Discover Conspiracy of Cartographers

Conspiracy of Cartographers

Conspiracy of Cartographers

Author: Eric J Meow

Subscribed: 3Played: 51Subscribe

Share

© Conspiracy of Cartographers

Description

Personal film photography podcast about traveling, shooting film, a bit of history, and whatever random things come up. Hosted by the former co-host of All Through a Lens.

conspiracyofcartographers.substack.com

conspiracyofcartographers.substack.com

19 Episodes

Reverse

Link to Kickstarter campaign here.Hello! And welcome back to us all! I’ve been a bit absent, haven’t I? There’s a completely reasonable and logical explanation for this. Writer’s block. I’m sure I have things to say about something, but I just don’t have the words to say them. I don’t know why.I’ll sit down to write or to come up with ideas, and there’s just nothing there. Nothing in my head. I can talk and talk about various things – I was just on the Negative Influence podcast and had a bunch of stuff to say! You should check it out. It was a great conversation! But when it’s just me and the keyboard or me and a pen, I’m rather empty.Sure, I could push through it and just say whatever b******t, but I’m not really in the business of “making content,” so when I don’t have something to say, I’d much rather just not say anything.Which means that I have something to say, doesn’t it?Well, I’ll say it.There’s a BookFor the past few years, I’ve focused a lot of my photography on small, often abandoned, cemeteries through the West and Midwest. I’ve finally decided to put together a book of some of these photos.The book is titled: Where the Plow Cannot Find Them. And right now, if you’re listening to this in mid-November of 2025, I have a Kickstarter campaign going to help release the book.While I’ve had writer’s block, I haven’t had photobook block. The thing is ready to go to print; I just need it to find an audience. And that’s where you come in. If you’re willingly listening to this, then there must be something about my photography or words that you like or can at least tolerate. Thank you for that. And fortunately, this book has both.So here I sit, still wracked with writer’s block, trying to come up with something to say that’s more than “hey, buy my book, I bet you’ll like it.I guess I can tell you a little about the book itself.This book contains 75 photographs of gravesites and 75 stories about the photographs and the people buried there. I am based out of Washington, and so many of them come from this state. Others come from Montana, Idaho, North Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, Pennsylvania, Utah, Wyoming, and Oregon. Future books will feature more and different states, but Washington will always likely have a special focus for me (if for no other reason than it’s easier).It is the culmination of thousands of miles, hundreds of cemeteries, countless photographs, and months of research. It is also (hopefully) the first volume of many.Over my years of traveling and exploring the backroads and towns of the West and Midwest, I continually came across cemeteries. Sometimes I’d stop and look around, maybe take a few pictures. But as time went on, I stayed a little longer, I looked at the names, the dates, and imagined stories. Finally, I brought along my 4x5 camera, and the cemeteries became my main subject.My interest started as something on the surface. The stones themselves, as well as their settings, were interesting. The decay, the preservation, the way they lay upon the land, and how they sometimes sank into it, all caught my eye.When I returned home and wished to share a few, I was at a loss for what to say about them. This is where the research came into things. After that, I had stories, sometimes detailed and sprawling, other times hardly anything more than names.Why Pioneers?Most people who enjoy walking, exploring, and photographing cemeteries visit the large ones, the famous ones. Cemeteries like Laurel Hill in Philadelphia or Hollywood Forever in Los Angeles get most of the visits. There’s Savannah’s Bonaventure Cemetery and Trinity Church in New York, as well. Their beauty as parks cannot be overstated.However, the cemeteries I visit have mostly been forgotten by all but locals and the few family members that remain. They are small, often unkempt, and along quiet backroads or in farmers’ fields.They contain the graves of pioneers, poor folks, and the working class. Anyone who could afford to be buried somewhere else usually was. These are the cemeteries of ghost towns and farm communities.Most were founded in the same way: A few pioneer families established homesteads on various parcels of land. Before long, a family member would die. Maybe it was the grandfather who came along. Often it was one of the children. Then, one of the farmers would give a small piece of their land to make into a cemetery. The community would grow and expand, and the cemetery would expand along with it.Then, finally, the pioneers would move on, selling their land to someone who was staying, and they’d leave their dead behind.I frequent and enjoy pioneer cemeteries over those in cities or towns. Many are abandoned and deserve a little recognition. The people who are memorialized on the stones I photograph have stories, and they deserve to be remembered.These pioneer cemeteries are often secluded and desolate. I live most of my life in a large city full of far more people than necessary. When I leave the city, I search for solitude. Few places provide more solitude than a pioneer cemetery in the middle of nowhere.The MissionI’ve spent so many hours photographing these small cemeteries. They’ve grown to be almost a second home for me. I feel comfortable in them, I feel a sort of mission, like this is my calling (if callings even exist).This writer’s block thing often comes hand-in-hand with photographer’s block (or whatever we’re calling it). I haven’t picked up a camera since August. I’m always okay with this. Creativity comes when it comes, and if I force it, then photography ends up feeling like a job rather than something I love.While I don’t miss photography when I’m not feeling creative enough to shoot something, I do miss cemeteries. I could go to one of the city cemeteries in Seattle, but there’s just no character to them. There’s no soul there. City cemeteries contain massive and beautiful stone monuments. There are thousands upon thousands of sculpted headstones, each worth its own photograph. The layout, the planning, and the landscaping of these cemeteries are all works of art. But what I long for is that small pioneer cemetery, overrun with grasses, down a lonely dirt road.There are places that I miss, that I long for, when I’m so many miles away from them. I miss my hometown, of course. I miss the coulees and sagebrush of eastern Washington, I miss the prairies of Kansas. And, maybe most of all, I miss these abandoned cemeteries.We often take photographs to remember a time or a person. We want to capture a sliver of the feeling we had in the moment. This is one of the reasons I photograph cemeteries. I love them so much - I don’t even have fancy words to describe it. It’s just a raw feeling down in my gut.I put this book together for me. I understand that a book of graves isn’t really for everyone. These hours spent among the burials might be a source of calm for me, but it might not be easily translatable.When I photograph a gravesite, my focus isn’t on making it palatable for the viewer. I’m not concerned about what will get likes on Instagram or look good as a print on a wall. My only concern is to capture how I’m feeling. This is true, of course, for every photo I take. But it’s somehow more true with cemetery photography.I know that most of the other photos I take – the ones of small towns or abandoned homes – can be and are enjoyed by a bunch of folks. Get me in front of an old house with a dark sky, and people will actually pay money for that print (this actually happened). But the grave of some child who died of smallpox in 1890? That’s not such an easy sell.But that’s where I’d rather be with my camera.The StoriesWhen I’m in the cemetery, I have almost no sense of a story. There’s just names and dates. Sometimes I can piece a little narrative together (like when a mother died in childbirth), but the details must come later.This book contains stories for each of the photos, for each of the graves, and the people memorialized on the stones. The research for these stories was necessarily rudimentary.My main source was, of course, findagrave.com. There, a user community photographs and fills in details of those buried in nearly every cemetery. Often they include death certificates, obituaries, and lists of family members.My other source is the plethora of old newspapers available on newspapers.com. Sometimes there’s not much to learn. Other times, there’s far more than I can use. Usually, it falls somewhere in the middle.When I take the photo, I never know what the story will hold. Obviously, it’s almost always a sad ending. But I do try to stay centered on their lives rather than their deaths.I’ve shared two of these stories on Substack already. In the episode titled “However It Happened, James Was Dead.” Both came out of the cemetery at Spring Ranch, Nebraska, and both stories are retold in full in this book.I also give as full an account as possible of Poker Jim, a cowboy from North Dakota. Oh, that involves a blizzard and a frozen corpse crashing a poker game. You’ll have to read it in the book; it’s a fun little tale that might even be true.And while it has some longer stories, each photograph is accompanied by a quick little tale.For instance, there’s Frankie Snyder, the child of a family originally from my home state.Frankie Snyder was born in March 1879 in Oregon. Her father, Allen Porter Snyder (AP to his friends), was, like many Snyders, born in Pennsylvania.At the age of 32, he married a woman with the delightful name of Missouri Officer. Friends called her Zude.According to Zude’s obituary, she was “born in a tent on the plains, August 13, 1845, at a place known as Ash Hollow, Wyoming,” though it was actually Three Island Crossing in Idaho. Either way, she was born on the Oregon Trail as her parents and their eight (now nine) children emigrated from Missouri. They were part of a wagon train led by Stephen Meek, and were part of the “Lost Wagon Train”.Zude and AP settled on a farm ne

