The Absurd Competition of Photo Contests, also a Day at the Fair

Description

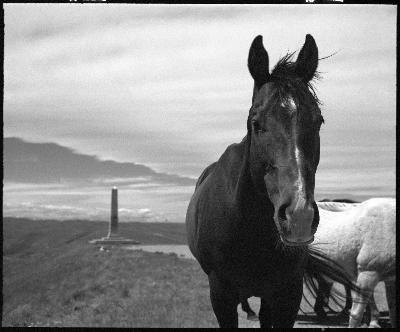

I took in the Evergreen State Fair in Snohomish County, Washington, last week. I walked the midway, avoided the games, and ate too many fries and too much cotton candy. There’s always some mixed feelings swimming around in my head about the animal exhibits. I avoided the cows, but took in the sheep. Saw a bunch of horses, and rolled my eyes at the dogs. I followed half a dozen “cat” signs with arrows only to discover that the cats were somehow not there that day.

Each of these stalls and pens had various awards and ribbons attached to them. Some won for showmanship, others won for driving; there were ribbons and plaques, banners and rosettes for a dizzying array of categories and classes.

While the baby goats were adorable (I booped noses with one!), and the Clydesdales were intimidating and majestic, the sprawling mass of other things that were judged was a bit overstimulating.

In the Arts & Crafts hall were ceramics, metalworking, various miniatures, and some diaramas. The quilts took up most of the room of the sewing hall, and they were impressive feats of bed-size, hand-sewn artistry.

This sat next to your very traditional county fair food: pies, cakes, breads, and jams. There were also homemade beverages and some of the best-looking produce I’ve ever seen.

Each of these items won some sort of award. Most had blue “First Place” stickers on them, while others had ribbons for “Best in Class.” Some ribbons made no sense at all to an outsider (Reserve Champion? Sweepstakes?), but it seemed like everyone did really well. Everyone got something. Good job!

And finally, an entire side of the huge exhibition hall was dedicated to photography. While I don’t know much about pigs or rabbits, bell peppers or apple pies, I do know a bit of something about photography.

The age groups for the photographers ranged from the youngest (ages four through nine) to senior citizens. There were also categories for Master Level and Advanced, though those designations were vague and essentially unexplainable.

So how do the judges at the Evergreen State Fair judge things like Aunt Ethel’s blueberry pie? Does the rabbit with the fuzziest tail win? The cow with the best moo? And, most importantly for us, how do they judge a photograph?

I don’t want to get lost in the weeds here, but technically, they use one of several systems that take into account expected standards (called the Danish Method). Sometimes they will judge on a curve (this is the American Method). There’s nothing objective or set in stone here. It’s really just the opinion of the judges. It’s a mood, a vibe.

Most of this is pretty low stakes. It’s bragging rights and maybe $25. There are generally no entry fees for county fairs (except for livestock), so the risk/reward is almost nonexistent. Of course, that does make one wonder why we do it at all. The way these contests are judged is nearly random. It’s a lottery. So why do we insist upon it mattering?

The Photography Exhibition

This wasn’t my first time visiting a county fair photography contest. Here, you’ll find photos of every kind taken by folks who are just happy to have their photo up in public, where it can be seen.

Like with the cows, the cakes, and quilts, these photographs had been judged, and ribbons and stickers adorned them all. You could win best in your category (and there are a lot of categories), best in your age group, best in show, and even sweepstakes (which still made no sense to me).

All of this was confusing since it seemed like nearly every photograph won something, and usually, 1st place. I asked the woman overseeing the photographs, but she just explained it to me just as I explained it to you, which solved nothing for me and will now solve nothing for you. But that’s fine.

Competition is nothing new. Our drive to compete for fun existed before humans, neanderthals, and even great apes playing throwing games (where you toss something and see who can toss it the farthest).

I don’t think there’s anything necessarily wrong with that; whether it’s a foot race or drag racing, I get it. Sure, it can be taken too far, but seeing if your ‘69 Chevy with a 396, Fuelie heads, and a Hurst on the floor can outrun the other guy’s on the quarter mile is just good American fun. Hell, I used to watch the Amish drag racing their buggies. As humans, we just love to race stuff.

