A Christmas Carol for King George

Description

This story is true. Except for the parts with the ghosts.

[SFX: Theater applause]

Dim the lights.

Prologue. London. December, 1776.

One lone leaf on the London plane outside the King’s window trembles in the light breeze, like the whole city just let out a quiet breath.

It had clung to its branch through the long autumn, through winds that had stripped its companions and sent them spinning across the grounds of Windsor Castle. But now, in the stillness of a December evening, with no wind at all to speak of, it fell. The branch did not shake. The leaf simply let go, as if it had finally grown too tired to hold on, and drifted downward through air that smelled of coal smoke and coming snow.

It landed on the stones of the courtyard without a sound. A guardsman’s boot crushed it a moment later, unknowing. The groundskeeper would collect it soon enough.

Inside the palace, candles burned against the early dark. Servants moved through corridors with the particular silence of those who have learned that kings prefer not to be reminded of their presence. Fires crackled in grates throughout the residence, and the smell of roasting meat drifted up from kitchens where cooks prepared for the Christmas feast. The King had already declared he would not attend.

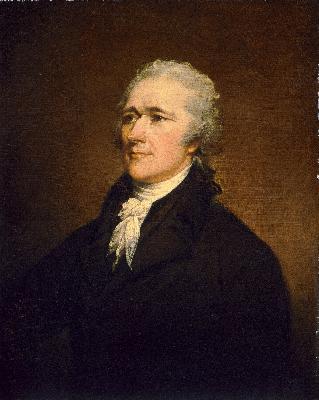

George William Frederick, by the Grace of God King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, sat alone in his private study. Most called him King George III. He was not yet forty. His hair had not gone white. His eyes had not drifted to that far-off place that later painters would catch. He blinked once, slow, like the weight of the crown had its own gravity. He was still a young king, or youngish. The rebellion in the American colonies had aged him in ways the mirrors had only begun to report.

On the desk before him lay dispatches from America.

He had read them twice already. He would read them again before bed. Again, when he woke. Again, mid-morning. Searching for the thing he could not find in them. An explanation. The reason. The sense of it all.

The rebels would not break.

This was the fact that he could not understand. Would not. By every measure that mattered, this rebellion should be over. The Continental Army had been driven from New York. Their capital had fallen. Their soldiers deserted by the hundreds, slipping away in the night to return to farms and families, to sanity, to submission. Washington’s forces had dwindled to a ragged few thousand, starving and frozen on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River.

And still they would not break.

George set down the dispatch and walked to the window. The courtyard below lay empty save for the guards at their posts, still as statues in the cold. Beyond the palace walls, London prepared for Christmas. He could not see the preparations from here, but he knew them well enough. The garlands and the wassail, the church bells and the charitable distributions. The goose being fattened in every household that could afford one, and many that could not.

Christmas. The celebration of a child born in poverty who had somehow overthrown an empire. George did not make this connection consciously. It floated somewhere beneath the surface of his thoughts, unexamined.

He touched the back of a couple of fingers against the glass. It was cold. On the other side of that glass, on the other side of an ocean, men wrapped their feet in rags, leaving bloody footprints in the snow. Men were choosing to freeze.

Why? What word had reached them that could make men choose cold over comfort?

He did not doubt the outcome of this rebellion. He had the strongest Army and Navy the world had ever seen. His generals would see to their submission.

But didn’t they understand what he offered? Order. Protection. The steady hand of a Crown that had outlasted plagues and pretenders, fires and mobs. A world where the rules did not change because a crowd felt hot blood in its throat.

Obedience, in return. That was all. One plain word, and it was suddenly the only word nobody in America could stand to hear.

He had read their pamphlets. Their petitions. Liberty was a thing you could hold in your palm and keep clean. As if “freedom without order” could live out in the open without turning into smoke and shouting.

He told himself they would come back. This rebellion was a fever, not a cause. Noise. A few men with printing presses and loud mouths. The larger crowd would quiet down the moment winter did its work.

But right now, his eyes refocused from the daydream. The light grew dim. The glass fogged at the edges, as if someone had breathed on it from the other side. Odd, but no matter. It must be the snow coming. George turned from the window and walked to his desk.

The candle nearest him flickered, then steadied. The shadows in the room shifted and resettled themselves. Outside, the temperature dropped, the smell of snow in the air. A white Christmas for London, if the clouds obliged.

In the fireplace, a log cracked and sent up a shower of sparks. George watched them rise and wink, rise and wink, like small rebellions burning themselves to nothing against the indifferent air.

The clock on the mantel struck nine. Somewhere beyond the walls, a watchman sang the hour into the cold.

George gathered the dispatches. He placed them in the locked drawer where he kept such things, away from prying eyes and gossiping servants. He would read them again tomorrow. He would search once more for the explanation that was not in the dispatches.

The King prepared for bed. His evening routine varied little from one night to the next. He allowed his valet to help him undress. He said his prayers, more habit than devotion. He climbed into the vast bed with its heavy curtains, warming pans, accumulated weight of royal tradition.

He closed his eyes.

His sleep came and went, shallow and troubled. George tossed in the darkness, talking in his sleep. Words that his attendants, just outside the door, could not quite make out. The fire burned low. The candles, one by one, became a trail of smoke. The room, black.

Outside the window, the first flakes of snow began to fall on London. Gentle. Silent. It covered the courtyard where the plane leaf had landed. The city asleep in a blanket of white that looked almost like a fresh page.

He heard the clock strike midnight and keep ticking.