I took in the Evergreen State Fair in Snohomish County, Washington, last week. I walked the midway, avoided the games, and ate too many fries and too much cotton candy. There’s always some mixed feelings swimming around in my head about the animal exhibits. I avoided the cows, but took in the sheep. Saw a bunch of horses, and rolled my eyes at the dogs. I followed half a dozen “cat” signs with arrows only to discover that the cats were somehow not there that day.Each of these stalls and pens had various awards and ribbons attached to them. Some won for showmanship, others won for driving; there were ribbons and plaques, banners and rosettes for a dizzying array of categories and classes.While the baby goats were adorable (I booped noses with one!), and the Clydesdales were intimidating and majestic, the sprawling mass of other things that were judged was a bit overstimulating.In the Arts & Crafts hall were ceramics, metalworking, various miniatures, and some diaramas. The quilts took up most of the room of the sewing hall, and they were impressive feats of bed-size, hand-sewn artistry.This sat next to your very traditional county fair food: pies, cakes, breads, and jams. There were also homemade beverages and some of the best-looking produce I’ve ever seen.Each of these items won some sort of award. Most had blue “First Place” stickers on them, while others had ribbons for “Best in Class.” Some ribbons made no sense at all to an outsider (Reserve Champion? Sweepstakes?), but it seemed like everyone did really well. Everyone got something. Good job!And finally, an entire side of the huge exhibition hall was dedicated to photography. While I don’t know much about pigs or rabbits, bell peppers or apple pies, I do know a bit of something about photography.The age groups for the photographers ranged from the youngest (ages four through nine) to senior citizens. There were also categories for Master Level and Advanced, though those designations were vague and essentially unexplainable.So how do the judges at the Evergreen State Fair judge things like Aunt Ethel’s blueberry pie? Does the rabbit with the fuzziest tail win? The cow with the best moo? And, most importantly for us, how do they judge a photograph?I don’t want to get lost in the weeds here, but technically, they use one of several systems that take into account expected standards (called the Danish Method). Sometimes they will judge on a curve (this is the American Method). There’s nothing objective or set in stone here. It’s really just the opinion of the judges. It’s a mood, a vibe.Most of this is pretty low stakes. It’s bragging rights and maybe $25. There are generally no entry fees for county fairs (except for livestock), so the risk/reward is almost nonexistent. Of course, that does make one wonder why we do it at all. The way these contests are judged is nearly random. It’s a lottery. So why do we insist upon it mattering?The Photography ExhibitionThis wasn’t my first time visiting a county fair photography contest. Here, you’ll find photos of every kind taken by folks who are just happy to have their photo up in public, where it can be seen.Like with the cows, the cakes, and quilts, these photographs had been judged, and ribbons and stickers adorned them all. You could win best in your category (and there are a lot of categories), best in your age group, best in show, and even sweepstakes (which still made no sense to me).All of this was confusing since it seemed like nearly every photograph won something, and usually, 1st place. I asked the woman overseeing the photographs, but she just explained it to me just as I explained it to you, which solved nothing for me and will now solve nothing for you. But that’s fine.Competition is nothing new. Our drive to compete for fun existed before humans, neanderthals, and even great apes playing throwing games (where you toss something and see who can toss it the farthest).I don’t think there’s anything necessarily wrong with that; whether it’s a foot race or drag racing, I get it. Sure, it can be taken too far, but seeing if your ‘69 Chevy with a 396, Fuelie heads, and a Hurst on the floor can outrun the other guy’s on the quarter mile is just good American fun. Hell, I used to watch the Amish drag racing their buggies. As humans, we just love to race stuff.And the whole thing is very simple: if you are quicker, you win. There’s really no debate; it’s purely objective. The “judging” makes sense. The same goes for most games. From football to roller derby, the team that scores the most points wins.At the fair, when I asked about the photography judges and whether they were local professionals, one of the volunteers told me that all the photos were judged “by Rick.” "Is Rick a photographer?” I asked.“Oh, he does many things, maybe he takes some pictures too,” came the reply. She then told me that Rick wasn’t here now, but he’s “probably in the pig barn, just look for the guy in the overalls.”I did visit the pig barn, but none of the overall-wearing fellows were Rick, but all of this got me thinking: Just what the hell are we doing?Incredibly Short History of Photography ContestsJudged competitions at county fairs date back to the early 1800s (and likely well before that in some shape or form). When photography became more accessible to the masses in the late 1800s, many fairs folded them into the competitions like so much Crisco into pie crust.In 1896, Charles Emsley and Dr. Lombard were the “lucky ones in the photography contest” at the Western Montana Fair in Missoula. A local paper reported that “Mr. Emsley will wear the gold medal till next fair.”But county fairs never had a monopoly on photography contests. The La Crosse Camera Company out of Wisconsin held a competition in 1895, advertising that they were giving away $1000 in gold to the winners. $200 for first place, $100 for second, $30 for third, and so on. [$1000 in 1895 is about $40,000 in today’s money.] The only catch was that you had to take the picture with one of their cameras (the La Crosse camera was a 4x5 box camera). The ad ran in papers all across the Midwest and East Coast (though a winner seems never to have been announced).Even newspapers got in on the act. In 1957, the New England Associated Press awarded its “Best in Show” prize to Charles Merrill for his picture entitled “But ‘Twas Too Late,” showing two men removing the body of a drowning victim from the ocean.Since then, it’s pretty much been the same – low stakes, low rewards (apart from the gold that possibly never existed) and essentially bragging rights.Juried Shows Are Just Photo ContestsOf course, photo contests aren’t the only photo contests. There are also juried shows, which are a little bit different, though still very much photo contests. Typically, juried shows cost money to enter, and the selection process is more rigorous. In the end, however, the awards are typically small, and it still comes down to bragging rights.Yet, juried shows are held in much higher esteem than county fairs, which is why they’re called “juried shows” and not “photography contests.” Juried shows didn’t start with photography; they actually come from the art world.Still, they seem to have been amplified by the art schools of the 1920s, and were not always received positively. In 1929, the Chicago Art Institute held a juried show whose jurors received so much ire and criticism over their curation that they considered obtaining police protection since the public was, according to the Chicago Tribune, “sufficiently upset to fall upon the offending members eye, tooth, and nail.”While the paper was almost certainly speaking in hyperbolics (after all, this was Chicago during the era of Al Capone), the jurors, as today, were acting as gatekeepers, and the artists were fed up with it.If you ask galleries that put on juried shows, they extoll such benefits to the artists as networking, credibility, and the ever-important exposure. This is the same kind of exposure that musicians rightly balk at when offered low or no-paying gigs.And to be clear, a juried show isn’t just a low-paying gig; it’s a gig the artist pays for. Each juried show has entry fees, typically around $25 to $50. That naturally doesn’t secure you a spot; it merely puts you in the running. The competition here isn’t just with the winning, but with the entering.One of the “best” bits of advice given to artists considering submission to juried shows is to avoid experimental work or work that the juror doesn’t like. Here, you are essentially trying to please a single important person rather than your typical audience (or even yourself). What the jurors want or enjoy is the only thing that matters.Gatekeeping and DemocracyWith the advent of digital photography and social media, photography was heralded as finally being democratized. This was largely true. Apart from algorithms controlling what we see, the barrier to entry, even for film photography, is incredibly low. Like in the early 1900s, anyone could pick up a camera. But now, anyone can get their work seen by dozens and even thousands of people who would otherwise never see it.This growth allows not only for novices to quickly learn their craft, but also for experimentation and innovation. These are the two things juried shows purposely dissuade, guiding the photographer to submit their “strongest” work, which here means work that will be strong enough to beat out the work of other photographers. Immediately, the vision of a strong photograph roundhouse kicking another dances through my head, and while I’m woefully overanalyzing the language here, the whole thing is a fairly absurd idea.But keep in mind that everything is subject to the whims and tastes of the juror keeping that gate. The whole process can be stifling in some pretty important ways, urging the artist to be reactive rather than creative.When photo zines started coming into their own a while back, there was some disagree

