Nearly Dying Alone in a Utah Canyon

Description

Hello and welcome! I’ve got a story for you. It’s about the time I dragged way too many cameras into a Utah Canyon. Did I get any photos? Did I see cool stuff? Did I ever return? Find out!

This is a longer one, so strap on your backpacks, grab your cameras, and make sure you have enough water. We’re going in.

I stood overlooking the canyon two hundred feet below me, deepening, falling and twisting west into the late July sunset. Returning to my tent, pitched under the relative shade of a cluster of juniper trees, I checked my pack. I was nervous and alone.

Solitude had marked every turn of this trip and now, after nearly a month on the road, I was worn. This was my final stop and in a few days I would be home. But first, I needed to explore the canyon below me.

I don’t remember when or how I first heard of Bullet Canyon, a tributary to Utah’s Grand Gulch in Bears Ears National Monument, but seeing photos of Ancestral Puebloan cliff houses and kivas, nearly untouched, I had to experience these myself.

In the spring and autumn, this is a popular trail seeing a couple groups a week. By July, with temperatures often over 100F in the depths of the canyon, there’s nobody. In March and April, there are several springs and even a stream at the bottom of Bullet Canyon. By July, they’ve been dried up for months. Any water you need has to be carried in.

This was far from my first ten mile desert hike. I fully understood the need for carrying more water than you think you’ll need. The heat itself, not to mention the physical act of walking ten miles, would dehydrate me. I knew the symptoms of heat exhaustion and the dangers of succumbing to it alone. I’ve learned how to hike in these places from experience. This wouldn’t even be my first summer Utah canyon hike. It was, however, my longest.

I emptied my pack to make sure I had everything I wished to bring into the canyon. I had a 4x5 camera (I was shooting an Intrepid then), wrapped in a dark cloth with a 150mm lens, six film holders (so, twelve shots) and a small tripod. I also brought two 35mm cameras: a Ricoh and a Soviet-era Smena 8M. For overkill, I also carried a plastic 1960s Imperial Savoy and the metal Ansco Color Clipper. Five cameras just in case.

I also carried my lunch, some snacks, and 1.5 gallons of water. This would be a ten mile hike along some fairly rough trails. I sliprockhad my map, my ten essentials, and a little less courage than I thought I might.

Through the night I heard coyotes and owls. But there were no visitors, no other campers, no other hikers. I drifted into sleep alone and woke up before dawn alone.

Striking my tent in the pre-dawn, I stashed it in my car parked at the trailhead. I slid my arm through a strap on my pack, and then the other, jumping a bit to settle the weight. I buckled the belt, picked up my trekking poles and looked out over the canyon once more. The light was enough that I could see much of the day before me, though much of the canyon was hidden behind bends and turns.

At the start of the trail is a register. Every hiker is expected to sign in, noting the date and time. I was the only hiker in over a month. If anything happened to me, there’s almost no chance I’d be stumbled upon before I was bones. I had told folks at home where I’d be hiking and when to expect me: probably around 1pm, but 3 or even 4pm at the latest, and if I wasn’t back by five, they knew to contact emergency services. There was limited cell service at the trailhead and nothing at all in the canyon. Except me. I was the only one here.

I stood overlooking the canyon two hundred feet below me. There was no real path to get inside, though I could see one at the bottom leading to a dry wash that would serve as a trail. There were car-size sandstone boulders strewn along the descent. There were a few juniper trees clinging as they could to various smaller cliffs. And I picked my way along them, lowering myself, sliding from tree to tree, and wondering how the hell I was going to get back up.

The thought of turning around haunted me and I brushed it aside. There was some danger, to be sure, but it’s not like this was an unexplored trail. I would pull myself out of the canyon when it was time.

A number of rock cairns guided me from sliprock to sliprock until I finally reached the bottom: a red and hardened sand wash among some taller junipers. The sun must have been up by then, but I wouldn’t be able to see it until it was much higher in the sky. And by then, I knew I needed to be nearly at my turnaround spot, about five miles down the canyon from where I now stood.

The descent took something like two hours.

I rested for a few minutes when I hit the bottom, and then continued, making good time as the walls of the canyon grew taller and more narrow as the wash cut deeper into the land. I walked and felt the weight of the pack. Mostly, it was the water. A gallon and a half weighs over 12lbs. I considered stashing some of it along the trail, but if I were going to do that, I would have carried an extra bottle. I was going to need all 12lbs of this water. With that, I took a drink.