George, alone in his royal bed, surrounded by luxury and power that brought no comfort, found the wee small hours. The thin place where a man is neither awake nor asleep.

Some time later, the room, which had been empty, was suddenly not. A voice spoke out of the dark, as if it had been waiting for him.

Act I. The Ghost of Christmas Past

The voice came from nowhere and everywhere, the way a church bell finds you three streets away.

(inaudible) “George.”

“George.”

The King opened his eyes. The room was dark, but had not changed. The same heavy curtains and dying fire. Winter pressing against the windows. But this dark was different. Breath. Presence.

“Who’s there?” His voice came out steadier than he felt. A king’s training. “Guards…”

“They cannot hear you. Nor you them. We are between the ticks of the clock, you and I. In the space of memory.”

“There’s no one here.”

“There is,” the voice said, not unkindly. “Come. The night will not wait.”

George sat up. His eyes adjusted. There was no figure in the room. Only shadow, and within the shadow, a deeper shadow. Not a person. Breath on the air.

“What are you?”

“I am what was. The road behind you. The roads behind that road. The choices made before you drew breath.”

George felt his feet touch the cold floor, though he hadn’t moved. His hand reached for a robe that was not there, and he found himself in only his nightshirt, shivering slightly. A pale light gathered at the window. The glass, which should have been solid, yielded like water. He passed through it without feeling it pass, and then he was somewhere else entirely.

London. But not his London.

The streets were narrow and filthy. Choked with mud and offal and crowds that moved with dread. George had seen etchings of this time. He had read the history. But nothing had prepared him for the smell. Blood and smoke and fear. The smell coated his tongue.

“Sixteen forty-nine,” the voice said. “The thirtieth of January.”

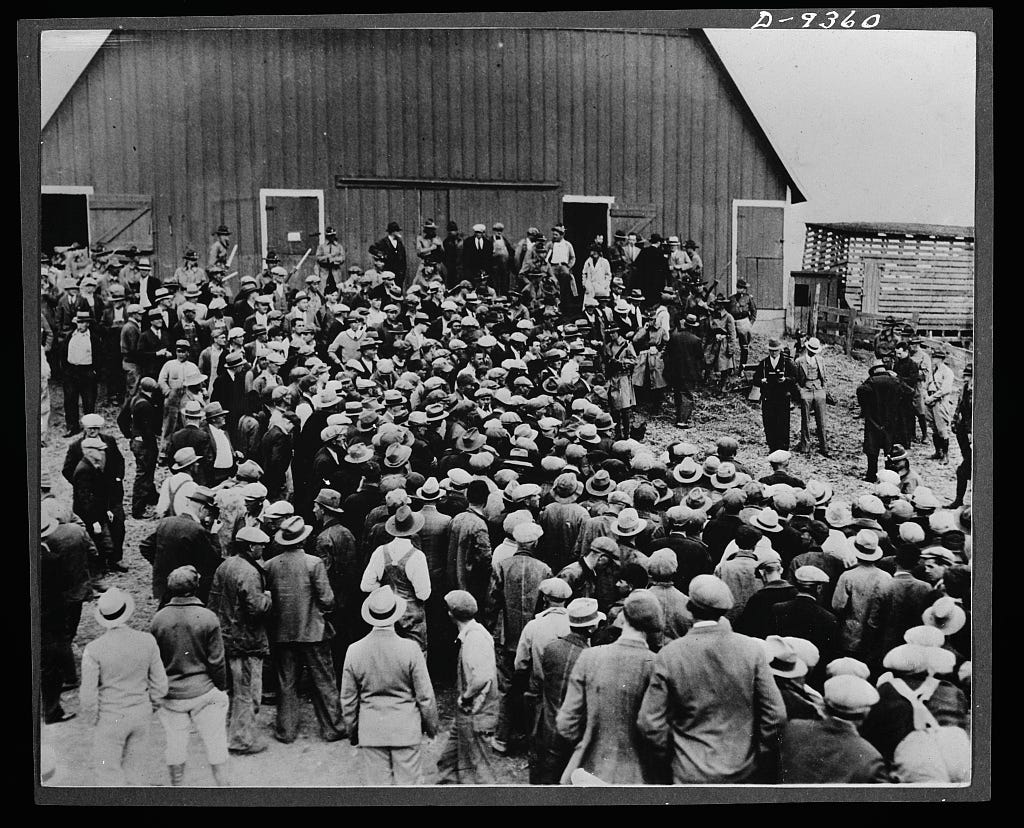

The crowd pressed toward a scaffold erected in front of the Banqueting House at Whitehall. George moved with them, unable to resist. A ghost among ghosts. A woman near him wept openly.

Through the crowd, George saw him.

King Charles I walked to the scaffold with the careful dignity of a man who had practiced this moment in his mind. His shirt was white. His hair, gray. His eyes found no one in the crowd, as if he had already departed for some place beyond their judgment.

“He wore two shirts,” the voice said softly. “So that he would not shiver in the cold. He wanted to look dignified. Strong.”

George’s throat tightened. He watched Charles kneel. He could not watch. He looked away.

But he heard it. The blade found its mark. Then another sound, a moan rising from the crowd. Thousands of throats releasing something that had no name. Not triumph. Not grief.

“Why do you show me this?” George whispered. “I know this story. Every king knows it.”

The ghost looked at him but did not speak.

Britain had torn itself apart in those years. Men who had been neighbors became enemies. Law vanished. Titles meant nothing. Thinkers had dreamed of a solution, a sovereign so absolute that chaos itself would bow before him. It