I Was Wrong About Solitude and Isolation.

Description

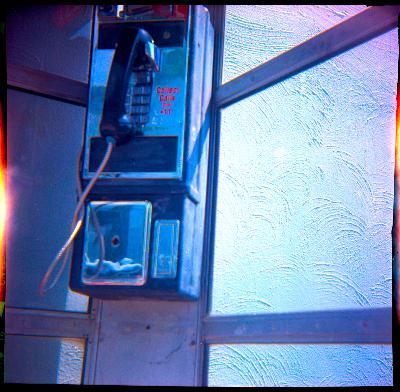

If you look through my photos, you will see pictures of abandoned buildings, of houses left empty, of roads seldom driven, of paths sometimes walked only by me. You will see endless photos of old towns, empty cars, power lines, bridges, and railroads. But you'll almost never see a photo of a person, let alone a portrait.

It took me years to realize that I shied away from this. And maybe that's what it is, maybe I am shy. Too shy to ask if I could take your picture. Too shy to learn just how to make it good. Too shy to extend myself to make that connection.

But part of that realization was that while I don't take pictures of people, I do take pictures of humanity, though maybe that isn’t the right word (as you’ll see soon enough). Maybe I take photos of personality.

People

When someone first pointed out that I didn't take pictures of people, I almost didn't believe them. I will roam from town to town, taking many photos, talking to many people, seeing them on the streets and in their cars and in their houses, and yet, rarely have they ever appeared in my photos.

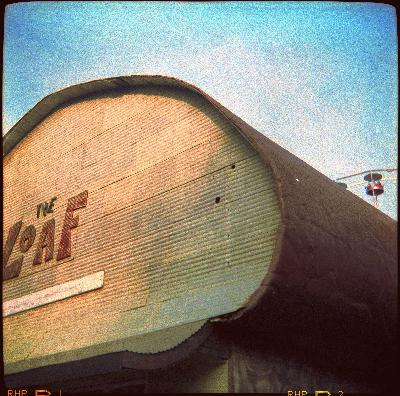

All of these subjects, all of these places that I photograph, were once peopled, were once inhabited. Some still are. Nearly every photo of mine has some record of human interaction with nature.

I have fallen in love with this interaction, this relationship between humans and nature. I don’t even look for it anymore, I just see it. In every place I visit, every photo I take, there it is.

I used to submit some of my photos to an online group that focused upon nature photography of Washington. Their only rule was that there was to be “no hand of man” – obvious evidence of human occupation or manipulation. But almost everywhere in Washington, almost everywhere in America, you can’t find what we think of as nature without the hand of man.

The trails we walk, the hills we climb, the streams we swim were all affected by this mysterious “hand of man.” Perhaps it’s not so obvious as a paved highway through a forest, but the lasting ramifications of our relationship with nature are everywhere.

Nature (Animals)

Our usual definition of nature is anything outside of human interference. It’s tempting to suggest that our view of nature is faulty – that maybe humans should be counted as part of nature rather than separate. This makes sense in so many ways, especially because of how we now build our houses, our cities, exiling nature to the outskirts, and well-managed parks.

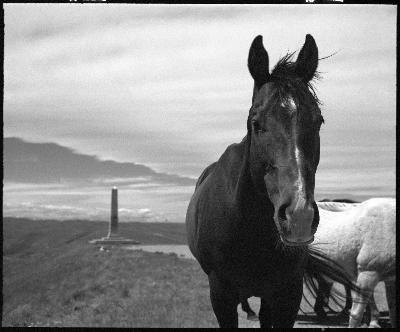

But in another sense, maybe it's our perception of people that is faulty. Our idea of personhood and personality is very narrow. We see ourselves in it, of course, and sometimes we extend it to our pets, which is understandable. But almost never does it cross that line, almost never does it leave our house, our property, our bubble.

And yet, it shouldn't be a stretch to see other animals as people. We give names to our pets. We see the personalities in our cats and dogs. And so it shouldn't be insurmountable for us to see the animals we come into contact with in the same light. Maybe we aren't as familiar with their ways, but we could be. There's very little stopping that from happening. Maybe it’s our shyness. Maybe all of us are as shy with the animals as I am with people.

I don’t take too many photos of animals, if I’m being honest. I shared a couple of stories not too long ago about photographing some cows. I’ve also photographed a bird or two, when I got the opportunity. And, of course, there are the photos of Juniper on her deathbed. It was a devastating honor to take those photos.

I do wish I could take more photos of animals, but it isn't shyness that's stopping me, it is skill and maybe patience. I don't have the patience to be a wildlife photographer. Also, most of my lenses are wide. In many photos, there must be hidden animals, unseen, staring at me, wondering what I am doing with a 90 mm lens. If only they could tell me.

