107. Click In With Surface

Description

Happy Holiday to those in the US. This is a special double issue covering the creation and launch of Microsoft Surface, an integral part of the reimagining of Windows from the chipset to the experience. To celebrate such a radical departure from Microsoft’s historic Windows and software-only strategy this post is unlocked, so please enjoy, and feel free to share. I’ve also included a good many artifacts including the plans for what would happen after Windows 8 released that were put in place. The post following this is the very last in Hardcore Software. More on what comes next after the Epilogue.

As a thank you to email subscribers of all levels, this post is unlocked for all readers. Please share. Please subscribe for updates and news.

Back to 106. The Missing Start Menu

In 2010, operating in complete secrecy on the newest part of Microsoft’s campus, the Studios, was a team called WDS. WDS didn’t stand for anything, but that was the point. The security protocols for the Studio B building were strengthened relative to any other in the entire engineering campus. Housed in this building was a team working on one of the only projects that, if leaked, would be a material event for Microsoft.

WDS was creating the last part of the story to reimagine Windows from the chipset to the experience.

When we began the project, it was the icing on the cake. After the Consumer Preview, it had become the one thing that might potentially change the trajectory of Windows 8.

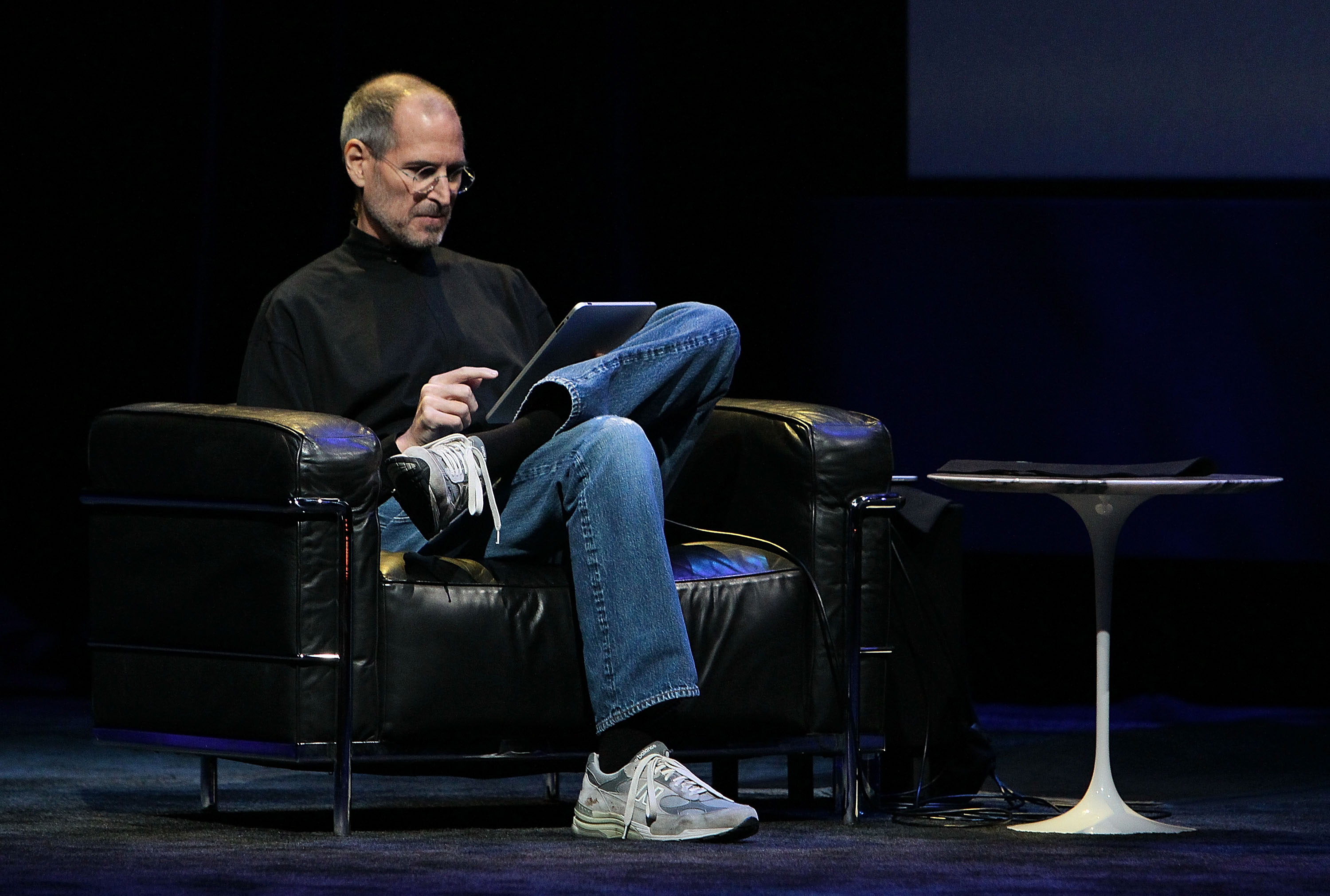

As Windows 7 finished and I began to consider where we stood with hardware partners, Intel, the health of the ecosystem, and competing with Apple, I reached the same conclusion the previous leader of Windows had—Windows required great hardware to meet customer needs and to compete, but there were structural constraints on the OEM business model that seemed to preclude great hardware from emerging.

At the same time, the dependence on the that channel meant there was no desire at Microsoft to compete with OEMs. In 2010, the Windows business represented 54% of Microsoft’s fiscal year operating income and Office was 49%—yes you read that correctly. BillG used to talk about that amount of revenue in terms of the small percentage of it that could easily fund a competitor or alternative to Windows. The “Year of Linux” was not just a fantasy of techies but a desired alternative for the OEMs as well. So far the OEMs had not chosen to invest materially in Linux, but that could change especially with an incentive created by Microsoft’s actions.

Like my predecessors, I believed Microsoft needed to build a PC.

