How to Start, Kill, and Resurrect a Project

Description

All the way back in the first post, I told you about my travels and trials of the summer of 2024. I ever so briefly mentioned visiting and exploring some of the railroad towns along the Virginia/North Carolina border.

“I will have much more to say about these towns and this experience in the future (possibly a zine will come of it),” I said, long ago.

The future is now! And a book has come of it. [You can get it here.]

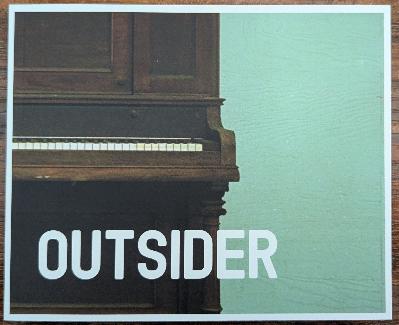

I’d like to tell you all about it, but I don’t want this just to be some commercial for the new book (which is called Outsider, and I’d love for you to see it). So, instead of just hawking the book, I’d like to take you through the process of how I produce a photography project. Every project must start with a plan.

The Plan

When I travel, I do so based almost entirely around photography. Every stop, every road, every minute of sunlight of every day is about what I can shoot, how, and when. Obviously, I can’t plan for everything, and last year’s trip humbled the hell out of me. But when I plan, I pretend that the plan will not go awry.

The bulk of this trip was about cemeteries. For the most part, I ignored the towns, focusing instead on the roads I could take between one old, abandoned cemetery and the next. I figured maybe I could shoot something along the way. It’s a method that has served me well for as long as I’ve done it.

There was one section, however, where I wanted to focus on the towns themselves. I used to do this almost exclusively – plan to drive the most interesting roads from one town to the next – and so falling back into that was simple.

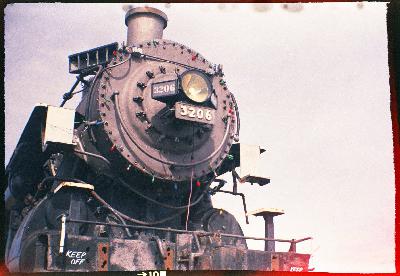

I discovered these towns for myself through my friend Bob, a fellow photographer and traveler. He was able to capture these towns, focusing mostly on the railroads, but exploring the downtowns and sidestreets as he went. His photos reminded me enough of the ones I used to take, and I wanted a bit of that for myself. Along with Bob’s suggestions, I used Google Maps to solidify my plans.

My planning of this area became one of the main focuses of the entire trip. So much so that I wanted to make this an entire project, with a book for the photos and short essays about the history of each town. I’d center it around the railroad (Bob isn’t the only one with an interest in trains; mine dates back to before I can remember) and pick up whatever other history might be lying around.

I selected the towns based on where the railroad was or had been. I simply followed the track on the map and noted each town. I then looked through Bob’s photos for that town (he has shot almost all of them) and then decided if it looked like a place where I could make something happen.

Of course, the thought of plagiarism was bouncing around my head much of the time. What was the point here? What was I doing? But I wasn’t just copying Bob. We see things in different ways. Even if we had shot together, the results would be almost like we photographed separate towns.

I would start in McKenney, Viriginia along the I-85 corridor and move south, zig-zagging through places like Stoney Creek, Capron, and Boykins, before crossing the line into North Carolina for Rich Square, Aulander, Robersonville, Rocky Mount, and Roanoke Rapids. I’d end by trailing off west with Henderson, Oxford, and Roxboro.

The Gear

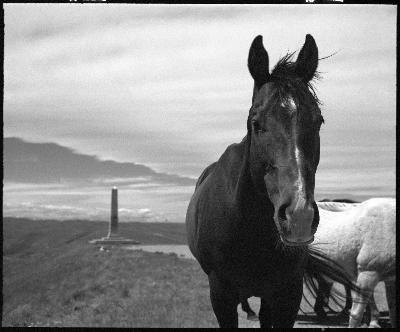

There are some projects that demand an almost chaotic array of photos, taken with various cameras or lenses, a multitude of styles, and as many different emulsions as possible: color, black & white, and numerous samplings of all of them.

For this project, however, what I wanted was uniformity. Every photo wasn’t to look the same, of course. I’m neither Bernd nor Hilla Becher here to create a typology of small southern railroad towns. But still, I wanted it to all be of a piece.

What I expected from the middle-south in July was heat, humidity, and sunshine. I keep saying I’m moving away from color, but it keeps dragging me back. And so color it was. I had recently received about twenty rolls of Kodak Ektachrome E100S which expired in July of 2002, nearly 23 years ago. I had already used a roll or two, and knew it was good, and knew it was well-behaved in how I develop color.

I develop all of my color film using the ECN-2 process. I make my own kits from raw chemicals. I even sell them and you can buy them, but this isn’t a commercial.