As I walked, I could already feel the temperatures inside the canyon rising. It can be as much as ten degrees hotter inside than on top. The air is compressed down here and compressed air releases heat. The difference wouldn’t be so stark just yet, but as the hours wore on and as I pressed on, soon I would feel it.

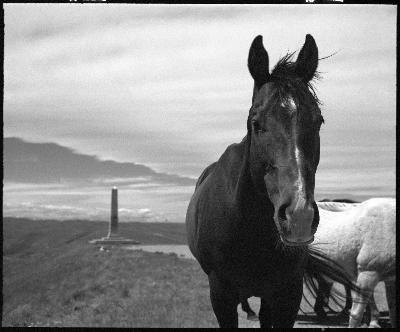

Not long after starting from the bottom, a stone tower overlooked me on the cliff heights above. It was today’s first Ancient Puebloan ruin, and much too high for my lenses. I paused for a moment in appreciation and felt like I was being observed from above.

This tower saw me lumber on, pack now weighing upon me, digging into my shoulders. There wasn’t pain so much, but I could tell that pain wasn’t far away. My feet weren’t yet aching, but they would be before long. And it saw me take another drink.

The trail itself isn’t really a trail at all, and it’s hardly ever used. It’s a dry wash, sometimes deep with sand, sometimes (and more usually) strewn with the debris of flash floods — trees, boulders, a tangled mess to stumble and cut my way through.

There were miles of this, with the canyon meandering and bending sometimes almost back in upon itself. And with each mile, I descended deeper into Grand Gulch. The canyon walls grew taller as the temperatures rose higher.

I was often fully exposed out of necessity. The easiest path was the wash, with much of the rest of the floor tangled in brush and thorns. The wash was also a highway of sorts for wildlife. Mostly it was deer prints, pressed softly into the red earth. Here and there were small skittery footprints of lizards and rodents. At times there were side paths, likely made by animals, and sometimes they were shortcuts. Other times they simply disappeared into thickets. It was best to tramp out in the open. But it was also hot.

The sun had finally found its way into my narrow skies, though by now the canyon was widening and still growing deeper, like I was being swallowed. I walked with the 35mm Ricoh around my neck, snapping a shot here and there.

There were times when the canyon floor would open up to an almost pastoral setting. Golden grasses waved in whatever breeze was blessing us, and at one point, a tall cottonwood tree grew among them. With the sun now higher, its leaves twinkled and I did my best to photograph it.

But then the canyon closed up once more, the walls grew nearer, and the floor dropped about six or seven feet. If this dry stream bed wasn’t dry, here would have spilled a waterfall. I assessed the situation. I could slide down it, but could I scramble back up? There was no way around this. Though the top of the canyon here was wide, the stream had cut a near perfect V shape, funneling everything, including me, to this drop.

With no small amount of apprehension, I slid down the dry waterfall. At the bottom was a rock cairn marking the way, almost tauntingly as there was no other way to go.

Here the path was narrow and the closest walls very close. This cast shadows even in the late morning. I stopped here to do a full rest and take a drink.

A full rest, at least for me, is where I take my pack off and lie down with no weight on my feet. I try to do this for ten minutes. When I’m anxious and excited it is less. When I am dragging and beat, it is more. Now it was less. I was still feeling good.

I removed the Ansco Color Clipper from my pack and took a bad photo of the dry waterfall. I exchanged it with the Ricoh, always wanting to have one camera at the ready. This would also distribute the weight. My shoulders might give some faint thanks, but my knees and feet would not tell the difference.

The going was slow and I was slow and stopped here and there for photos and water. It had been four hours since I had reached the bottom. The sun was not quite at meridian, but was closer than I had hoped. I was not making good time, though the point of this hike wasn’t to get back quickly, but to experience the Ancient Puebloan cliff dwellings. And now, after nearly six hours total since I left camp, they were here. Somewhere.

Within a half-mile of each other were the two main sites I wanted to visit. This canyon and an adjoining one contain dozens of such places with pictographs and petroglyphs decorating them all. Today, I had time only for two. But these were the two prized sites. And they were here before me if I could only find them.

One of the features of these cliff dwellings is that they were difficult to spot and difficult to access. I knew roughly where they were, and scanned the cliff walls with squinted eyes.

Two circles about a hundred or more feet up caught my eye. There it was, Jailh