Should Old Acquaintance Be Forgot?

Description

[SFX: Solo Guitar playing Auld Lang Syne]

Should old acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind? Should old acquaintance be forgot, and the days of long ago?

We’ve forgotten the meaning of the song playing in the background when we toast on New Year’s Eve.

Let’s remember.

Back to Ulysses S. Grant. He couldn’t hear music. Not wouldn’t. Couldn’t. And the most important moment of his life would be defined by a song.

Act I. The Man Who Couldn’t Hear Music

Washington, D.C., March 8, 1864.

Ulysses S. Grant walks into Willard’s Hotel. Forty-one years old. Filthy from four days on a train. He is the most famous man in America, and nobody recognizes him.

The hotel is famous. Senators swagger and generals preen across its thick, patterned carpet. Gas lamps throw a yellow light that doesn’t reach the corners, so faces drift in and out of shadow. Furniture packed in tight clusters. Little tables and chairs arranged for waiting, not resting, crowded by hats, gloves, and half-empty whiskey glasses.

The desk clerk eyes Grant as he crosses the room. Mud-spattered coat. Rumpled uniform. No entourage. His boots are caked with Tennessee mud, red clay flaking onto the carpet. The clerk judges his station in life and says there’s nothing available but a cramped room in the garret. The attic.

Grant takes it. He signs the register in a plain hand: U.S. Grant & Son, Galena, Illinois.

The clerk reads the signature. His face goes white. Suddenly, the Presidential Suite, the rooms Abraham Lincoln occupied before his inauguration, is available after all.

Grant declines. The garret is fine.

This is Grant. No drama. No ceremony. And something even more peculiar.

Ulysses S. Grant cannot hear music.

It’s not that Grant “doesn’t like music.” Not that he “has no taste for music.”

When a band plays, Grant hears only noise. A choir sings, Grant hears chaos. Marches. Hymns. Sentimental ballads. They all register the same way. Pots banging. Wagons rattling. Nothing more.

He once described it this way: “I know only two tunes. One of them is ‘Yankee Doodle,’ and the other isn’t.”

People took this as a joke. A curmudgeon’s quip. But Grant wasn’t joking. He could recognize “Yankee Doodle” because it came wrapped in parades and flags and ritual. He knew it by context, not by sound. Every other tune in the world was the same to him. Noise.

Doctors today call it congenital amusia. The brain can’t process pitch. Each note disappears as soon as it sounds. The pattern never forms.

In 1864, they had no name for it. Grant just lived with it. He never explained why music meant nothing to him. But other officers noticed he would leave the room when bands played. He didn’t grimace. He didn’t complain.

He just drifted away.

Back to Willard’s Hotel. That evening, Grant cleans up and goes down to dinner.

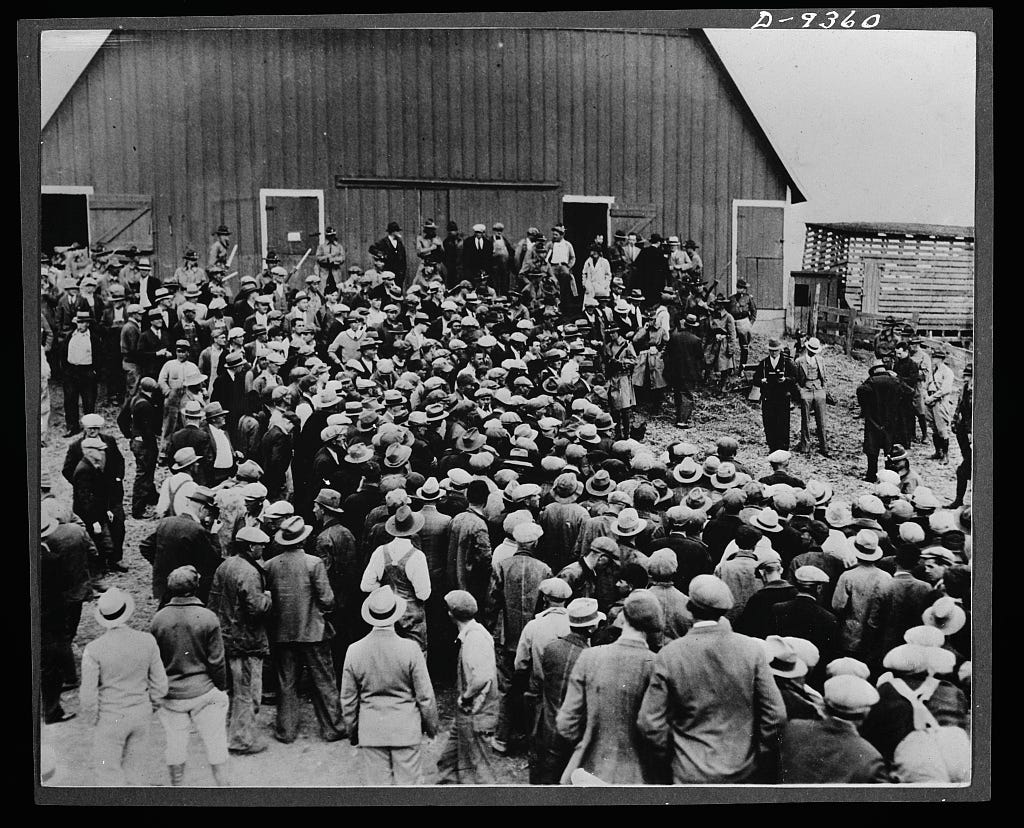

He and his thirteen-year-old son Fred take a small table in the crowded dining room. He orders. Within minutes, someone recognizes him. A congressman stands and bellows across the room: “Ladies and gentlemen! The hero of Donelson, of Vicksburg, and of Chattanooga is among us! I propose the health of Lieutenant General Grant!”

