097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]

Description

Welcome to Chapter XIV. This is the first of two chapters and about a dozen remaining posts that cover the context, development, and release of Windows 8. Many reading this will bring their own vivid recollections and perspectives to this “memorable” product cycle. As with the previous 13 chapters and 96 posts about 9 major multi-year projects, my goal remains to share the story as I experienced it. I suspect with this product there will be even more debate in comments and on twitter about the experiences with Windows 8. I look forward to that. This chapter is the work and context leading up to the plan. Even the planning process was exciting.

Back to 096. Ultraseven (Launching Windows 7)

In the summer of 2012, I was sitting across from BillG at the tiny table in the anteroom of his private office on the water in Kirkland. The sun was beaming into my eyes. In front of me was one of the first boxes of Microsoft Surface RT, the first end-to-end personal computer, general-purpose operating system, and set of applications and services designed, engineered, and built by Microsoft. In that box sat the culmination of work that had begun in 2009—three years of sweat and angst. After opening it and demonstrating, I looked at him and said with the deepest sincerity that this was the greatest effort and most amazing accomplishment Microsoft had ever pulled off.

Later that same week, I had a chance to visit with Microsoft’s co-founder, Paul Allen (PaulA), at his offices at the Vulcan Technology headquarters across from what was then Safeco field. I showed him Surface RT. I previously showed him Windows 8 running on desktop using an external touch monitor. At that 2011 meeting he gave me a copy of his book Idea Man: A Memoir by the Cofounder of Microsoft and signed it. Paul was always the more hardware savvy co-founder, having championed the first mouse and Z80 softcard, and had been pushing me the whole release of Windows 8 on how difficult it would be to get performance using an ARM chipset and on the challenges of hitting a low-cost price point. Years earlier, Vulcan built a remarkably fun PC called FlipStart, which was a full PC the size of a paperback novel. Surface RT with its estimated price of $499, $599 with a keyboard cover, and a fast and fluid experience, resulted in the meeting ending on a high note. I cherished those meetings with Paul. I also shared with Paul, proudly, my view of just how much we should all value the amazing work of the team.

What I showed them both was the biggest of all bets. While not “stick a fork in it” done, by mid-2012 Microsoft seemed to have missed the mobile revolution that it was among the first to enter 15 years ago. In many ways Surface RT set out to make a new kind of bet for Microsoft—a fresh look at the assumptions that by all accounts were directly responsible for the success of the company. Rethinking each of those pillars—compatibility, partnerships, first-party hardware, client-computing, Windows user-interface, and even Intel—would make this bet far bigger and more uncomfortable than even betting the company on the graphical interface in the early 1980s. Why? Because now Microsoft had everything to lose, even though it also had much to gain.

With Windows 7, we knew we had a traditional release of Windows that could easily thrive through the full 10-year support lifecycle as we had seen with Windows XP. Windows 7 would offer a way to sustain the platform as it continued to decline in relevance to developers and consumers, while extracting value from business customers with little incentive to change.

Microsoft needed a new platform and a new business model for PC makers, developers, and consumers. The only rub? Any solution we might propose wasn’t something we could A/B test or release pieces at a time experimentally. Windows was the standard and wildly successful. It wasn’t something to experiment on.

While the company was 100 percent (or more) focused on Windows 7, we had started (drumroll for the codename please) Windows 8 planning five months earlier. We had the next step, a framing memo from me first. Then we had a planning memo from JulieLar, ready to go as soon as we all caught our collective breath after the release—no real time to celebrate more, and certainly no downtime.

Technology disruption is often thought of at a high level along a single dimension, but it is far more complex. Consider Kodak’s encounter with digital photography, Blockbuster’s battle with DVD-by-mail, or the news business’s struggle with the web. Great memes, sure, but one layer down each is a story of a company facing challenges in every attribute of their business, and that is what is interesting and so challenging.

Digital photos were more convenient for consumers, that was true. But also, the whole of Kodak was based on a virtuous cycle of innovation developed by chemical and mechanical engineers, products sold through a tightly controlled channel, and an experience relying on a 100-year-old tradition of memorialized births, graduations, weddings, and more. At each step of technology change to digital images, another major pillar of Kodak was transformed, sliced, and diced in a way Kodak could not respond. The magical machinery of Kodak was stuck because not one part of its system was strong enough to provide a foundation. Kodak didn’t need to also enter the digital market. The only market that would come to exist was digital. The only thing that made it even more difficult was that it would take a decade or more to materialize as a problem, and that during that time, many said, “Don’t worry. Kodak has time.”

