091. Cleaning Up Longhorn and Vista

Description

Whenever you take on a new role you hope that you can just move forward and start work on what comes next without looking back. No job transition is really like that. In my case, even though I had spent six months “transitioning” while Windows Vista went from beta to release, and then even went to Brazil to launch Windows Vista, my brain was firmly in Windows 7. I wanted to spend little, really no, time on Windows Vista. That wasn’t entirely possible because parts of our team would be producing security and bug fixes at a high rate and continuing to work with OEMs on getting Vista to market. Then, as was inevitable, I was forced to confront the ghosts of Windows Vista and even Longhorn. In particular, there was a key aspect of Windows Vista that was heavily marketed but had no product plan and there was a tail of Longhorn technologies that needed to be brought to resolution.

Back to 090. I’m a Mac

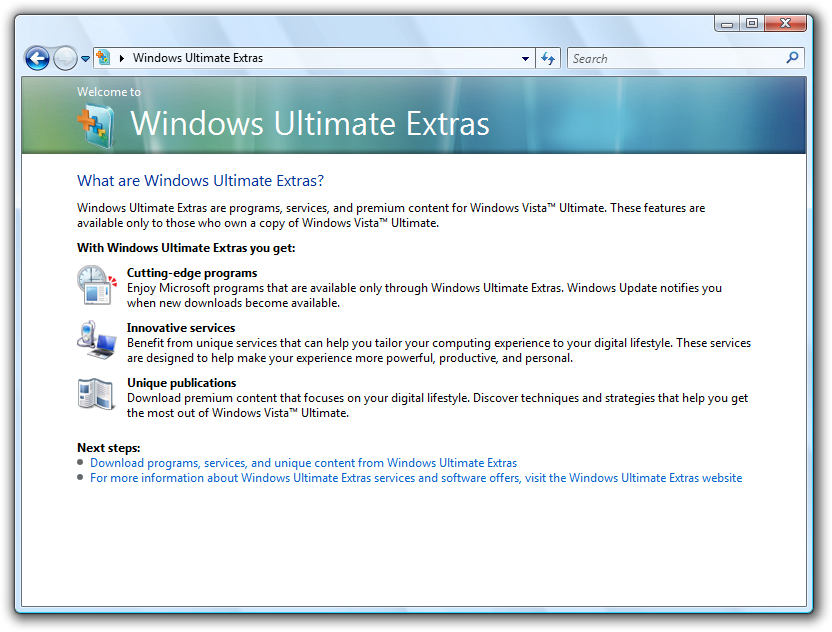

Early in my tenure, I received an escalation (!) to “fund” Windows Ultimate Extras. I had never funded anything before via a request to fund so this itself was new, and as for the escalation. . . I had only a vague idea what Ultimate Extras were, even though I had recently returned from the Windows launch event in Brazil where I was tasked with emphasizing them as part of the rollout. The request was deemed urgent by marketing, so I met with the team, even though in my head Vista was in the rearview mirror and I had transitioned to making sure servicing the release was on track, not finishing the product.

The Windows Vista Ultimate SKU was the highest priced version of Windows, aimed primarily at Windows enthusiasts and hobbyists because it had all the features of Vista, those for consumers, business, and enterprise. The idea of Ultimate Extras was to “deliver additional features for Vista via downloadable updates over time.” At launch, these were explained to customers as “cutting-edge features” and “innovative services.” The tech enthusiasts who opted for Ultimate, for a bunch of features that they probably wouldn’t need as individuals, would be rewarded with these extra features over time. The idea was like the Windows 95 Plus! product, but that was an add-on product available at retail with Windows 95.

There was a problem, though, as I would learn. There was no product plan and no development team. The Extras didn’t exist. There was an Ultimate Extras PUM, but the efforts were to be funded by using cash or somehow finding or conjuring code. This team had gotten ahead of itself. No one seemed to be aware of this and the Extras PUM didn’t seem to think this was an issue.

As the new person, this problem terrified me. We shipped and charged for the product. To my eyes the promise, or obligation if one prefers, seemed unbounded. These were in theory our favorite customers.

The team presented what amounted to a brainstorm of what they could potentially do. There were ideas for games, utilities, and so on. None of them sounded bad, but none of them sounded particularly Ultimate, and worse: None existed.

We had our first crisis. Even though this was a Vista problem, once the product released everything became my problem.

The challenge with simply finding code from somewhere, such as a vendor, licensing from a third party, or something laying around Microsoft (like from Microsoft Research), was that the journey from that code to something shippable to the tens of millions of customers running on a million different PC configurations, in 100 languages around the world, and also accessible, safe, and secure, was months of work. The more content rich the product was, in graphics or words, the longer and more difficult the process would be. I don’t know how many times this lesson needed to be learned at Microsoft but suffice it to say small teams trying to make a big difference learned it almost constantly.