Building PCs was something BillG was always happy to leave to other people. In an interview in 1992, Bill said, “There’s a reason I’m the second-biggest computer company in the world…. The reason is, I write software, and that’s where the profit is in this business right now.” On the other hand, the legendary computer scientist and arguably father of the tablet concept, Alan Kay, once said, “People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.”

Microsoft was founded on the core belief that hardware should best be left to others. In the 1970s hardware was capital intensive, required different engineering skills, had horrible margins, and carried with it all the risks and downsides that pure software businesses, like the one BillG and PaulA had pioneered, did not worry about. With a standardized operating system, the hardware business would quickly consolidate and commoditize around IBM-compatible PCs in what was first a high-margin business that soon became something of a race to the bottom in terms of margins.

Microsoft’s fantastic success was built precisely on the idea of not building hardware.

BillG was always more nuanced. He and PaulA believed strongly in building hardware that created opportunities for new software. Microsoft built a hardware device, the Z-80 SoftCard, to enable its software to run on the Apple ][. Early on, Microsoft created add-in cards to play sound. PaulA personally drove the creation of the PC mouse, the famous green-eyed monster. Modern Microsoft built Xbox, but also Zune and the Kin phone.

Apple built great hardware and together with great software made some insanely great products.

To build hardware in this context meant to build the device that customers interacted with and to build all the software and deliver it in one complete package or, in economist’s parlance, vertical integration.

Mike Angiulo (MikeAng) and the ecosystem had the job of bringing diversity to the PC ecosystem, a diversity that Apple did not have. This diversity was both an enormous strength and the source of a structural weakness of the industry. PCs in any screen size or configuration one might need could always be found or even custom built covering any required performance and capacity. If you wanted something like a portable server or a ruggedized PC for a squad car or a PC to embed in 2 Tesla MRI, Windows had something for you. Apple with its carefully curated line essentially big, bigger, biggest with storage of minimum, typical, maximum across Mac were the choices. Even a typical PC maker like Dell would offer good, better, best across screen sizes and then vary the offering across home, small business, government, education, and enterprise. Within that 3 x 3 x 5 customization was possible at every step. This is the root of why Apple was able to have the best PC, but never able to command the bulk of the market.

