Who Can the President Fire?

Description

2025. The president fires an FTC commissioner before her term is up. The statute says he can’t without cause. He does it anyway. Now the Supreme Court has to decide whether ninety years of precedent was real law, or a bluff.

Act I. The Wager

[SFX: casino room, cards dealt, chips stacked, ice clinking in glasses]

Players stare at each other across a poker table. Four cards are up. One card is face down. The last card decides everything, but nobody gets to see it until somebody commits.

You can stare at the felt and pretend time is on your side. But the cost of waiting goes up anyway. You have to put in a bet to keep playing, and that bet keeps getting bigger. The pot grows. The pressure rises. Sooner or later, you have to act with incomplete information.

New York City. Late Spring, 1789.

George Washington took the oath on April 30. He is the first President of the United States. He has duties. He has no government.

No State Department. No Treasury. No War Department. No one to answer a foreign minister or respond to a crisis. The executive branch exists on paper. In reality, it is one man in a rented house with a small staff and a pile of unanswered letters.

The Constitution is eight months old. The ink is barely dry. And the world is not waiting.

The British still occupy forts on American soil. Forts they agreed to vacate six years ago. Native attacks keep coming from those regions. Plenty of Americans suspect the British, but Washington has no department to respond with.

Spain has closed the Mississippi River to American trade. Western settlers are talking about leaving the union. Diplomacy might help. Threats might help. But there is no one to conduct diplomacy. The president cannot do everything himself.

American merchant ships are being seized in the Mediterranean. Algiers declared war on the United States four years ago. Sailors are chained in North African prisons, waiting for a ransom that cannot come because we have no Treasury and no Navy.

The pot is already enormous. The blinds are rising. And Congress has a problem.

The Constitution gives the president the power to appoint officers “by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.”

It says nothing about firing them.

Nothing.

That silence is not calm. It’s cards sliding out. Sideways glances. Men looking across the table, trying to decide what the other man is holding.

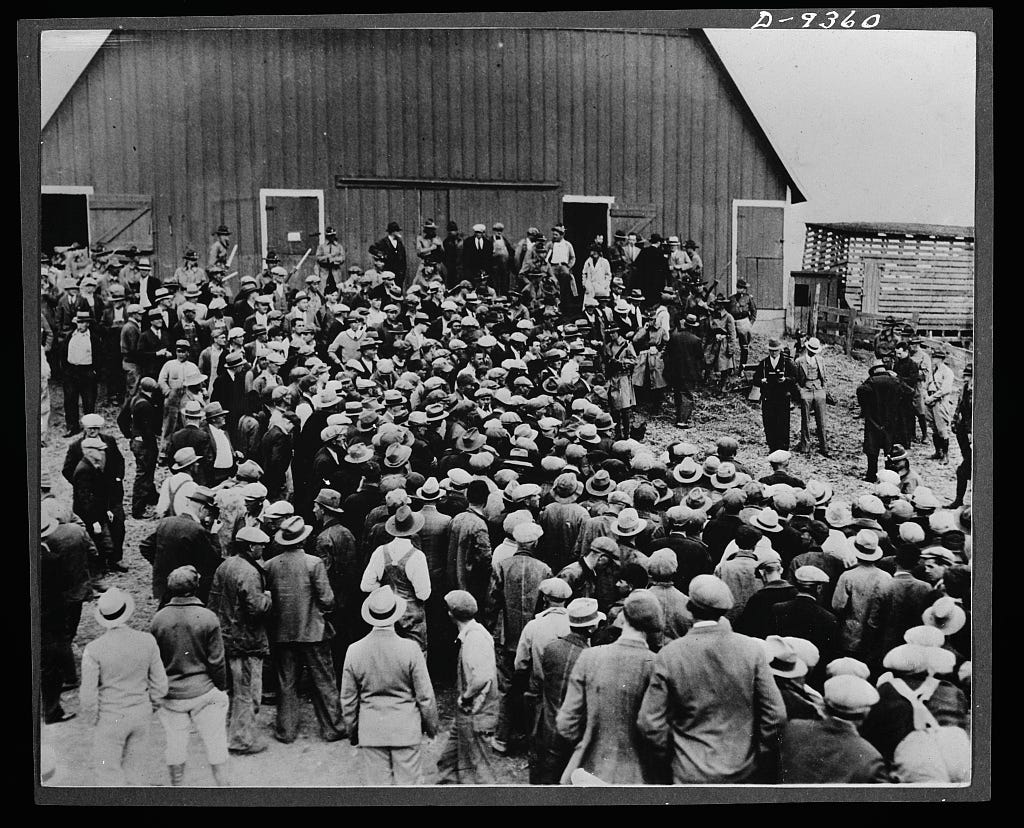

Sixty-five men crowd into Federal Hall on Wall Street. A repurposed city building that still smells like fresh paint. May turns to June. The weather thickens. No ventilation worth mentioning. Wool coats. Wigs. Windows that don’t open properly. Paper everywhere. Quills scratching. Men sweating through their shirts while arguing about the shape of executive power.