And then there was the issue of doing it well. Not much of what was brainstormed at the earliest stages of this process was overly compelling.

With nothing particularly ultimate in the wings, we were poised for failure. It was a disaster.

We set out to minimize the damage to the Windows reputation and preserve the software experience on PCs. Over the following months we worked to define what would meet a reasonable bar for completing the obligation, unfortunately I mean this legally as that was clearly the best we could do. It was painful, but the prospect of spinning up new product development meant there was no chance of delivering for at least another year. The press and the big Windows fans were unrelenting in reminding me of the Extras at every encounter. If Twitter was a thing back then, every tweet of mine would have had a reply “and…now do Ultimate Extras.”

Ultimately (ha), we delivered some games, video desktops, sound schemes, and, importantly, the enterprise features of Bitlocker and language packs (the ability to run Vista in more than one language, which was a typical business feature). It was very messy. It became a symbol of a lack of a plan as well as the myth of finding and shipping code opportunistically.

Vista continued to require more management effort on my part.

In the spring of 2007 shortly after availability, a lawsuit was filed. The complaint involved the little stickers that read Windows Vista Capable placed on Windows XP computers that manufacturers were certifying (with Microsoft’s support) for upgrade to Windows Vista when it became available. This was meant to mitigate to some degree the fact that Vista missed the back to school and holiday selling seasons by assuring customers their new PC would run the much publicized Vista upgrade. The sticker on the PC only indicated it could run Windows Vista, not whether the PC also had the advanced graphics capabilities to support the new Vista user experience, Aero Glass, which was available only on Windows Vista Home Premium. It also got to the issue of whether supporting those features was a requirement or simply better if a customer had what was then a premium PC. The question was if this was confusing or too complex for customers to understand relative to buying a new PC that supported all the features of Vista.

A slew of email exhibits released in 2007 and 2008 showed the chaos and tension over the issue, especially between engineering, marketing, sales, lawyers, and the OEMs. One could imagine how each party had a different view of the meaning of the words and system requirements. I sent an email diligently describing the confusion, which became an exhibit in the case along with emails from most every exec and even former President and board member Jon Shirley (JonS) detailing their personal confusion.

The Vista Capable challenge was rooted in the type of ecosystem work we needed to get right. Intel had fallen behind on graphics capabilities while at the same time wanted to use differing graphics as part of their price waterfall. Astute technical readers would also note that Intel’s challenge with graphics was rooted deeply in their failure to achieve critical mass for mobile and the resulting attempt to repurpose their failed mobile chipsets for low-end PCs. PC makers working to have PCs available at different price points loved the idea of hardline differentiation in Windows, though they did not like the idea having to label PCs as basic, hence the XP PCs were labeled “capable.” Also worth noting was that few Windows XP PCs, especially laptops, were capable of the Home Premium experience due to the lack of graphics capabilities. When Vista released, new PCs would have stickers stating they ran Windows Vista or Windows Vista Basic, at least clarifying the single sticker that was placed on eligible Windows XP computers.

Eventually, the suit achieved class-action status, always a problem for a big company. The fact that much of the chaos ensued at the close of a hectic product cycle only contributed to this failure. My job was to support those on the team that had been part of the dialogue across PC makers, hardware makers, and the numerous marketing and sales teams internally.

The class-action status was eventually reversed, and the suit(s) reached a mutually agreeable conclusion, as they say. Still, it was a great lesson in the need to repair both the relationships and the communication of product plans with the hardware partners, not to mention to be more careful about system requirements and how features are used across Windows editions.

In addition to these examples of external issues the Vista team got ahead of itself regarding issues related to code sharing and platform capabilities that spanned multiple groups in Microsoft.

The first of these was one of the most loved modern Windows products built on top of Windows XP, Windows Media Center Edition (WMC, or sometimes MCE). In order to tap into the enthusiasm for the PC in the home and the convergence of television and PCs, long before smartphones, YouTube, Netflix, or even streaming, the Windows team created a separate product unit (rather than an integrated team) that would pioneer a new user interface, known as the 10-foot experience, and a new “shell” (always about a shell!) designed around using a PC with a remote control to show live television, home DVD discs, videos, and photos on a big screen, and also play music. This coincided with the rise in home theaters, large inexpensive disk drives capable of storing a substantial amount of video, camcorders and digital cameras, and home broadband internet connections. The product was released in 2002 and soon developed a relatively small but cultlike following. It even spawned its own online community called “Green Button,” named after the

![108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue] 108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/86893731/d3f1348af12bf87ffb878bd65cadb0ba.jpg)

![101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV] 101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/75881900/3a3075fad2c894721724f8a92013a812.jpg)

![097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV] 097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/70543793/bbf82f6a403f39f35f097a445d9bf827.jpg)

![092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII] 092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/64867897/fc7d958f8115ef0d95ea5a92c0d423b4.jpg)