Disclaimer: Even the mere thought of the demise of Kodak makes some folks in the film community have big feelings. I’d like to state for the record (or whatever) that I don’t think Kodak is going out of business. I’m sure they’ll be around for decades to come and will never let us down. They’ll never discontinue your favorite emulsion or raise film prices. They’ll always love us and respect us, and follow us on Instagram forever. They just had a slight financial malfunction. But, uh, everything’s perfectly all right now. We’re fine. We’re all fine here, now, thank you. How are you?Last week (meaning the middle of August 2025) big news hit the film community and the Wall Street Journal: Kodak was going out of business! Well sort of not really. Kodak was apparently having yet another existential crisis.Kodak released a statement attached to an earnings report detailing their lack of earnings and highlighting their nearly half a billion dollars of debt. They wrapped it all up by declaring “these conditions raise substantial doubt about the company’s ability to continue as a going concern.”Now, this may seem like the initial rumblings that Kodak might be on its way to going out of business. But no, that’s not at ALL what they were saying, you stupid idiots, what’s wrong with you?By “these conditions raise substantial doubt about the company’s ability to continue as a going concern,” they didn’t actually mean that there was any doubt at all about their ability to continue as a going concern. In fact, it’s the opposite, obviously. And why would you think otherwise?To be clear, in the business world, no longer being a “going concern” doesn’t mean you’re immediately going out of business. It means that you’re probably going out of business in the near future. It’s night and day, okay? When a company is no longer a going concern, liquidation is almost inevitable, usually within a year’s time.While Kodak told investors and board members of their financial woes, they really didn’t want the public to think of it in such harsh terms. Also, their stocks tanked by like 20%.In classic Trump-like fashion, Kodak blamed everyone else, issuing a follow-up press release they called a “Statement Regarding Misleading Media Reports.”When I first read this real and official press release on some random guy’s Instagram post, I thought it was a parody or hoax. It was so poorly written (let alone conceived) that I figured no multi-million dollar company with a 145-year history would ever release this in any official way.I was wrong. Kodak is this company. Kodak and their decades of shockingly bad business decisions would absolutely release an official statement where they wander aimlessly between talking about themselves in the third person (as “Kodak”) and referring to some collective “we” while blaming “the media” for reporting that Kodak might go out of business after Kodak said “we will probably no longer be a going concern.” It’s baffling and just so dumb in so many ways that I’m tired of writing about it.Kodak was supposed to hold a big meeting about this on Friday, August 15th, but as of the time of this recording, they haven’t issued any details about that. Maybe by the time you’re reading this, they’ve reversed all their financial woes, re-released Kodachrome, and given every film shooter $100 just because they like us so much. Who knows? The future is impossible to predict.Anyway, now that we know for sure that Kodak will be around forever, let’s talk about life after Kodak. If Big Yellow can’t pull out of this financial tailspin, what will we, the film community, do? How will we survive without Portra and HC-110, without Tri-X and whatever they call their TMax developer?This would be the worst-case scenario. Kodak is gone. Now what?What Is Kodak?First, let’s talk about what Kodak is and, more importantly, what it isn’t. Kodak is actually named the Eastman Kodak Company. It was incorporated in 1892 and did their thing until 2012 when it filed for bankruptcy. After that, it became two companies: Eastman Kodak and Kodak Alaris.For our purposes, Eastman Kodak manufactures the film and chemicals we use. Kodak Alaris markets and sells them to us (except for motion picture film, the sales of which Eastman continues to handle).If Eastman Kodak goes out of business, Kodak Alaris goes under too. Partially because it’s all kind of one company (sort of), but also because Alaris relies on Eastman for stock. Again, I’m narrowing everything to focus specifically on the film community. In reality, it’s a bit more complex than I’m making it. A private equity firm is now involved with Alaris, and that never ends well. So even if Eastman Kodak stays afloat, we’ll have that shitty s**t to deal with eventually.So, because of this weird arrangement of Peter constantly robbing Paul to pay nobody, if Eastman Kodak goes under and all of the film they make is no longer being made, that will affect a whole slew of companies directly.Your favorite photography stores, both local and online, will take a hit. Kodak film is a pretty big chunk of their business, but probably not enough to sink them. Especially the ones who have been smart enough to diversify a bit.Companies like Cinestill, Flic Film and every other company that re-rolls and repurposes Kodak motion picture film will close. Eastman Kodak isn’t the only manufacturer of motion picture film in the world, but they’re the only ones doing color. Also, if FujiFilm is selling any color film, that will go away, too. Kodak has been making film for them for a few years now.Other companies, like Lomography, will no longer have color film. All of Lomo’s regular color film is made by Kodak. There are other options and they have other emulsions as well as their broken cameras, so I doubt they’d fully go under, but it would be pretty rough.Ilford, on the other hand, suddenly becomes the largest film manufacturer in the world, so good for them!The Whole PointFilm photography sometimes seems more about buying stuff than actually creating art. So when Kodak’s latest flirtation with oblivion came to light, we had our own little meltdown during which we said things like “What will I do without Portra?” “How will I survive without Tri-X?” “I only use HC-110! I guess I’ll switch back to digital!”Now is a good time to remember that what we create has far more to do with us than it does with the material we use to create it. It’s easy to forget that when so much of film photography is collecting gear and stocking up the film fridge, but it’s true.Of course, most of what Kodak produces can be swapped out with something else. Do you like Tri-X? You’ll be fine with Ilford HP5. Do you develop with HC-110? There’s Legacy L-110. Adore the colors of Portra or Ektachrome? Well, okay, admittedly, we’ve got a problem there. But with Ilford dipping their toes into the color pool, and with them suddenly being the largest film manufacturer in the world, it’s likely they’d jump in to fill that gap.But even that isn’t the point. The point is that we will survive the loss of our go-to emulsions should Kodak go the way of the dinosaurs. My favorite emulsion is Vericolor III. It was discontinued by Kodak in 1994. I’m doing fine. We are artists and creators, our damn job is to overcome obstacles to realize our vision, our dreams. Film is a big part of what we do, but it’s not the reason we do it. Film is not why we are artists or even photographers.We Are SmallKodak has served photographers since before photography became a thing that everyone was doing. At its height (and for a couple of generations before), every household in America and Europe had at least one camera, and that camera needed film. The film community as we know it now didn’t really exist then – it didn’t need to.Once digital became a thing, we eventually figured out that we missed film. We missed the look, the process, the ritual. A bunch of us came back. That number, however, is an incredibly minuscule fraction of the number of film shooters in the 1980s, when film was at its apex. In comparison to that, we hardly exist. If you talk to any normal person on the street, even those folks old enough to remember buying film at the drug store, nine times out of ten, they will have no idea that people are still shooting film, that film is still being produced, or that labs still exist.We are living and creating in a bubble and need to realize that. Our community is smaller than many hobbies, and yet we still expect a huge company like Kodak to somehow survive on what we can collectively spend.It’s true that during its 2012 bankruptcy, Kodak could have downsized to a smaller company to better meet the needs of its film customers, but it didn’t. On one hand, it’s understandable, in 2012, the Holga explosion was happening, but that really seemed like a fad that would fizzle out in a year or so. On the other hand, instead of downsizing, Kodak expanded into several divisions, apparently to make shitty business decisions more efficiently across various sectors.What I’m trying to say is that we are small in number and tight in community. It makes no sense at all that a company the size of Kodak would be good at serving our needs.Kodak Doesn’t CareAnd what I’m really trying to say here is something that many of you might balk at: Kodak doesn’t really care much about us. Okay, sure, there’s Tim Ryugo, but he’s one guy and not the company. When it comes to film, their main customer is Hollywood.They know that people still shoot film, of course, that’s why they still make it. It is still profitable (or whatever) for them to do so. But they’re not really a part of the community in the way that Ilford is, or the way that your local camera store is.As a community, we can survive without Kodak because in many ways, we already are. Sure, sometimes they’ll sponsor a photowalk or two in the same way that Pepsi sponsors a drag race, but apart from supplying us with some of our film and chemica