And the whole thing is very simple: if you are quicker, you win. There’s really no debate; it’s purely objective. The “judging” makes sense. The same goes for most games. From football to roller derby, the team that scores the most points wins.

At the fair, when I asked about the photography judges and whether they were local professionals, one of the volunteers told me that all the photos were judged “by Rick.” "Is Rick a photographer?” I asked.

“Oh, he does many things, maybe he takes some pictures too,” came the reply. She then told me that Rick wasn’t here now, but he’s “probably in the pig barn, just look for the guy in the overalls.”

I did visit the pig barn, but none of the overall-wearing fellows were Rick, but all of this got me thinking: Just what the hell are we doing?

Incredibly Short History of Photography Contests

Judged competitions at county fairs date back to the early 1800s (and likely well before that in some shape or form). When photography became more accessible to the masses in the late 1800s, many fairs folded them into the competitions like so much Crisco into pie crust.

In 1896, Charles Emsley and Dr. Lombard were the “lucky ones in the photography contest” at the Western Montana Fair in Missoula. A local paper reported that “Mr. Emsley will wear the gold medal till next fair.”

But county fairs never had a monopoly on photography contests. The La Crosse Camera Company out of Wisconsin held a competition in 1895, advertising that they were giving away $1000 in gold to the winners. $200 for first place, $100 for second, $30 for third, and so on. [$1000 in 1895 is about $40,000 in today’s money.] The only catch was that you had to take the picture with one of their cameras (the La Crosse camera was a 4x5 box camera). The ad ran in papers all across the Midwest and East Coast (though a winner seems never to have been announced).

Even newspapers got in on the act. In 1957, the New England Associated Press awarded its “Best in Show” prize to Charles Merrill for his picture entitled “But ‘Twas Too Late,” showing two men removing the body of a drowning victim from the ocean.

Since then, it’s pretty much been the same – low stakes, low rewards (apart from the gold that possibly never existed) and essentially bragging rights.

Juried Shows Are Just Photo Contests

Of course, photo contests aren’t the only photo contests. There are also juried shows, which are a little bit different, though still very much photo contests. Typically, juried shows cost money to enter, and the selection process is more rigorous. In the end, however, the awards are typically small, and it still comes down to bragging rights.

Yet, juried shows are held in much higher esteem than county fairs, which is why they’re called “juried shows” and not “photography contests.” Juried shows didn’t start with photography; they actually come from the art world.

Still, they seem to have been amplified by the art schools of the 1920s, and were not always received positively. In 1929, the Chicago Art Institute held a juried show whose jurors received so much ire and criticism over their curation that they considered obtaining police protection since the public was, according to the Chicago Tribune, “sufficiently upset to fall upon the offending members eye, tooth, and nail.”

While the paper was almost certainly speaking in hyperbolics (after all, this was Chicago during the era of Al Capone), the jurors, as today, were acting as gatekeepers, and the artists were fed up with it.

If you ask galleries that put on juried shows, they extoll such benefits to the artists as networking, credibility, and the ever-important exposure. This is the same kind of exposure that musicians rightly balk at when offered low or no-paying gigs.

And to be clear, a juried show isn’t just a low-paying gig; it’s a gig the artist pays for. Each juried show has entry fees, typically around $25 to $50. That naturally doesn’t secure you a spot; it merely puts you in the running. The competition here isn’t just with the winning, but with the entering.

One of the “best” bits of advice given to artists considering submission to juried shows is to avoid experimental work or work that the juror doesn’t like. Here, you are essentially trying to please a single important person rather than your typical audience (or even yourself). What the jurors want or enjoy is the only thing that matters.

Gatekeeping and Democracy

With the advent of digital photography and social media, photography was heralded as finally being democratized. This was largely true. Apart from algorithms controlling what we see, the barrier to entry, even for film photography, is incredibly low. Like in the early 1900s, anyone could pick up a camera. But now, anyone can get their work seen by dozens and even thousands of people who would otherwise never see it.

This growth allows not only for novices to quickly learn their craft, but also for experimentation and innovation. These are the two things juried shows purposely dissuade, guiding the photographer to submit their “strongest” work, which here means work that will be strong enough to beat out the work of other photographers. Immediately, the vision of a strong photograph roundhouse kicking another dances through my head, and while I’m woefully overanalyzing the language her