090. I’m a Mac

Description

Advertising is much more difficult than just about everyone believes to be the case. In fact, one of the most challenging tasks for any executive at any company is to step back and not get involved in advertising. It is so easy to have opinions on ads and really randomize the process. It is easy to see why. Most of us buy stuff and therefore consume advertising. So it logically follows, we all have informed opinions, which is not really the case at all. Just like product people hate everyone having opinions on features, marketing people are loathe to deal with a cacophony of anecdotes from those on the sidelines. Nothing would test this more for all of Microsoft than Apple’s latest campaign that started in 2006. I’d already gone through enough of watching advertising people get conflicting and unreconcilable feedback to know not to stick my nose in the process.

Back to 089. Rebooting the PC Ecosystem

Hardcore Software by Steven Sinofsky is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“I’m a Mac.”

“And, I’m a PC.”

The “Get a Mac” commercials, starting in 2006, changed the competitive narrative overnight and were a painful gut punch welcoming me to Windows.

They were edgy, brutal in execution, and they skewered Windows with facts. They were well done. (Though it always bothered me that PC Guy had a vague similarity to the late and much-loved Paul Allen, Microsoft’s cofounder long focused on science and philanthropy.) Things that drove Windows fans crazy like “no viruses” on Mac were not technically true, but true in practice because, mostly, why bother writing viruses for Macs with their 6 percent share? That’s what we told ourselves. In short, these commercials were devastating.

They probably bumped right up against a line, but they effectively tapped into much of the angst and many of the realities of PC ownership and management. Our COO and others were quite frustrated by them and believed the commercials not only to be untrue, but perhaps in violation of FTC rules.

They were great advertising. Great advertising is something Apple seemed to routinely accomplish, while Microsoft found it to be an elusive skill.

For its first twenty years, Microsoft resisted broad advertising. The company routinely placed print ads in trade publications and enthusiast magazines, with an occasional national newspaper buy for launches. These ads were about software features, power, and capabilities. Rarely, if ever, did Microsoft appeal to emotions of buyers. When Microsoft appeared in the national press, it was Bill Gates as the successful technology “whiz kid” along with commentary on the growing influence and scale of the company.

With that growing influence in the early 1990s and a business need to move beyond BillG, a huge decision was made to go big in advertising. Microsoft retained Wieden+Kennedy, the Portland-based advertising agency responsible for the “Just Do It” campaign from Nike, among many era-defining successes. After much consternation about spending heavily on television advertising, Microsoft launched the “Where do you want to go today?” campaign in November 1994.

Almost immediately we learned the challenges of advertising. The subsidiaries were not enamored with the tagline. The head of Microsoft Brazil famously pushed back on the tagline, saying the translation amounted to saying, “do you want to go to the beach today?” because the answer to the question “Where do you want to go?” in Brazil was always “the beach.” The feedback poured in before we even started. It was as much about the execution as the newness of television advertising. Everyone had an opinion.

I remember vividly the many pitches and discussions about the ads. I can see the result of those meetings today as I rewatch the flagship commercial. Microsoft kept pushing “more product” and “show features” and the team from W+K would push back, describing emotions and themes. The client always wins, and it was a valuable lesson for me. Another a valuable lesson, Mike Maples (MikeMap) who had seen it all at IBM pointed out just before the formal go ahead saying something like “just remember, once you start advertising spend you can never stop. . .with the amount of money we are proposing we could hire people in every computer store to sell Windows 95 with much more emotion and information. . .” These were such wise words, as was routine for Mike. He was right. You can never stop. TV advertising spend for a big company, once started, becomes part of the baseline P&L like a tax on earnings.

The commercials were meant to show people around the world using PCs, but instead came across almost cold, dark, and ominous as many were starting to perceive Microsoft. That was version 1.0. Over the next few years, the campaign would get updates with more colors, more whimsy, and often more screenshots and pixels.

What followed was the most successful campaign the company would arguably execute, the Windows 95 launch. For the next decade, Microsoft would continue to spend heavily, hundreds of millions of dollars per year, though little of that would resonate. Coincident with the lukewarm reception to advertising would be Microsoft’s challenges in branding, naming, and in general balancing speeds and feeds with an emotional appeal to consumers. Meanwhile, our enterprise muscle continued to grow as we became leaders in articulating strategy, architecture, and business value.