While figuring out what to do next for Windows, we saw Blackberry facing a “Kodak moment.” Blackberry was not just a smartphone, but a stack of innovations around radios, a software operating system optimized for a network designed for small amounts of data consuming little power, a business model tuned to ceding control to carriers, and a keyboard loved by so many. In 2009, Blackberry still commanded almost 45 percent of the smartphone market, even though the iPhone had been out since 2007. That led many to find a false comfort in the near term and to conclude Blackberry would continue to dominate. Apple’s iPhone delivered a product that touched every pillar of Blackberry, not only Blackberry the product but Blackberry the company. Sure, Apple also had radio engineers, but they also had computer scientists. Sure, Apple also worked with AT&T, but Apple was in control of the device. And Apple was, at its heart, an operating system company. Blackberry had some similar elements up and down the entire product stack, but it wasn’t competitive. At its heart, Blackberry was a radio company. Blackberry seemed to have momentum, but market share was declining by almost 1 percentage point per month.

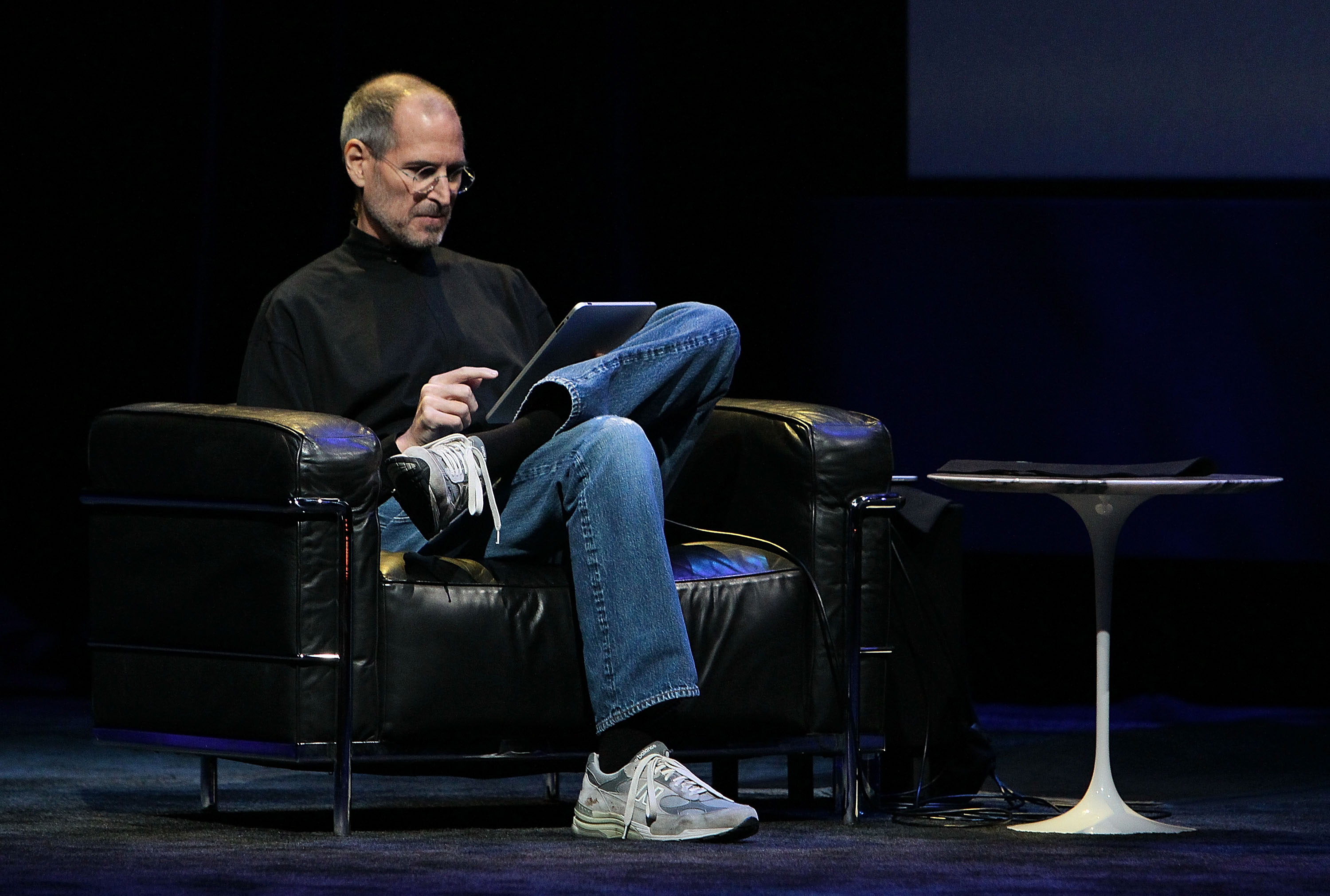

The smartphone, iPhone and Android in particular, was disrupting Windows. Though, not everyone thought that to be the case. Some said that phones did not support “real work” or “quality games.” The biggest risk to a company facing disruption is to attempt to dissect disruptive forces and manage each one—like add touch or apps to a Blackberry with a keyboard. The different assumptions and approaches new companies take only strengthen over time, even if eventually they take on characteristics of what they supplant. The iPhone might never be as good as the PC at running popular PC games, but that also probably won’t matter.

