Should Every Generation be Richer than their Parents?

Description

Act I. The Golden Handcuffs

(SFX: Blizzard wind.)

January 1914. Highland Park, Michigan. Six degrees above zero.

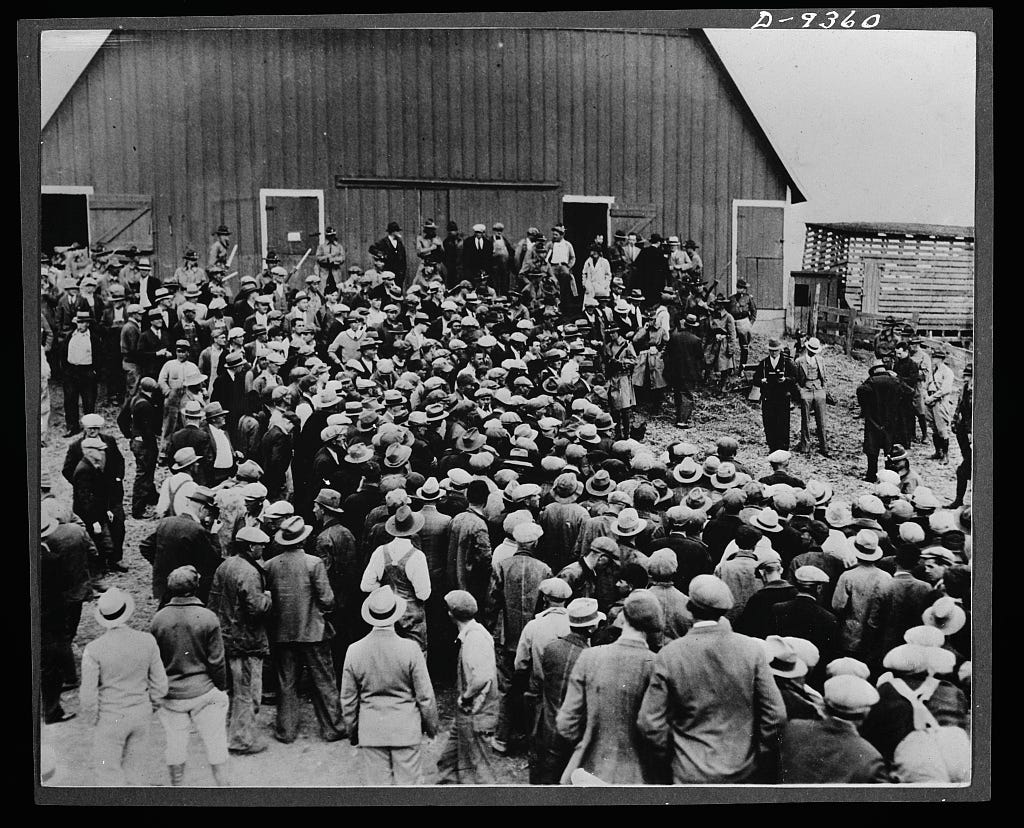

Ten thousand men press against the iron gates of the Ford Motor Company. Wool coats thin as paper. Broken boots stamping frozen mud. The guards inside are terrified. The mob is too large, so they turn the fire hoses on them. The water hits. Soaks through. Freezes instantly to ice on their coats.

The men don’t leave. They stand there, shivering, because a rumor has spread through the tenements of Detroit. A rumor that sounds like salvation:

Henry Ford is going to pay five dollars a day.

Understand what this means. At this moment in history, a factory man earns two dollars and thirty cents. He sleeps in a boarding house. Eats cabbage. Works ten hours until his back locks, then drinks away the pain at the saloon.

Ford is offering double for eight hours of work. An invitation for a laborer to live like a human being.

The men freezing at the gate think Henry Ford is their savior. They don’t know the whole truth.

Ford didn’t actually raise wages to five dollars. Base pay stayed at two-thirty-four. The rest, two dollars and sixty-six cents, he classified as “profit sharing.”

To get the profits, you had to pass inspection.

Ford created something called the Sociological Department. This wasn’t just Human Resources. This was a private intelligence agency. He hired 150 investigators. Gave them badges. Cars. And a mandate:

Go to the homes.

Here’s how it worked:

You finish your shift. Go home. Sit down for dinner.

A knock at the door. A man in a suit walks in, doesn’t ask permission. Opens your cupboards. Checks your bankbook. Questions your neighbors.

Does he drink? Is the house clean? Is he living with a woman who isn’t his wife?

If the investigator didn’t like what he saw, if your wife was working, if you bought a luxury before you bought property, he marked a red check on his clipboard. It tracked half the workforce. It pushed them into ‘Americanization’ classes to scrub away their accents and teach them how to be proper, obedient citizens.

Next payday? Two-thirty-four. The “profits” withheld. You’re on probation. Fix your life, or you’re fired.

Now imagine you’re one of those men.

You’ve been standing at the gate for three hours. Your coat is frozen stiff. Your children are hungry. Your wife is coughing blood because the tenement has no heat.

Ford’s man finally opens the gate. He hands you the paperwork. He explains the terms.

You read it. You understand it. You know what you’re trading. And you sign.