Nature: Plants

But why not the plants? In some narrow ways, we are familiar with seeing plants as people. We raise and talk to, and even name, flowers and ferns. There was a prayer plant who lived in my house, and his name was Greg. I didn't name him, but he came to the house with that name, and it stuck.

Many of us fawn over the flowers and vegetables growing in our gardens, and we form what logic tells us is a one-way relationship with them. But somewhere inside, we do understand that there is an exchange happening. Even materially, we water them, they grow, in return, they make us happy and fill our stomachs.

So why not the plants in the wild? Why not the trees, the grasses, why not the wildflowers and sage? Even in the cities, plants are more plentiful than our human neighbors. And they're often much easier to deal with.

Other People

I don't think I've always seen plants and animals in this way, but I'm having a hard time remembering when I didn't. It's something that I simply haven't given much thought to. But when I look through my photos, I can see it’s there. I am, in a way, taking photos of people. Maybe they aren't human people. And many of them aren't animal people.

But I take portraits of trees. I focus in on flowers. They are not, as we often mistake, inanimate objects. They have life in them. They cycle through birth, disease, and death the same way we do. We have much more in common with them than we do a house, or a bridge, or a car.

There is a world going on around us, under our feet, above our heads, and in some ways, we are connected to it. But in most ways, I think we've neglected it. Maybe we’ve forgotten. Maybe we've never had it.

When we were babies, did we really see much of a difference between our older sibling and the dog? Didn't we have a favorite tree? Didn't we have that childhood urge to run to the forest?

I was fortunate enough to grow up in a small town surrounded by farmers’ fields and woods. A large creek bordered one side of town, and I’d spend entire summer days running through the trees, scrambling up hills, building forts, and catching turtles and bugs.

I learned quickly that if I sat silent and still, birds and squirrels would get used to me, ignore me, and go about their normal business. There were special moments when I’d see deer creep close for a drink, eyeing me all the while. And even when the deer and the squirrels weren’t around, I discovered that I could sit by a stream and just listen to its murmuring.

Our Inanimate Friends

So really, why stop at plants and animals? Couldn't the water also be a person? It can be calm and still one day, and full of anger and violence the next. We see that in ourselves. We see that in animals. And we can see that in the rivers and streams, the ocean, especially. None of these beings is inanimate.

Even the rocks, though they are still and solid, are not inanimate. It may take millennia, but they can move. Even mountains can move. There is a mountain in Washington that many geologists are starting to figure out that moved from Baja California. In fact, much of Washington state is made up of tiny islands that were in the Pacific Ocean. They've all gathered together to make the home where I live now. And yet we think the land is inanimate because our lives are too short to see its motion.

Nature Is Motion

As photographers, we can show the personality of animals and plants, of water, and even mountains. And I've always found it important to do so.

Many photographers who photograph nature refuse to take their pictures when the wind is blowing. They want to take a beautiful photo, with a tight focus and a wide aperture. They want a tripod and the fastest shutter speed to negate any movement. I never understood this.

All of nature is in motion. All of life is in motion. Even in death, we are still moving, the bugs wriggling around in our bodies, the worms in our guts. It's all motion. There's no way to escape it. As photographers, why are we trying to deny this?

When I take a photo of, for example, an abandoned house, I try to show the uniformity it has with the nature around it. I try to show how it has changed and bent to the landscape. But I also try to show that everything around it is in motion by letting the shutter linger open for a second or more. I'll wait for a breeze if there is no wind, I will watch for the grasses swaying, and the tree limbs moving, and then I will open the shutter and wait, capturing more than just a quick sliver of light. I'm capturing a moment. I'm capturing a period of time, an era.

Maybe all of my photos are motion pictures, in this way. But it's my way. I've only ever done it like this. I love seeing the movement. I love being reminded of how the stream is alive, the grasses are living, the leaves in the trees are waving. The blur that is present on film represents the opposite of what most nature photographers are trying to capture.

Most nature photographers take after hunters, seeing something in the forest, a flash, and firing their gun to stop it. In fact, this is where the phrase snapshot was derived. Originally, it was a hunting term.

But I long for the opposite of this. I go to nature to observe it, to live in it, and, as a photographer, to bring a little of it home with me. Not as a taxidermied trophy on film, but as my memory holds that moment. I want to capture how the moment felt just as much as how the moment looked. But still, nature photographers who freeze time with no movement at all fail to do this. They fail to move me.

Home and Homes

This isn’t to claim that I never take photos of solid architecture, divorced from any nature around it. I do, and I enjoy that to some lesser degree. I take pho