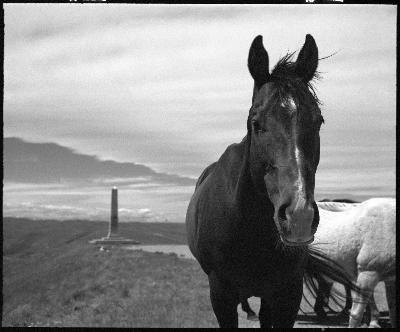

If you look through my photos, you will see pictures of abandoned buildings, of houses left empty, of roads seldom driven, of paths sometimes walked only by me. You will see endless photos of old towns, empty cars, power lines, bridges, and railroads. But you'll almost never see a photo of a person, let alone a portrait.It took me years to realize that I shied away from this. And maybe that's what it is, maybe I am shy. Too shy to ask if I could take your picture. Too shy to learn just how to make it good. Too shy to extend myself to make that connection.But part of that realization was that while I don't take pictures of people, I do take pictures of humanity, though maybe that isn’t the right word (as you’ll see soon enough). Maybe I take photos of personality.PeopleWhen someone first pointed out that I didn't take pictures of people, I almost didn't believe them. I will roam from town to town, taking many photos, talking to many people, seeing them on the streets and in their cars and in their houses, and yet, rarely have they ever appeared in my photos.All of these subjects, all of these places that I photograph, were once peopled, were once inhabited. Some still are. Nearly every photo of mine has some record of human interaction with nature.I have fallen in love with this interaction, this relationship between humans and nature. I don’t even look for it anymore, I just see it. In every place I visit, every photo I take, there it is.I used to submit some of my photos to an online group that focused upon nature photography of Washington. Their only rule was that there was to be “no hand of man” – obvious evidence of human occupation or manipulation. But almost everywhere in Washington, almost everywhere in America, you can’t find what we think of as nature without the hand of man.The trails we walk, the hills we climb, the streams we swim were all affected by this mysterious “hand of man.” Perhaps it’s not so obvious as a paved highway through a forest, but the lasting ramifications of our relationship with nature are everywhere.Nature (Animals)Our usual definition of nature is anything outside of human interference. It’s tempting to suggest that our view of nature is faulty – that maybe humans should be counted as part of nature rather than separate. This makes sense in so many ways, especially because of how we now build our houses, our cities, exiling nature to the outskirts, and well-managed parks.But in another sense, maybe it's our perception of people that is faulty. Our idea of personhood and personality is very narrow. We see ourselves in it, of course, and sometimes we extend it to our pets, which is understandable. But almost never does it cross that line, almost never does it leave our house, our property, our bubble.And yet, it shouldn't be a stretch to see other animals as people. We give names to our pets. We see the personalities in our cats and dogs. And so it shouldn't be insurmountable for us to see the animals we come into contact with in the same light. Maybe we aren't as familiar with their ways, but we could be. There's very little stopping that from happening. Maybe it’s our shyness. Maybe all of us are as shy with the animals as I am with people.I don’t take too many photos of animals, if I’m being honest. I shared a couple of stories not too long ago about photographing some cows. I’ve also photographed a bird or two, when I got the opportunity. And, of course, there are the photos of Juniper on her deathbed. It was a devastating honor to take those photos.I do wish I could take more photos of animals, but it isn't shyness that's stopping me, it is skill and maybe patience. I don't have the patience to be a wildlife photographer. Also, most of my lenses are wide. In many photos, there must be hidden animals, unseen, staring at me, wondering what I am doing with a 90 mm lens. If only they could tell me.Nature: PlantsBut why not the plants? In some narrow ways, we are familiar with seeing plants as people. We raise and talk to, and even name, flowers and ferns. There was a prayer plant who lived in my house, and his name was Greg. I didn't name him, but he came to the house with that name, and it stuck.Many of us fawn over the flowers and vegetables growing in our gardens, and we form what logic tells us is a one-way relationship with them. But somewhere inside, we do understand that there is an exchange happening. Even materially, we water them, they grow, in return, they make us happy and fill our stomachs.So why not the plants in the wild? Why not the trees, the grasses, why not the wildflowers and sage? Even in the cities, plants are more plentiful than our human neighbors. And they're often much easier to deal with.Other PeopleI don't think I've always seen plants and animals in this way, but I'm having a hard time remembering when I didn't. It's something that I simply haven't given much thought to. But when I look through my photos, I can see it’s there. I am, in a way, taking photos of people. Maybe they aren't human people. And many of them aren't animal people.But I take portraits of trees. I focus in on flowers. They are not, as we often mistake, inanimate objects. They have life in them. They cycle through birth, disease, and death the same way we do. We have much more in common with them than we do a house, or a bridge, or