Because what kind of person wouldn’t? You resent the privacy invasion, but your children need a warm house. Your wife needs a doctor. You need to stop drinking yourself to death just to get through the week.

Ford is offering you a way out, and all it costs is permission. Permission for a stranger to walk through your door. Permission to judge how you live.

That’s the trade. Autonomy for comfort. Privacy for security.

And you take it. Who among us wouldn’t? Because we love our children more than we love our pride. We make the deal.

What they thought would make their children richer came with a cost they didn’t see yet.

The men took the deal. They stopped drinking. Cleaned their houses. Learned English. Bought the Model T. They became “materially better.” They had heat. Meat on the table. Shiny shoes.

We judge prosperity in income, consumption, and lifespan. By every measure, Ford’s workers won.

Their children grew up in warm houses. Went to school with full bellies. Had shoes without holes.

The workers looked at their fathers, men who died at fifty with nothing, and they knew they’d made the right choice. They’d bought their children a better life.

Ford’s productivity went up too, just like he planned.

In 1913, Ford had to hire 52,000 men just to keep 14,000 on the floor. Turnover was running at 370% a year. Training a new man cost the company roughly $100 in today’s money every time someone quit after a week. The $5 day, even with the strings attached, was still cheaper than that chaos. And it worked.

Absenteeism dropped. Turnover collapsed. It used to be 370% annually, but fell to 16%. Workers showed up sober. Worked faster. Made fewer mistakes.

Productivity went up. Way up. In 1914, it took 12 hours and 8 minutes to assemble a Model T. By 1920? One hour and 33 minutes.

Ford didn’t pay five dollars a day out of charity. He paid it because it was cheaper than chaos. A sober, stable, surveilled workforce was more profitable than a desperate, drunk, transient one. He cut turnover costs and saved $100M annually in today’s dollars. Profits doubled from 1914 to 1916. Every boss in America took notes. They called it ‘Welfare Capitalism.’ It sounded generous. It was actually a leash.

The inspections weren’t about morality. They were about profitability. Ford’s workers paid for their own compliance. He didn’t force them. He bought them. He made submission profitable.

The men took the deal. They quit the saloons. They scrubbed their floors. They opened savings accounts. They learned English in Ford’s mandatory classes. They bought Model Ts on installment, often from the same company that was watching them. Their kids went to school with shoes that didn’t leak.

They didn’t clean their houses because he ordered it. They wanted the money. They didn’t stop drinking because he banned it. They couldn’t afford to lose the profit-share. They invited the inspector in because their children were counting on it.

Other companies watched the numbers and copied pieces of it. General Electric, International Harvester, and dozens more launched profit-sharing plans. “Welfare capitalism” became the buzzword of the 1920s. An effort to control workers while, at the same time, giving the state no excuse to cross the property line.

But once you accept that the price of a good life is constant inspection, you can’t unmake the deal. It becomes normal. The cost of living well. You trade your autonomy for comfort.

Ford called this the Five Dollar Day. He called it profit-sharing. We still call it the birth of the Middle Class. We hold the products of the plans in high regard. Profit-sharing bonuses. Retirement plans. Medical services.

What Ford proved, accidentally or not, is that he could get a huge chunk of the population to trade a very specific kind of liberty, the privacy in your own home and freedom from moral judgment by your employer, for material goods. And most of us would consider it a bargain.

Pensions, profit-sharing, and the company doctor were born inside a surveillance program. In the 1920s, with no regulation, these tools controlled workers.

We still call them benefits. We just stopped noticing the handcuffs.

Act II. The Fugitive and The Tenant

Here’s the question that should bother us: Ford’s workers got the money. The cars. The warm houses. Did they actually get richer?

To answer that, we need to go back to the old definition of property. Not the modern one, based on the number in your bank account. The old one. The one that defined what it meant to be free before anyone ever heard of an assembly line.

Back to a fugitive on the run.

1683. London. Past midnight.

A man is packing by candlelight. One candle. Any more would draw attention from the street.

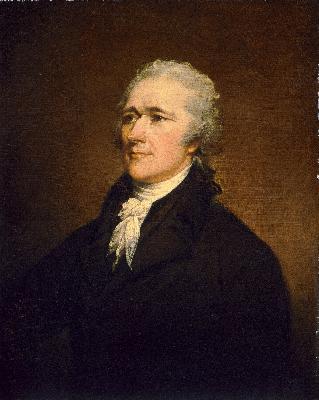

His name is John Locke. Fifty-one years old. A philosopher, not a soldier. He’s spent his life in libraries, writing treatises on medicine and education that offended no one. But now his hands won’t stop shaking.

He’s deciding what to bring. What to leave. What might get him killed if they search his bags.

At the bottom of his trunk, wrapped in oilcloth, sits his life’s crown jewel. A manuscript. Two hundred pages arguing that kings rule by consent, not by God. That when a king becomes a tyrant, the people have the right to remove him. By force if necessary.

If the King’s men find it, they won’t need a trial. Because King Charles II remembers.

Charles was eighteen years old when Parliament put his father on trial. Eighteen when they declared that the people had the right to judge their king. Eighteen when they marched Charles I to a scaffold outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall, made him kneel, and took his head off with an axe while a crowd watched.

Charles II spent the next eleven years in e