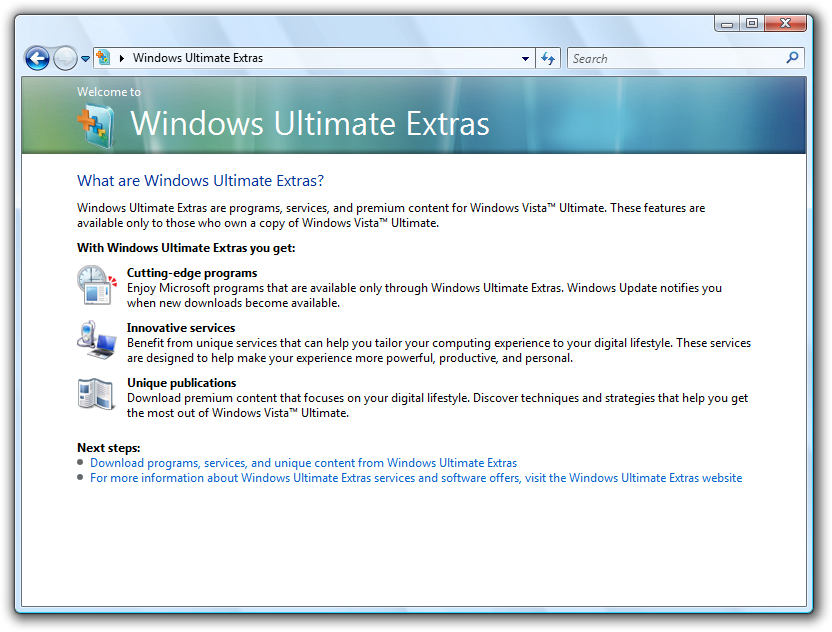

Microsoft through the Microsoft Research team and Craig Mundie (CraigMu) leading advanced technology spent a great deal of effort attempting to insert Windows into this effort. The company made progress but at the expense of causing some well-known members of the OLPC project to resign once it became clear that proprietary software was involved. Microsoft for its part would embark on the creation of a version of Windows that was ultra-low cost and stripped of many features as well, called Windows Starter Edition.

If there’s a theme in this work, both from Microsoft and MIT, it is that the core idea was that to bring computing to the next billion, products would need to cost less out of necessity and therefore they would need to do less and be less powerful. Often in the process of doing this the products would also go through transformation to make them easier to use, because apparently that is something required too. This is a fundamental mistake made time and again when addressing what the financial and economic world call emerging markets. Individuals in emerging markets do not want cheap, under-powered, or worse products. They certainly do not need products that are dumbed down. In technology, there is really no reason for that as products do get less expensive over time. Yet in the immediate term companies get stuck with their existing price structures and economics. And people in emerging markets are not less smart, they simply do not have access to the money for expensive products. I saw this dozens of times visiting the internet cafes in the most rural and economically disadvantaged parts of the world where students had no problems at all using a PC connected to the internet.

Microsoft would really get stuck in China where the limiting factor wasn’t hardware. People were buying huge numbers of PC components and simply assembling their own desktops that were on par with anything available from Dell or HP. They weren’t running Linux or Open Office, they were just pirating Windows and Office. The Windows team (I was still in Office) created a whole group to strip down Windows XP and add a shell to make it “easier” for emerging markets, again a dumbed down product. These changes to software were as much as way to make products favorable to the new markets as they were to make the product unfavorable to existing customers. Eventually, Microsoft came up with a plan to offer Windows plus Office to emerging markets, and China, governments for a very low price, so long as the computers were purchased by the government. At $3 per license this sounds like an incredible deal, but in all honesty was not that different from prices in many developed markets.

Still, the idea that the next billion required much lower priced computers, and somehow the rest of the world did not, would not go away. The need to serve this market drove the next wave of innovation from Microsoft and Intel, much more so than serving existing markets.

As Intel was mostly left out of the OLPC project, at the Intel Developer Forum in Fall 2007 they announced a new line of microprocessors with at least some emphasis on making lower cost computers for an expanded market. Intel demonstrated this processor in what is called a reference design, a PC made by Intel as a way to influence their customers to build similar PCs. The Classmate PC was a pretty cool looking laptop somewhat influenced by the Apple iBook, which brought the rounded edges, colors, and translucency of the iMac to a laptop form factor. Some would say the iBook itself owed its design lineage to the Apple eMate, based on the Newton, and sold to education markets in the 1990s. As a reference design, the PC shown could support a variety of screen sizes, storage capacities, and more, so long as it ran a new Intel low-power chip.

Also showing off the new chip in the 2007 Intel Developer Forum was the Asus Eee PC—that’s a lot of e’s, which stood for “Easy to learn, Easy to work, Easy to play” according to the box. The Eee PC was the first Netbook. It was also one of the smallest computers on the market. While there were many previous attempts at super small computers, such as the Sony PictureBook and Toshiba Libretto, there were years earlier and premium priced. This form factor and price were unique at the time. The first Eee PC 701 had the most minimal hardware specifications in any PC around and ran customized Linux and OpenOffice. It also had several games and entertainment apps.

The laptop was physically tiny as was the keyboard at 8.9 x 6.5 x 1.4 inches and under 2 pounds. It had a 7-inch display running at 800x480 pixels. For storage the Eee PC had only 4 GB of solid-state disk (like an iPod) and just 512MB of RAM. The price was $399 when it finally made it to the US, though the initial reports were it would cost $189-$299. It is worth noting that the same Intel chip was also available at retail stores in a laptop with a 14” screen, 80GB drive, a DVD drive, and 2GB RAM for about the same price. This reality would not distract from the cool factor or that it fit in any messenger-style bag.

The software load was kind of a mess, at least I thought so. The hardware, however, caught the attention of tech enthusiasts who were quick to turn the Eee PC into a tuner platform, looking to modify and replace components. Soon, modders were replacing the storage or adding more memory. There were web sites popping up devoted to modding the Eee PC.

The device sold quite well through the holiday of 2007 and that got our attention. So did the fact that modders were doing their own work to strip down Windows XP (from 2001) and squeeze it on to a 4GB system. One such modder was Asus itself which came to us wanting to officially modify Windows XP. There were three problems. First, they wanted Windows XP to cost the same as their Linux, which was $0. Second, they wanted to remove a bunch of XP just to make room on disk. What they wanted to remove was simply anything that took up space. It was kind of a free-for-all that reminded me of what enterprise customers did to Windows 3.x and Office 4.x back in the 1990s to squeeze on to 20MB hard drives.

The third problem was significant. Windows XP was done. We were over it. It was already seven years-old and we released Vista months ago. Vista was our bet. There was definitely no way Vista could be squeezed down, first of all. Second, Vista just went through the Vista Capable mess where the basic version of Vista became tainted in market and these chipsets were good enough only for Vista Basic.

If we began selling XP again for Asus, then we would have to offer it for every Netbook. And if we offered it for Netbooks then what would stop OEMs and ultimately customers demanding it for every PC. Suddenly it was looking like a roll back of Vista, especially if we participated. We didn’t really have a choice. Either we would lose the sockets to Linux, the modders would continue to pirate XP and hundreds of thousands of com

![108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue] 108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/86893731/d3f1348af12bf87ffb878bd65cadb0ba.jpg)

![101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV] 101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/75881900/3a3075fad2c894721724f8a92013a812.jpg)

![097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV] 097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/70543793/bbf82f6a403f39f35f097a445d9bf827.jpg)

![092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII] 092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/64867897/fc7d958f8115ef0d95ea5a92c0d423b4.jpg)