a car.There is a world going on around us, under our feet, above our heads, and in some ways, we are connected to it. But in most ways, I think we've neglected it. Maybe we’ve forgotten. Maybe we've never had it.When we were babies, did we really see much of a difference between our older sibling and the dog? Didn't we have a favorite tree? Didn't we have that childhood urge to run to the forest?I was fortunate enough to grow up in a small town surrounded by farmers’ fields and woods. A large creek bordered one side of town, and I’d spend entire summer days running through the trees, scrambling up hills, building forts, and catching turtles and bugs.I learned quickly that if I sat silent and still, birds and squirrels would get used to me, ignore me, and go about their normal business. There were special moments when I’d see deer creep close for a drink, eyeing me all the while. And even when the deer and the squirrels weren’t around, I discovered that I could sit by a stream and just listen to its murmuring.Our Inanimate FriendsSo really, why stop at plants and animals? Couldn't the water also be a person? It can be calm and still one day, and full of anger and violence the next. We see that in ourselves. We see that in animals. And we can see that in the rivers and streams, the ocean, especially. None of these beings is inanimate.Even the rocks, though they are still and solid, are not inanimate. It may take millennia, but they can move. Even mountains can move. There is a mountain in Washington that many geologists are starting to figure out that moved from Baja California. In fact, much of Washington state is made up of tiny islands that were in the Pacific Ocean. They've all gathered together to make the home where I live now. And yet we think the land is inanimate because our lives are too short to see its motion.Nature Is MotionAs photographers, we can show the personality of animals and plants, of water, and even mountains. And I've always found it important to do so.Many photographers who photograph nature refuse to take their pictures when the wind is blowing. They want to take a beautiful photo, with a tight focus and a wide aperture. They want a tripod and the fastest shutter speed to negate any movement. I never understood this.All of nature is in motion. All of life is in motion. Even in death, we are still moving, the bugs wriggling around in our bodies, the worms in our guts. It's all motion. There's no way to escape it. As photographers, why are we trying to deny this?When I take a photo of, for example, an abandoned house, I try to show the uniformity it has with the nature around it. I try to show how it has changed and bent to the landscape. But I also try to show that everything around it is in motion by letting the shutter linger open for a second or more. I'll wait for a breeze if there is no wind, I will watch for the grasses swaying, and the tree limbs moving, and then I will open the shutter and wait, capturing more than just a quick sliver of light. I'm capturing a moment. I'm capturing a period of time, an era.Maybe all of my photos are motion pictures, in this way. But it's my way. I've only ever done it like this. I love seeing the movement. I love being reminded of how the stream is alive, the grasses are living, the leaves in the trees are waving. The blur that is present on film represents the opposite of what most nature photographers are trying to capture.Most nature photographers take after hunters, seeing something in the forest, a flash, and firing their gun to stop it. In fact, this is where the phrase snapshot was derived. Originally, it was a hunting term.But I long for the opposite of this. I go to nature to observe it, to live in it, and, as a photographer, to bring a little of it home with me. Not as a taxidermied trophy on film, but as my memory holds that moment. I want to capture how the moment felt just as much as how the moment looked. But still, nature photographers who freeze time with no movement at all fail to do this. They fail to move me.Home and HomesThis isn’t to claim that I never take photos of solid architecture, divorced from any nature around it. I do, and I enjoy that to some lesser degree. I take photos of signs, of cars, of human-built things, like any other photographer might. And yes, you can see the humanity in those things. But they are, without a doubt, things.More importantly, they are commodities. While there might be some artistry in there, they are, in the end, made to be sold. They are products in the grossest sense of the word. Even adding what little twist of artistry with t

This episode is a bit different. First, it is audio-only (and when you listen, you’ll understand why). Second, it is fully recorded in the field on a few hikes and an overnight camping trip that would usually be a photography trip. I suggest listening with headphones.Here, I take my first camera-less trip in well over 20 years. Did I survive? What is left of me? Along the way, I talk about why I wanted to try this, why I love this part of Washington state, the importance of photography, whether I regretted not bringing the camera, and so much more. There are, of course, no film photos to share with this one. I did take two or three cell phone pics, though. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit conspiracyofcartographers.substack.com

