Balancing Photography and Hiking

Description

I had packed the night before - camera, film, water, food. I had checked maps, selected my trails, and committed them to memory. This would be an easy hike, I thought, but then recalibrated. I am out of shape, this is the first hike of the year (first hike in a year), and I haven’t felt great in months. This will be what it is.

It’s not that I didn’t care, but I had to get out. The winter and early spring of Seattle was suffocating me. The constant noise of cars, the echo of far too many voices, the monotony of concrete and asphalt and concrete was walling me off, brick by brick.

There’s a balance we try to strike as photographers between living in the moment and photographing that moment. It’s impossible to do both, though we often tell ourselves otherwise.

We lie to ourselves, saying that while we are experiencing the through the lens, it’s still happening and we are still fully present. We want so badly for this to be true, even when we’re not hiding behind the camera. Experiencing the moment without the filter of a lens grows terrifying the more time we spend behind it.

It was tempting to leave the camera at home, but of course I didn’t.

What I did was a compromise I made with myself years ago. Each hike, I make some vague attempt to carry my camera inside my pack. Of course, this runs antithetical to the photographer’s philosophy/film manufacturer’s marketing slogan of always having a camera at the ready.

This, I’ve found, allows me to experience the moment first, and then hide behind my camera. This also means not capturing some of the moments. But then, this is also a rule I end up breaking to no real advantage by the end of the hike.

With large format a pack is necessary. There’s really no other way to carry a tripod and camera that needs a tripod (as well as film holders) into the field. But I’ve also started doing it with medium format, lugging the boat anchor known as the Mamiya RB67 on my back.

When I see something worth a photograph, I sling off the pack, unroll the top, take out the camera bag, take out the camera, and shoot. This entire operation requires only thirty seconds or so. The lens is already on the camera, the film is already loaded. All I need to do is check the light.

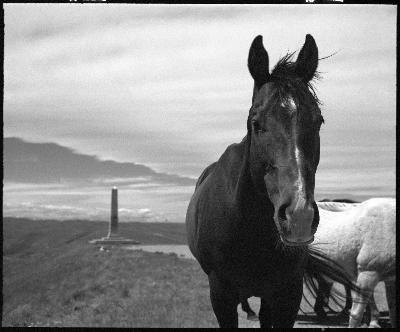

The sun rose softly behind thick morning clouds as I crossed the Columbia River on Interstate 90. I had left Seattle hours before dawn and regretted not camping the cold night before. The light was dim and gray, and though I was there to photograph the spring wildflowers, I had brought enough black & white film to last the entire hike should the clouds fail to disperse.

Washington is known for its lush forests of firs and moss, its tall granite peaks, and glacial lakes. But that is almost never my destination. East of all that, on the other side of the Cascade Mountain Range, lies an almost prairie landscape full of sage and grasses intercut with seemingly inexplicable dry box canyons. It’s called the Scablands, and that’s an awful name for one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen. This is the shrub-steppe, a (nearly) desert grassland that covers nearly one-third of the state.

While a few trees dot the landscape – mostly the invasive Russian olive tree – the rolling hills are covered with sagebrush, a slow-growing shrub whose leaves smell of camphor and mint. When it rains, the air fills with this scent and everything in the world seems perfect, even though it really, really isn’t.

When I arrived at the trailhead, there were more cars than I had ever seen there before: fifteen. Maybe sixteen. Had my spot been blown up? I wondered, reminding myself that this wasn’t my spot, that I’m only here a few times a year. This is public land, and it’s ours. But still, that’s a lot of cars for a place three hours from Seattle. I parked, double-checked my gear, took a long drink of water, and started down the trail.

The hike was at a place known by a few different names. Most commonly, it’s called Ancient Lakes – a misnomer we’ll come back to. But it’s also called Potholes Coulee, and has been for nearly a century. This is a state wildlife area known as the Quincy Lakes Unit, part of the Columbia Basin Wildlife Area.

The main features, apart from the lakes, are two half-mile wide canyons running parallel, east and west into the Columbia River, for two miles with a thin spine separating them. From space, they look like a giant had pressed two fingers into the mud. The north canyon, Ancient Lakes Coulee, is the most traveled and visited. It’s the easiest to get to and has several small lakes inside it. The south canyon is Dusty Lake Coulee. They are not mirrors of each other, but hikers rarely do both.