My go-to camera is a Mamiya RB67 with a 90mm lens, one of the early lenses shaped like a bell with less coating than the newer ones. It’s a camera that makes a statement, but it’s also my daily driver. I considered running the film through a 1912 Kodak Brownie box camera, but I thought it would be a better idea to have some sort of control over the exposure. I will never know if this was the right decision. But that’s how projects work.

The Execution

But that’s also not how projects work. Projects change over time, over the course of doing them. When planning, we have to be rigid enough to stick to our project but flexible enough to change and adapt rather than giving up.

I had spent too much time in Pennsylvania, and I knew I would have to cut parts of the trip short, but I wanted to keep the Virginia/North Carolina portions intact. My original plan was to explore a bit of the Blue Ridge Mountain towns, but I cut that to save this.

My first night out of Pennsylvania, I camped at a private campground that I think used to be a KOA. In the west, where I usually travel, camping is often very cheap in National Forest campgrounds or free on BLM or other federal land. The East Coast is different, but I knew that going into this. The campground was expensive in comparison, and I’d have to get a hotel room or two before all this was out. This might be my most expensive photography project to date (those hotel rooms add up quick).

After setting up the tent, I headed out for some evening shots of Dewitt, McKenney, and Wesson. I was already off the original plan. In each town, I’d park and just walk around. I had noted a few landmarks here and there to draw my attention, but mostly I just wanted to see what the towns had to offer. It was a Sunday night, and every town, even the busy ones, was empty.

On Baker Street in Emporia – a town that wasn’t in my original planning – I found a colorful row of boarded-up storefronts that once were an extension of their still-busy downtown.

With each photograph I took, I was trying to think forward and back, “would this shot work with the others I’ve already taken?” It’s a question that’s fairly unnecessary to a project, but I find myself editing on the fly, and it feels right for me, so I usually go with it.

The sun was near setting, so I returned to my car, and then to my tent, and then to sleep.

The next day was the biggest. Like any day I travel, every minute of light is a minute when I’m working. I rarely take breaks, and often have to force myself to stop for lunch. I did not eat lunch this day.

I collected a few shots in a few towns early, but nothing really seemed to be working at first. I couldn’t find my place in the day, and was getting a little worried.

On my list was the Nat Turner memorial. There was nothing to photograph here, but I just wanted to see it. In 1831, Nat Turner led a slave revolt that scared the hell out of the country. It lasted for four days before being put down by the military. When I drove to the spot of the memorial, I found nothing at all. With a sigh, I moved on, crossing into North Carolina.

In Conway, I found small cottages along Church Street. There was a story here, but I couldn’t tell what it was. Were these repurposed company houses built by the railroad? Whatever the history, the morning light was beautiful upon them.

I drove, walked, and photographed my way through these towns as the sun rose towards midday and a more uniform light fell over everything.

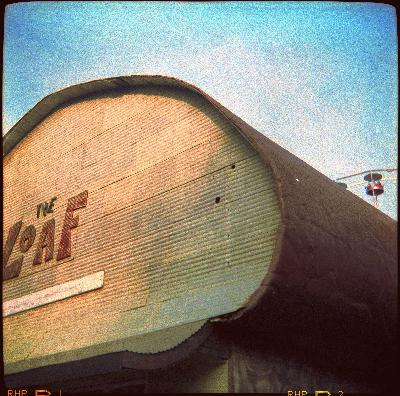

It was mid-morning when I entered the town of Ahoskie. A quick drive through downtown showed me a thousand possible photos. I parked and spent an hour walking up and down its streets.

In some ways, I am an explorer, but I rarely take my time to truly explore a town. I rely on happenstance and planning. I don’t dig as much as I should, as much as I would like to. But here I did.

The downtown is not dead, but it has consolidated, leaving many vacant storefronts standing. It was Monday morning, and many of the shops that were still open were still closed for the weekend.

But in the window of an old storefront that was now being used as a nondenominational church, I framed the reflection of an old appliance store across the street. “Color / Zenith / Color” read the sign, not fully faded in the lifetime of sunlight it’s endured. I shot the store straight on as well. The light was wonderful.

I took a similar walk through Williamston, framing a shot of a former service station still holding to its foundation next to a 70s looking Wells Fargo building.

Nearby, in Robersonville, the town was built around the railroad, with the track splitting what was once the main thoroughfare. There, I found an aging funeral home, a barber shop that hadn’t seen a customer since the 80s, former banks and ministries. As in the other towns, they weren’t dead, but compressed. I have seen enough small towns to know that these were still very much alive.

But there was something markedly different about them. It wasn’t that something was off or I felt unwelcomed – I knew all too well what that was like; some of the towns in the west and even midwest almost encourage you not to stop. This was welcoming and friendly. There was a lived-in warmth here. But there was also a sto