[Before we start, I want to let you know about my new zine, Cloudless. It’s now available, and you can pick it up here.]The narrow dirt road straddled the Idaho/Washington border with late spring wheat fields, their stalks nearly to my knees, growing on either side. I stopped the car on a hill and waited for the dust to settle so that I might see the scene behind me in my rearview mirror.I stepped onto the road, grabbing my camera and checking to see again what I had loaded. The road ran through a small cut into the hill, with steep enbankments rising above on either side. I scrambled to the top of one and saw the green wheat undulating like waves on a vast and uneven ocean.The hill I was on rolled its way to a small valley and other hills rising in the middle distance. An old barn stood in the valley, its wooden walls decaying and its tin roof patched, but intact. Light clouds dotted the sky.I raised the camera, took the photo, and slid back down to the road. This entire encounter took maybe thirty seconds. I stumbled into a lovely composition, and the photo nearly took itself. I was back in the car and driving to the next picture.Just how much thought I put into this photo, I couldn’t tell you. I know a good composition when I see one. I saw one and took the photo. It’s not that I didn’t think, it’s not that I just shot. I quickly scraped together whatever experience and foreknowledge I had, saw the photo before me, and took the picture.LomographyThere is a film company called Lomography that markets its rebranded films to photographers who want a certain lo-fi look. It plays well on nostalgia, and they’ve managed to turn the memories of grandma’s photo albums into a thriving business.On each roll of film they produce, they’ve printed their slogan: Don’t Think - Just Shoot! There is something mildly philosophical about this. I understand immediately what they want us to believe they’re saying. “Don’t overthink the photograph, go with your gut, shoot it!”Of course, what they’re actually saying is “buy more film.” After all, they are a company whose priority is the bottom line. The more film we shoot, the more film we buy. And the more film we shoot without thinking, the more film we blow through like a mid-80s wedding photographer.I can’t stress enough how bad this advice is. The advice is as bad as the faith of Lomography’s argument. It is only made worse by how obvious and brazen a cover it is.And still, on this trip, I brought along a film Lomography called Potsdam. Before the rebranding, the film was made by German motion picture film manufacturer ORWO, which called it UN54. I used to buy it in bulk back in my 35mm days. The only way to acquire it now in medium format is to buy it as Potsdam from Lomography.I love how this emulsion handles shadows, how inky dark it can be. There is a contrast to this film that you can ply with a yellow filter, or even red. I would shoot this film more, and might even use it regularly if not for Lomography’s lack of quality control. But more on that later.CowsI often find myself driving through range land, where cows and sometimes sheep roam free. An awareness of this is necessary when I’m driving, and caution is always in order. A few years back, while driving near the Missouri River in Montana, I was surrounded by cows with their young bulls. One of the bulls spooked and, rather than running away from my car, ran into the front quarter panel, putting a huge dent in it.I stopped to see if he was okay - he was. And then I called my insurance company to explain that a cow had hit my car. “You hit a cow?” she asked. “No,” I replied, “other way around.”Cows are usually skittish and fearful of us. It’s no wonder the hell we put them through. Taking their photo is something that almost never happens for me. The car already frightens them, and then when a human emerges from this metal cage, it’s basically the end times.But along a Summer Road I’ve photographed before, I came across cows and heifers on both sides of the road. They were behind fences, and there were no young and frightened bulls to be seen.The older cows were immediately uneasy, but the heifers, maybe a year old, were curious. Their eyes met mine, and they stood watching me. Another walked closer to get a better look.I slowly went for my camera and began talking to them in a soft voice. I have no idea if this mattered, but it put me at ease. I walked from the road, over a small ditch, and into the grass where the barbed wire fence was strung, separating the cows from the road.They stood, just looking, though I could see the clouds of hesitation and anxiety building behind their eyes. I lifted the camera and focused. This is usually as far as I’ll get with cows. At this point, they’re taking no chances and running away, often creating a mini-stampede.This time, however, they just watched. They looked into the camera. There were three of them - two younger, one older. I was afraid that the loud click of the shutter and mirror slap of the Mamiya RB67 might scare them away, but even that hardly registered.I took several photos of the trio and another of a mother and calf, who also cooperated, though with much more apprehension.I had to work quickly. I had no idea how long my luck would hold, how long the cows would tolerate this strange event happening before them. I had to “just shoot,” worried that I might miss the opportunity. But I never stopped thinking, I never ceased calculating the odds of getting just one more photo.In the end, that wouldn’t have mattered to Lomography (whose film, Potsdam, I was shooting). I quickly finished the roll and loaded another. They don’t really care if you think or not, they just want you to shoot more. And I did. Then, with the next roll of Potsdam ready to go, I returned to the car, grateful that the cows were brave girls. The boys could certainly learn some lessons.The Worst Question EverBack in the days of the previous podcast, I interviewed dozens of photographers. Through all of that, there was one question I never asked, one question that nearly every other film photography podcast asked first: “Why do you choose to shoot film?”It’s not that it’s necessarily a bad question. It’s just that nearly every film photographer answers it the same way - some variation of: “I shoot film because it makes me slow down.”This answer, like the photographers answering, comes at the question from the aspect of a former digital photographer who thoughtlessly shot everything as quickly as they could.It’s understandable; that’s how digital photography was marketed. With film, you had 36 exposures at most before you had to change rolls. With digital, you’ve got hundreds.However, these are two different issues: one of speed and one of capacity. They’re not actually related at all.The push for faster photo-taking wasn’t invented with digital cameras. All through the 70s and 80s, film camera manufacturers pushed how quick and easy their new cameras were. From the motorized backs for medium format to the point & shoot 35mms, how quickly we could blow through frames was a huge selling point.WheatThere are small dirt roads that are rarely driven by anyone but farmers to and from their tractors parked on the edge of their fields. But I drive them. There are seldom homes along them, no businesses, rarely even barns. But here, the roads rise and fall with the land. Only slightly graded (maybe once in the springtime), these Summer Roads offer us the closest feel we’ve got to the roads of the territorial days, the days before the car.As I bounced along one, driving west with the morning sun at my back, I was again between wheat fields. The road was straight and level, though a small ridge rose beyond. In the middle of the road, as if planted on purpose, grew a small and struggling stalk of wheat. Its leaves wrinkled unshaded under the sun, yet still several spikes of grains grew in seeming defiance.It was not purposely planted here. It likely fell accidentally from a seeder and somehow managed to take root. Standing alone in the center of the road, the stalk of the plant was missed by the tires of tractors and trucks over the months it had been growing. I could have driven over it, not harming it in the slightest.Instead, I stopped. I sat there looking at the stalk, wondering how I could photograph it. I don’t know how long I considered the scene. Was it even worth it? Before very long, I grabbed my camera from the back seat and walked up to the plant. I’d probably be the only car on this road all day. I had time.Looking over this stunted stalk of wheat, I consciously mulled the decisions between color and black & white, between a wide aperture and narrow. Did I feel it should be horizontal or vertical? I know I wished for a lens wider than the 90mm. It wouldn’t be the first nor last time that thought crossed my mind.The light was perfect. The sun was high enough so that I might not cast a shadow onto the plant, but low enough to bring definition and texture to the leaves and seeds. I knew I had time, so I took it.Crouching, knees now in the dirt of the road, I took my first shot - a simple black & white picture with the wheat in focus. I decided to open the aperture and held myself steady to not miss focus. I knew the fields on either side of the road would fall to a mostly ill-defined blur, but the road and the tread from the trucks driving through before me would show. The story of just how this little plant was surviving would be told.Following the shot, I returned to the car for the color film loaded into a different holder.I walked back to my previous spot, framing it over again, but closing the aperture slightly to allow the wheat fields to come into their own. I wanted them to echo this little plant. I tried another from the same position, this time focusing at infinity. This was pointless, and I think I knew it at the time. The small stalk of wheat blurs and blends into the smeared foreground as