But I would do neither this time. Over the years, I have explored and camped in both. I have walked in from the same trailhead, level with the floor of the coulees. And I have also scrambled the 250 feet down the side of the coulees from the top. I have hiked and photographed the overlooks, side canyons, wetlands, and oddities of this place for the last fifteen years.

Though the coulees themselves weren’t where the trail was taking me today, my first stop was a photo I have wanted to retake for years. Nothing was wrong with the original one. Or the one I took after that. But I wanted to see what I could do with it again.

A main trail – actually an old ranch road – leads you across the wide mouths of both coulees, here nearly a mile in width. Along the way, several trails lead you inside the coulees, with various branches splitting off here and there.

I tramped past the first main trail off, and then the second, cresting over the crumbled remains that divided Ancient Lake Coulee from Dusty Lake Coulee. From here, I looked east along the tall spine left standing. These were sheer basalt cliffs with columns like the Devil’s Fence Post or Giant’s Causeway. But they were here, unheralded and unnamed, tucked into the cliffside with some small sunlight piercing the clouds and showing their tall shadows. Looking a mile across to the other side, a small waterfall was lit up white by the sun, and it twinkled and shone. If I had time, I said, I’d visit it on the way out.

I backtracked some, returning to the trail into the coulee. My footprints were the only ones on it that morning, and I tracked over only the faintest of prints left in the mud some weeks before. This was the first warm weekend, more would be coming. But for now, it was just me.

What I was seeking was off-trail a bit, and I began angling away from the trail, moving through grasses, sage, and nearly-opened rock buckwheat flowers, stepping over tumbleweeds of invasive Russian thistle, until I found a century-old iron wheel stuck into the ground. What was left of its spokes was cut so the axle could be freed.

I don’t know what this wheel was attached to or why the wheel was left. I know nothing of it at all, finding it by accident as I roamed around a decade ago.

I slipped off my pack and removed the camera. I circled the scene a few times, deciding how to shoot it this time, forgetting how I shot it last, though maybe that’s for the best. When I reshoot a location, I try my best to forget how I shot it before. But I also want to photograph it differently, and so I try to feel my way into something new. Sometimes it even works.

The light was still dim, and I used 400 speed Ilford HP5 with a yellow filter to bring some small handful of contrast to the scene. Still circling the wheel, I shot several frames, including a close-up of a thistle branch. The sun cooperated by staying hidden, and I continued on, looking for the trail that would lead me lower.

If the coulees had flowing water, it would empty into the Columbia River, running perpendicular just a mile west of the trailhead. The land between the coulees and the river, 500 feet below, is a maze of tall, sharp outcroppings and dead-end narrow basins. Few trails lead down the various precipices, but I had found one that did.

The trail here was a well-cut walkway clinging to the side of a basalt cliff. Over the millennia, the cliff had shed, littering and piling thin rocks along its walls. Eventually, I thought, the cliffs will shed so much they will no longer be cliffs, but hills, steep and rolling. For now, though, walking over this uneven and precarious talus path, the view winding down to the river, still hidden in a canyon of its own, stopped me.

With the sun, still low and again behind clouds, the gray valley unfolded itself. The rocky path I was on descended to a landing lush with grasses and sage. As the cliff I was walking along faded away, another, opposite me, extended with various levels and shelves, themselves covered in grasses, leading to basalt walls and columns hundreds of feet high. Trails branched and combined within this small space.

Above me cried two ravens, flying side-by-side in the cool air. As they floated down into this little valley, towards the Columbia, one of the ravens turned upside down, tucked in their wings, and gave a quick and joyful “caw caw!” before flipping back and gliding with their friend. A moment later, the raven again flipped over, repeating the same call, and then back right. They did this several more times before flying back up the canyon, circling, and gliding back down again. As they escaped my view, I could still hear the upside-down “caw! caw!” echoing off the walls.

This is often seen as a mating ritual or a way to assert dominance, and both of those things might be true. But it’s also fun. Like most birds, ravens and crows fly to find food, to get from one place to another, for survival. But they also fly for fun. Ravens and crows play. I’ll often see my city crows sliding down roofs when it snows.

Taking some time to watch ravens in the wild is endlessly rewardin