In contrast, Apple had proven masterful at consumer advertising. From the original 1984 Superbowl ad through the innovative “What’s on your PowerBook?” (1992) to “Think Different” (1997-2000) and many of the most talked about advertisements of the day such as “C:\ONGRTLNS.W95” in 1995 and “Welcome, IBM. Seriously” in 1981, Apple had shown a unique ability to get the perfect message across. The only problem was that their advertising didn’t appear to work, at least as measured by sales and/or market share. The advertising world didn’t notice that small detail. We did.

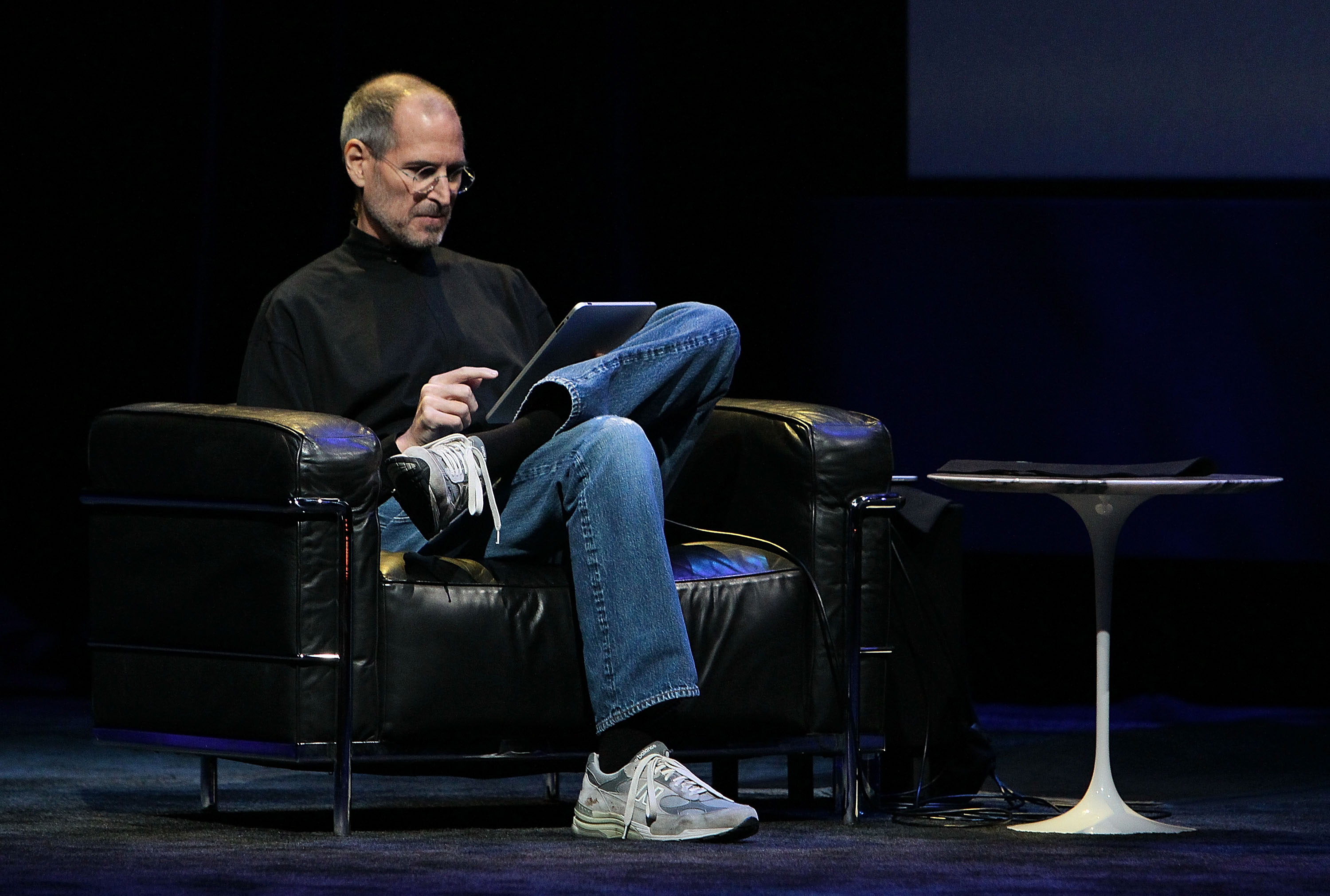

Starting in 2006 (Vista released in January 2007), Apple’s latest campaign, “Get a Mac” created an instant emotional bond with everyone struggling with their Windows PC at home or work, while also playing on all the stereotypes that existed in the Windows v. Mac battle—the nerdy businessman PC slave versus the too cool hipster Mac user.