They have to build a working government, but the game is already underway. The cards are on the felt. The pot is growing. And they’re still arguing over who gets to deal, who sets the rules, and who can push a man out of his seat.

The question before the House is simple to ask and impossible to answer:

Who can fire a cabinet secretary?

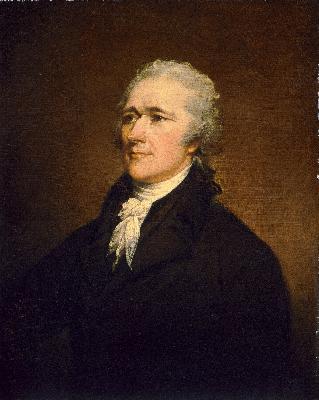

James Madison rises to make a motion.

He is thirty-eight years old. A hundred forty pounds soaking wet. He speaks so softly that reporters lean forward to hear him. He is brilliant, but he has never seen combat. He has never led troops. He spent the Revolution in the Virginia legislature, arguing about paper while other men bled.

But Madison wrote the Constitution. He wrote most of The Federalist Papers defending it. He has thought more carefully about the structure of American government than anyone alive. When Madison speaks, the room listens.

His motion concerns the Department of Foreign Affairs. A department that does not yet exist. A secretary who has not been named. He is writing the job description for a position that is still an idea on paper.

Madison proposes one line:

He says that the secretary shall be “appointed by the president, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate; and to be removable by the president.”

Four words. Nine syllables. “Removable by the president.”

The room erupts in disagreement.

They can see the future in that sentence. A future president. A future fight. A future Congress trying to bind a president’s hands. They are not arguing about today. They are arguing about every president and every Congress that will ever follow.

And they are terrified. But not of the same thing.

To understand why the room erupts, you have to understand the ghost in it. That ghost is King George III.

Theodorick Bland commanded cavalry in the Revolution. James Jackson of Georgia fought at Cowpens, Augusta, Savannah. Hand to hand when it came to that. Jackson fought twenty-three duels in his lifetime. He settled disagreements with pistols. When he stood up to speak, men listened because they knew what he was capable of.

Elbridge Gerry was asleep at the Menotomy Tavern on the night of April 18, 1775. The night Paul Revere rode. British troops marched past his window toward Concord. The weapons they were marching to seize were weapons Gerry had put there. His roommate during the siege of Boston was Joseph Warren. Warren died at Bunker Hill with a British bullet in his skull.

On and on. The room was full of men who bled for independence. They sent their sons to bleed. They watched friends die at Brandywine, at Germantown, at the frozen hell of Valley Forge.

The Declaration of Independence was thirteen years old. It was a list of crimes committed by a king who answered to no one. These men had signed it. Some had nearly died for it.

Now, James Madison, who spent the war arguing about paper, stands before them and proposes giving one man the power to fire anyone in the executive branch.

To some of them, it sounds like the first step toward a throne.

Underneath that knife’s edge urgency, they are dueling with words while playing this game of American poker. Uncertainty. Ambiguity. They’re all fearful, but not of the same thing.

One man hears “removable by the president” and sees a king. Total loyalty. Total control. Every officer knowing he serves at the president’s pleasure. Every officer afraid to disagree. William Loughton Smith of South Carolina places his bet here. He points to the Constitution: the only removal it mentions is impeachment. If you start inventing powers out of silence, you are training future presidents to do the same.

Theodorick Bland of Virginia throws in chips next. He hears “removable by the president” and sees the Senate being erased. The Constitution says the president appoints “by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.” The Senate has a role. Would you let a man hire but not fire? Strip the Senate of removal, and you strip the bridle from the horse.

Roger Sherman of Connecticut adds to the pot. He hears “removable by the president” and sees chaos. Drift. Officers who answer to no one because no one has clear authority. He says Congress creates these offices, Congress sets the terms, Congress can decide. The Constitution doesn’t give removal power to anyone specifically. So Congress fills the gap.

And then there is Madison.

Madison has watched legislatures become tyrants.

State assemblies under the Articles of Confederation printed worthless money. Exposed private contracts to public violation. Trampled the rights of minorities, religious dissenters, anyone without the votes to protect themselves. In Rhode Island, the legislature printed currency to pay off debts, and the creditors fled the state.

Kings were dangerous. Madison knows that. But legislatures were also dangerous. They claimed to speak for the people. They wrapped their tyranny in democratic legitimacy. And they could do it faster than any king because they did not have to pretend to be anything other than the majority.

Madison fears Congress more than he fears the president.

He could not fo