The idea of vertical integration sounds fantastic on paper but the loss of the breadth of computing Windows had to offer was also a loss for customers. It is very easy to say “build the perfect hardware” but the world also values choice. One question we struggled with was if the “consumerization” of computing would lead to less choice or not. In general, early in adopting a technology there is less choice for customers. Increased choice comes with maturity in an effort to obtain more margin and differentiate from growing competition.

One bet we were making was that Windows on ARM and a device from Microsoft was the start of a new generation of hardware. It would start, much like the IBM PC 5150, with a single flagship and then over time there would be many more models bringing the diversity that was the hallmark of the PC ecosystem.

That is why we never built anything as central and critical as a mainstream PC, and never had we really considered competing so directly with Microsoft’s primary stream of profits and risking alienating those partners and sending them to Linux. The Windows business was a profit engine for the company (and still is today) and that profit flows through only a half dozen major customers. Losing even one was a massive problem.

Microsoft had also lost a good deal of money on hardware, right up to the $1.15 billion write-off for Xbox issues in 2007. Going as far back to the early 1990s and the original keyboard, SideWinder joystick, cordless phone, home theater remote, wireless router, and even ActiMates Barney our track record in hardware was not great. Microsoft’s hardware accessories were at best categorized as marketing expense or concept cars. It was no surprise my predecessors backed off.

Like the mouse, the sound card, and perhaps Xbox, I was certain that if we were to succeed in a broad platform shift in Windows that we would need to take on the responsibility and risk of building mainstream and profitable PC devices. We tried to create the Tablet PC by creating our own prototypes and shopping them to OEMs as proofs of concept. We repeated this motion with the predecessor to small tablets called Origami, same as we did for Media Center. Each of these failed to develop into meaningful run rates as separate product lines even after the software was integrated into Windows.

OEMs were not equipped to invest the capital and engineering required to compete with Apple. As an example, Apple had repurposed a massive army of thousands of aluminum milling machines to create the unibody case used in the MacBook Pro. Not only did no OEM want to spend the capital to do this, but there was also no motivation to do so. Beyond that, the idea of spending a huge amount capital up front on the first machines using a new technology until a process or supply chain could be optimized was entirely unappealing even if the capital was dedicated.

The OEMs were not aiming for highly differentiated hardware and their business needs were met with plastic cases that afforded flexibility in design and components. In practice, they often felt software was more differentiating than hardware, which was somewhat counterintuitive. The aggregate gross margin achievable in a PC software load was a multiple of the margin on the entire base hardware of a PC. The latest and coolest Android tablet was a fancy one made by Samsung, with a plastic case. The rise of Android, a commodity platform, all but guaranteed more plastic, lower quality screens, swappable parts, and the resulting lower prices.

The OEMs were not in a battle to take share from Apple. They were more than happy to take share from each other. Apple laptop share was vastly smaller than the next bigger OEM making Windows laptops. Each OEM would tell us they could double the size of their entire company by taking share from the other OEMs. That’s just how they viewed the opportunity. The OEMs were smart businesspeople.

Thinking we needed to build hardware, then building it, was one order of magnitude of challenge. Choosing to bring a product to mass market was another. Hardware is complicated, complex, expensive, and risky—risky on the face of it and seen as risky by

![108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue] 108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/86893731/d3f1348af12bf87ffb878bd65cadb0ba.jpg)

![101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV] 101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/75881900/3a3075fad2c894721724f8a92013a812.jpg)

![097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV] 097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/70543793/bbf82f6a403f39f35f097a445d9bf827.jpg)

![092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII] 092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/64867897/fc7d958f8115ef0d95ea5a92c0d423b4.jpg)