I’d lived through graphical operating systems winning over character mode, PC servers taking over workloads once thought only mainframes could handle, and now I found myself facing the reality that browsers could do the work of Windows, relegating Windows to a place to launch a browser and not even Microsoft’s.

Every aspect of the Windows business faced structural challenges brought on by smartphones. Compounding the challenge, Apple was competing from above with luxurious and premium products vertically integrated from hardware to software. Google, with Android and Chrome, was competing from below with free software to a new generation of device makers. The PC and the struggling Windows phone were caught in the middle, powerless to muster premium PCs and unable to compete with a free open-source operating system.

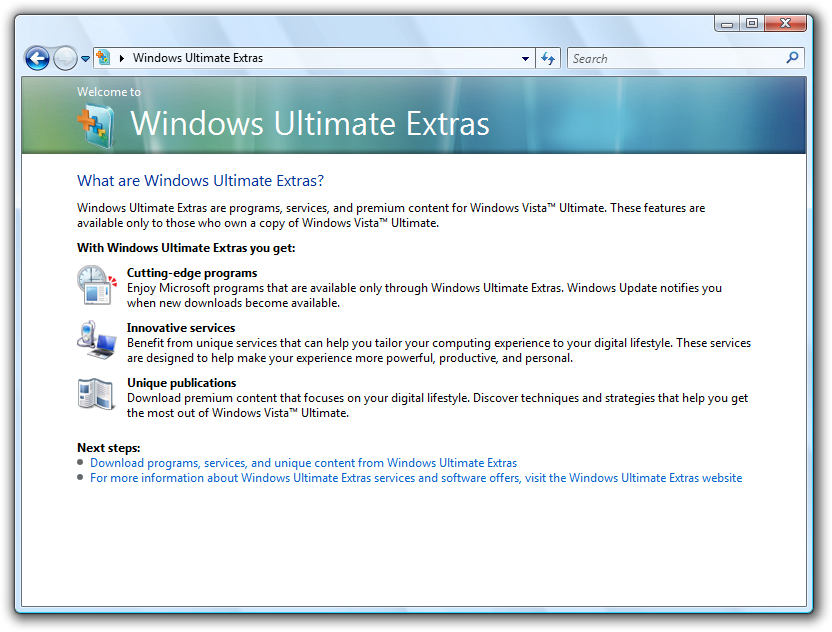

The browser had already shifted all new enterprise software development away from the hard-fought victory of client-server computing. Anyone who previously thought of building a new “rich client” application with Visual Basic or some other tool was now years into the transition to “thin client” browser software. The Windows operating system was in no way competitive with smartphone operating systems. The way to develop and sell apps had been reinvented by Apple. The Win32 platform was a legacy platform by 2009, the only debate was how long that had been the case. A legacy platform does not mean zero activity, but it does mean declining and second or third-priority efforts.

The partnership between the Windows operating system and hardware builders had fundamental assumptions questioned by Android. OEMs supporting Android not only received the source code but were free to modify it and customize it to suit their business needs. That was exactly what Microsoft fought so hard against in the DOJ trial. The touch-based human interaction model developed by Apple and the large and elegant touchpad on Mac were far more approachable and usable than what was increasingly a clunky mouse and keyboard or poor trackpad on Windows. The expectations for a computer were reset—a computer should always be on, always connected, never break or even reboot, free from viruses and malware, have access to one-click apps, while easy to carry around without a second thought. Tha

![097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV] 097. A Plan for a Changing World [Ch. XIV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/70543793/bbf82f6a403f39f35f097a445d9bf827.jpg)

![108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue] 108. The End of the PC Revolution [Epilogue]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/86893731/d3f1348af12bf87ffb878bd65cadb0ba.jpg)

![101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV] 101. Reimagining Windows from the Chipset to the Experience: The Chipset [Ch. XV]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/75881900/3a3075fad2c894721724f8a92013a812.jpg)

![092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII] 092. Platform Disruption…While Building Windows 7 [Ch. XIII]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/82387/post/64867897/fc7d958f8115ef0d95ea5a92c0d423b4.jpg)