Did you ever have someone get really intense with you over something you said? They were insistent, and even their arguments seemed a bit more involved than just boring semantics. Maybe they were even angry. And it’s someone whose opinion you valued, so immediately, you took a step back and gave a long think to whatever you said and how you said it. Then, after quite a bit of soul-searching introspection, you concluded that you were still right and what the hell was that all about?One time I was casually talking to a fellow film photographer about how much time we all spend on film photography - “it’s our hobby,” I said, “it’s what we do.” They were really unimpressed with this. I wasn’t trying to be deep or even thought-out, but they took offense.“Photography is NOT just a hobby,” they said, using the word “just” to fully and completely separate what they did for fun from what other people do for fun. “Photography is everything! It’s our artistic outlet, our means of communicating our emotions, it’s how we see the entire world!”And that’s all true. But this photographer, like me, was not a professional. They spent far more money on photography than they saw in any returns from print sales, etc. We were pretty much on the same level of photographic intensity. It was indeed our lives, it’s what we thought of when we woke up and what we dreamed about when asleep. Every second of our day was consumed by photography.At that point, I was more than happy with thinking of photography as my hobby, and myself as an amateur photographer. It’s a thing I did in my free time, and I didn’t get paid (in the sense that if this were a business, I’d have been bankrupt years ago). And this argumentative photographer was there too.This conversation took me aback. Did I misunderstand what a hobby was? Was I not arting well enough? Was my photography lacking or inferior because I was fine with it being a hobby?What is a Hobby?At first, my suspicion was that maybe we were using two drastically different definitions of “hobby.” Wasn’t a hobby just a fun thing you did in your free time because you enjoyed it?After collecting a few opinions on the matter, I hit the dictionaries and discovered, yes, that’s basically the definition we’ve all agreed upon in the English speaking world.The entire idea of having a hobby is something that didn’t come about until fairly recently in Western history. It seems that the concept didn’t even invent itself until the 1500s when some wealthy people suddenly found themselves with nothing to do and they filled this free time with stuff that seemed like work (and actually was work to poorer people – like woodworking, needlepoint, and baking), but was actually something they did for pleasure.The word hobby comes from the “hobby horse,” – a stick with a fake horse head on it. For some reason, possibly involving Tristam Shandy, that phrase was expanded to mean leisurely pastime. Eventually, the “horse” was dropped and “hobby” remained.At first it was seen as a privilege to have a hobby. But by the 1600s, “hobby” had taken on a negative connotation. Maybe this was when the phrase muttered by every shitty boss everywhere came into being: “if you can lean, you can clean.” It is almost certainly tied to the Protestant work ethic. Hobbies were seen as play, and play was something for children. Western Civilization has been in decline since then. (I’m joking, of course, it was already well on its way.)We have much more free time today than we did in the 1600s. However, we are also living through a period where free time is valued less and less, especially in the United States.For me, photography is a hobby. It’s probably a hobby for you too, and that’s okay. I also have other hobbies. Obviously, etymology is one of them. So are music and movies. I recently got a fountain pen and I suppose I could make that a hobby if I wanted to (I probably don’t, and that’s okay too). Writing is probably second to photography and scratches many of the same itches.Is Collecting Cameras a Hobby? Is it Photography?Caught up in all of this is the strange fact that film photography actually encompasses two completely different hobbies. We have photographers and camera collectors. This is muddied even farther since the Venn diagram depicting the crossover is nearly a circle. Most film photographers have a collection of cameras, and most camera collectors are also photographers.Some of the desire to draw a line between photography and hobbies comes from this. In some ways, I get it. I really hate gear talk. When photographers start talking lenses, I basically die inside. I just can’t do it. I just don’t care.It’s not that I think it’s beneath me or not artistic enough, it just doesn’t interest me in the same way that knitters talking about different gauges of needles doesn’t interest me. That’s not my hobby.I mean, I have a bunch of cameras like most other film photographers these days, but I don’t care much about them (and yes, this is a whole other thing I need to talk about someday). They’re fun to look at, and I’m basically fine with them being there, but I’m not a gear person. When someone asks me which lens I’m using, I have to look it up. I just don’t care enough to remember.But I guess you could still call me a camera collector, or at least, a guy with a camera collection.I’m the perfect candidate to look down on those photographers whose focus is gear rather than art. And I admit, it’s really ingrained in us to feel this way. It’s difficult not to. But it’s also shitty, and it’s important that we get over ourselves. Let people find their joy just as they let us find ours. And who’s to say our joy is more joyful, more pure?Photography isn’t JUST a Hobby!When someone says “photography isn’t just a hobby,” they’re actually admitting the 17th century Protestant work ethic idea that hobbies are childish, that hobbies aren’t important is true. They’re implying what they’re doing is art and is endlessly more important.Calling your artistic pursuit a hobby doesn’t diminish what you love; instead, it recognizes that the love other people have for their pursuits is just as worthy and wonderful as yours. Calling it a hobby doesn’t lessen your skills and expertise. It doesn’t make you less of an artist. It’s just a good way to remind yourself that you’re doing this for the joy of it.The problem with saying “photography is just a hobby” is that we’re also conceding that it is a hobby, but it’s also much more. And it is! Two things can be true! Most hobbies are more than just one thing. Most hobbies involve something that sets them apart from other hobbies. There’s a lot in photography that is unique to photography, but it’s not more unique than the specifics of literally any other hobby.For me, the go-to example of a hobby is model railroading. It’s nice, pretty much everyone agrees that it’s a hobby, even model railroaders (is this because they’re not pretentious?). Model railroading involves a crazy amount of artistry, physics, research, skill, and free time. There are people even more into model railroading than we are into photography, I promise you. Pretty well anyone would agree that a good model railroad layout is a work of art, and yet they’re never counted amongst other artists. They sculpt, yet aren’t seen as sculptors. They paint, yet nobody calls them painters. They’re often pretty good photographers, too. But that’s not what they lead with. They are hobbyists and seem to understand the actual value of that word.Meanwhile, we’re over here insisting that “photography isn’t just a hobby” because we can frame a picture and push a button. Maybe we need to recalibrate our enthusiasm.The Way Out of Hobbies is DumbFilm photography came back into prominence during a strange intersection of nostalgia and recession. It came about when vinyl records started making a comeback (for some, anyway – I never stopped). Things were turning very digital very quickly, and we longed for the analog.Digital photography had completely usurped film photography, and nobody but the extreme purists and hobbyists continued to use film. Camera companies had stopped making new cameras, most emulsions were discontinued, Ebay and garage sales were stocked high with grandpa’s old gear.This allowed for a very low threshold of entry for new and returning photographers. In many ways, this was equalizing. Suddenly, you didn’t have to be a professional wedding photographer to afford a Mamiya RB67 (the greatest medium format camera ever made) and a few rolls of (likely expired) slide film.Soon, an entirely new community grew from where there was none. The old gatekeepers in their photography clubs were either ignored or ousted, as thousands of new photographers entered the hobby.Unfortunately, this happened during the rise of hustle culture, a form of workaholism where pretty much every waking minute is somehow commodified. Often, it was done out of necessity, but like with anything, most people took it too far.When it came to photography, selling prints, zines, and books had always been a thing. With the introduction of hustle culture, all of those were amped up, and things like seminars, tutorials, and even collaborations ended up seeming more scammy than useful.This led to a very straight and dark line between consumers and producers, separating film photographers from those who do it as a hobby and those who were serious enough to charge money for doing it as a hobby.We like to say that this kind of thing democratizes art. We like to think that since we don’t have to rely upon publishers and galleries like photographers used to, there are no longer gates to gatekeep.This is a fairly dumb dividing line, though. What often keeps someone from making zines or prints is simply the upfront costs or the know-how, or even the desire to do one. It’s really no great achievement to select 30 or 40 photos, put them in order, and send it off to a print shop so they can make so