The campaign started just as I joined Windows. I began tracking the commercials in a spreadsheet, recording the content and believability of each while highlighting those I thought particularly painful in one dimension or another. (A Wikipedia article would emerge with a complete list, emphasizing the importance of the commercials.) I found myself making the case that the commercials reflected the state of Windows as experienced in the real world. It wasn’t really all that important if Mac was better, because what resonated was the fragility of the PC. There was a defensiveness across the company, a feeling of how the “5% share Mac” could be making these claims. I managed a bit of a row with the COO who wanted to go to the FTC and complain that Apple was not telling the truth.

Windows Vista dropped the ball. Apple was there to pick it up. Not only with TV commercials and ads, but with a resurging and innovative product line, one riding on the coattails of Wintel. The irony that the commercials held up even with the transition to Intel and a theoretically level playing field only emphasized that the issue was software first and foremost, not simply a sleek aluminum case.

While the MacBook Air was a painful reminder of the consumer offerings of Windows PCs, the commercials were simply brutal when it came to Vista. There were over 50 commercials that ran from 2006-2009, starting with Apple’s transition to Intel and then right up until the release of Windows 7 when a new commercial ran on the eve of the Windows 7 launch. Perhaps the legacy of the commercials was the idea that PCs have viruses and malware and Macs do not. No “talking points” about market share or that malware targets the greatest number of potential victims or simply that the claim was false would matter. There’s no holding back, this was a brutal takedown, and it was effective. It was more effective in reputation bashing, however, than in shifting unit share.

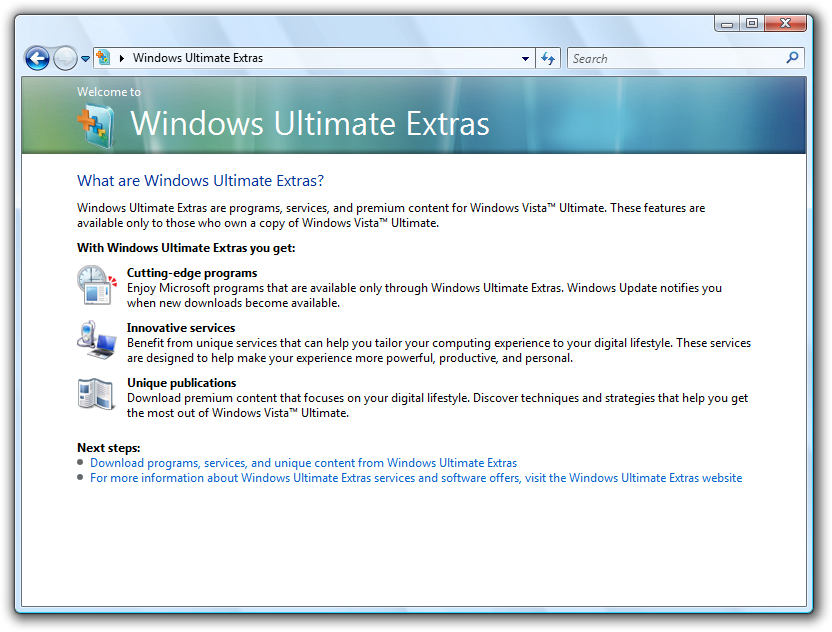

One of the most memorable ones for me was “Security” which highlighted the Windows Vista feature designed to prevent viruses and malware from sneaking on your PC, called User Account Control or UAC which had become a symbol of the annoyance of Vista—so much so our sales leaders wanted us to issue a product change to remove it. There’s some irony in that this very feature is not only implemented across Apple’s software line today, but far is more granular and invasive. That should sink in. Competitively we all seem to become what we first mock.

Something SteveB always said when faced with sales blaming the product group and the product group blaming sales for something that wasn’t working, was “we need to build what we can sell, and sell what we build.” Windows Vista was a time where we had the product and simply needed to sell what we had built, no matter what.

The marketing team (an organization peer to product development at this time) was under a great deal of pressure to turn around the perceptions of Vista and do something about the Apple commercials. It was a tall order. The OEMs were in a panic. It would require a certain level of bravery to continue to promote Vista, perhaps not unlike shipping Vista in the first place. The fact that the world was in the midst of what would become known as the Global Fi

![108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue] 108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/86893731/d3f1348af12bf87ffb878bd65cadb0ba.jpg)

![101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV] 101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/75881900/3a3075fad2c894721724f8a92013a812.jpg)

![097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV] 097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/70543793/bbf82f6a403f39f35f097a445d9bf827.jpg)

![092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII] 092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/64867897/fc7d958f8115ef0d95ea5a92c0d423b4.jpg)