“You don’t take a photograph,” a young Ansel Adams might have said, “you make it.”This is probably Adams’s most famous quote. And, it’s usually just something rattled off by your photography professor because it sounds deep and you gave them a bunch of money, and they have to say something at least a little profound-ish. And you were young and impressionable. You’d buy anything.It’s used by a thousand semi-professional photographers trying to convince their potential clients that they’re doing something different, something more thoughtful.But was Adams really trying to be profound or obtusely philosophical? Was his meaning truly the chasm of profundity we seem to believe it was? Or is this quote just photography’s “Not all who wander are lost”?Ansel Adams thought that the act of photographing something should be a process, something well-considered, crafted. And it’s hard to disagree with that.And yet, it always seems a bit cringe when I hear “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.” This could be my own hang-up, assuming that the person saying or writing it was being precious and pious. It sounds pompous and inflated with self-importance. This is because it often is.Let me get this out of the way right up front. This is a pet peeve of mine. And since it’s a pet peeve, it means that I don’t have to care about your rational opinion of this because I fully understand that my opinion may not be rational. More importantly, I’d rather scan the curliest 35mm negatives than argue with someone about this. And no, you don’t have to listen to me and my dumb opinion, but here you are.Etymology for Fun and Profit!When we say “I am making a picture,” what we’re really attempting to say is that we have given this subject, this scene, or whatever we’re photographing some thought. We’re not just taking a throw-away snapshot. I don’t think that’s how Adams meant it, but we’ll get to that soon enough.First, I want to dig into the words “take” and “make.” They rhyme, and that’s a big clue to solving this mystery of why some of us say that we “make” a photograph. And we’ll get to that later too.One of my other pet peeves is writers who begin an essay, “the dictionary defines” whatever they’re talking about. It’s lazy, it’s poor form, and I know attacking it is an easy target, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be a target.This, however, is different. We’re talking about two words that are, in the case of photography, almost interchangeable. Regardless of which one we use, we are exposing some chunk of photosensitive material to light. Both words describe the same action.Both words, however, are very different, with wildly contrasting connotations. When we “take a picture,” it’s quick and thoughtless, but when we “make a picture,” it’s full of intention and purpose.Historically, the words “take” and “make” are roughly the same age. “Take” comes from early Scandinavian, and we got “make” from one of the old Germanic languages. Both were welcomed into Old English a long time ago.The definition of “take” is pretty straightforward. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “take” means “To seize, grasp, or capture something.” The original definition generally refers to capturing a town or vessel during wartime. But all of our basic definitions for “take” are drawn from this idea.The definition for “make” is “to bring into existence by construction or elaboration.” It goes on: “To produce (a material thing) by combination of parts […] to construct, assemble, frame, fashion.” “Make” is about production, about the material produced. It’s the end result of whatever we’re doing.Even now, we can see how “take” and “make” both have their parts in what we do. We “take” or capture a picture. We “make” or produce a material print.Taketh a LikenessBut let’s go a little farther. Why did we ever say “take a picture”?While it’s impossible to know who coined the term, it was first used in relation to imagery in the early 1500s. This was 300 years before the invention of photography. In the letters of Sir Thomas Cromwell, he mentions that someone would visit and “see his daughter and also take her picture.”In this case, “take” meant “to paint” a portrait. Throughout the following centuries, we see this usage again and again.Francis Meres complained in 1597 about someone “With such trimming and setting, and smoothing and correcting, as if ye meant immediately to have your pictures taken.”Oliver Goldsmith wrote of a “limner, who travelled the country, and took likenesses for fifteen shillings a head” in 1767. [Side note: the word “likeness” meaning an image or painting, dates back to well over 1000 years.] [Also, a limner was someone who illustrated a manuscript.]When photography came around, they just continued using the same word: take.In an 1839 article about Louis Daguerre (one of the inventors of photography), an author wrote about his daguerriotypes, “Some of his last works have the force of Rembrandt's etchings. He has taken them in all weathers—I may say at all hours.”The same word, “take,” was also used in early cinematography. “The biograph people came down from New York and took moving pictures of the ten-seater [bicycle],” wrote the Denver Evening Post in 1897.To be fair, “make” did show up from time to time when talking about paintings, but it does seem to have been pretty rare, and always in the past tense, often in the distant or ancient past.What we don’t see, however, is any reference to “making a photograph” prior to Ansel Adams in 1935. This is because, I believe, it was Ansel Adams who started this in his 1935 book Making a Photograph. It was Adams who redefined the word “make,” and all joking aside, that’s commendable.But I don’t think he was using the word as we use it today, I think we’ve redefined it even further, twisting it and his quote to suit our own ideas.Language is constantly changing. When I was growing up, “out of pocket” meant hat you had to pay a bunch of money because your shitty insurance wouldn’t cover something they said they would. Now it means ridiculous or crazy, though in retrospect, I see the connection.There are two types of people when it comes to definitions and word usage: prescriptivists and descriptivists. Prescriptivists want words and meanings to remain as unchanged as possible. They want unchanging grammar, standardized usage, and regular spelling. Descriptivists look at how language is actually used rather than how it’s “supposed” to be used.Normally, I am more of a descriptivist. I understand the need for standarization when it comes to writing, but languages are fluid and constantly changing. I love looking back through etymologies and seeing how usage and definitions have changed over the years and centuries.But not here. Again, this is a pet peeve. I won’t be budging. With the take vs. make argument, I’m a prescriptivist. It’s take. Always has been.However, the descriptivist part of me finds it a little interesting to see how the usage of “make a photograph” has slipped since Adams said it in 1935.The Original QuoteBut there’s something more to this. We’ve taken a look at the quote (“You don’t take a photograph, you make one”), but I haven’t told you the whole quote, the full context.Are you ready? Because I don’t think you are.“The unique quality in photography is a combination of rigidity, based on the pure physical, scientific facts of life, and the possibility of controlling that rigidity. You don't take a photograph, you make it. Expression is the strongest way of seeing.”This appeared in a 1979 issue of Time Magazine. The quote is not sourced, but I believe it comes from his 1935 book, Making a Photograph. Ansel Adams was a wonderful photographer, but his writing leaves much to be desired.I spent hours upon hours trying to source this quote to no avail. What I also found is that the quote we know, the “You don’t take a photograph, you make it,” doesn’t show up on its own until after his death.For how often it’s quoted, and for how much it’s associated with Ansel Adams, you'd think that this was some motto he repeated constantly. That his friends would all roll their eyes and leave the room, "oh god, Ansel’s going on about making a photograph again!”. You’d think he had it tattooed on his chest. With a few buttons missing, just across his bulging pecks you could read “you don't take a photograph, you make it."This was something he said of course, it was something he believed, I guess, but it wasn't central to anything he did.The more I consider it, the more I think that while Ansel Adams said those words, he had no idea how far-reaching an impact they would have. It was just a clunky sentence lost among other clunky sentences.The photography community seems to have co-opted his words and memories, making the quote what it is today. We gave it a different meaning. We completely changed the intent. Ansel Adams had very little to do with what is his most famous quote.A Bit About Adams & PictoralismWhen Adams started taking photography seriously in the early 1920s, he had just missed the war going on in the art world. In the early days, photography was largely used to document things and for portraiture. It was not seen as an art, especially not on the level of painting.Photography was a science. You needed certain chemicals in specific amounts, there were beakers and bubbling sounds, every darkroom was a laboratory. Most painters saw photography as a rigid science, not as an art. Hell, most photographers agreed.But around 1880 that started to change. Some photographers like Gertrude Kasebier, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Steichen insisted that photography was art, actually, and their style often pulled inspiration from impressionistic painters. This resulted in the Pictoralist movement, with photographs in soft focus and dream-like. Adams caught the tail end of this movement, and his early work is in that style.While he missed the war between art and science, he was starting to wage one