The chant begins. Grant. Grant. Grant.

The diners surge toward his table. He stands awkwardly, bows, tries to eat, gives up. The mob presses closer. For three quarters of an hour, he shakes hands with strangers. Finally, he escapes to his room. He never finishes the meal.

Later that night, politicians appear at his door. They rush him through the rain to the White House, where President Lincoln is holding his weekly reception. The East Room is packed. Hundreds of Washington society figures, all hoping to glimpse the western hero.

The crowd parts. Grant walks through.

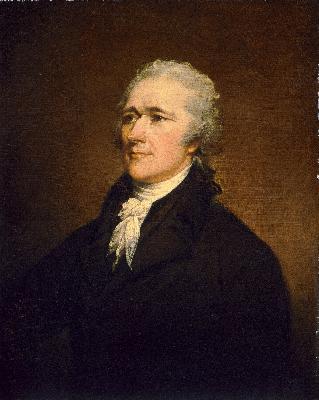

Abraham Lincoln stands waiting. They have never met, though they are now the two most famous men in the country. Lincoln is a head taller, six foot four. Grant is five eight.

Lincoln steps forward, smiling, and extends his hand. “Why, here is General Grant. I am most delighted to see you, General.”

Grant answers with a nod and a few words so quiet Lincoln has to lean in.

The Union Army of Grant’s time was saturated in music.

More than 500 regimental bands. Drummers and fifers at every unit. Bugles structured the entire day. Reveille. Assembly. Mess call. Sick call. Taps. Music lifted spirits. Stiffened resolve. Gave orders.

And Grant was deaf to all of it.

He understood music strategically. He watched what it did to other people. Saw men weep at certain songs. Stiffen at others. The way someone colorblind might notice how others respond to a sunrise.

After West Point, Grant was a young lieutenant in Mexico. His regiment’s band raised morale, but it needed funding. Bands were absurdly expensive, and politicians loved them. Congress would argue over rifles, but bands needed paid.

So Grant ordered the unit’s daily rations in flour instead of bread, at significant savings. Then he rented a bakery. Hired bakers. Sold fresh bread through a contract he’d arranged with the army’s chief commissary. The profit went to music he could not hear.

This is who Grant was. Practical. Unsentimental. Results-oriented.

Sentiment in the Union Army was a liability.

The next morning, Lincoln hands Grant his commission. Lieutenant General of the United States Army. The highest rank in the army.

Grant is now in command of all Union forces. More than half a million men.

The war is in its fourth year. Two hundred and fifty thousand Union soldiers are already dead or wounded, with little progress to show. Every general Lincoln has appointed to fight Robert E. Lee has failed. They engage. Suffer losses. Retreat north to regroup. Then they do it again.

The reality is that the Civil War is a war of attrition. Wars of attrition aren’t clever. Force meets force until one side can no longer continue.

To achieve the nation’s ends, Lincoln needs someone different. Someone who doesn’t retreat.

Days after the ceremony, Lincoln’s assistant asks what kind of general Grant will be. Lincoln thinks for a moment.

“Grant is the first general I’ve had. He doesn’t ask me to approve his plans and take responsibility for them. He hasn’t told me what his plans are. I don’t know, and I don’t want to know. I’m glad to find a man who can go ahead without me.”

Lincoln pauses, then adds.

“Wherever he is, Grant makes things git.”

The Army medical corps had made it official. They called it nostalgia.

Not nostalgia like we use the word today, a warm feeling about the past. Nostalgia as a diagnosis. A disease. A killer.

Union surgeons wrote down thousands of cases. Men who wasted away, moaning for home. The symptoms look like what we would now call severe depression. Insomnia. Loss of appetite. Withdrawal. Despair. In the worst cases, they just stopped. Refused food. Refused nursing. Died.

The army identified a trigger. Music.

Sentimental songs did it. Ballads about home. Mothers. Sweethearts left behind. The most dangerous song in camp was “Home, Sweet Home.” Men heard it and broke. So officers barred bands from playing it.

Songs like “Auld Lang Syne” carried the same danger. Remembering friends from long ago. Remembering home. Memory as a weapon turned inward. The song that made you weep for the past was the song that could kill you in the present.

Grant would have understood that logic perfectly.

Now Grant is in Washington, his new commission in hand. Culpeper, Virginia waits, his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac. Robert E. Lee waits, fifty miles south.

Grant lays out his philosophy in a single sentence: “The art of war is simple enough. Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike him as hard as you can, and keep moving on.”

No sentiment. No retreat. Attrition.

Act II: The Overland Campaign

The Wilderness, Virginia. May 5, 1864.

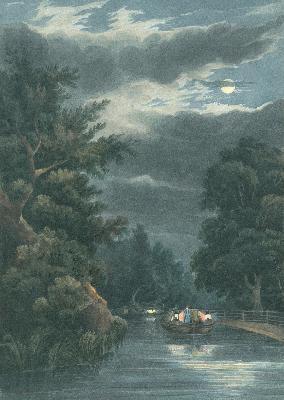

Grant crosses the Rapidan River at midnight. Sixty thousand men. Pontoon bridges sway in the dark. By dawn, the Army of the Potomac is deep inside a seventy square mile tangle of vines and second growth so dense the soldiers call it, simply, ‘the Wilderness.’

The Union Army was routed here one year earlier. Lee’s bold flanking maneuver sent them running. The bones of the dead from that battle lie in the undergrowth. Skulls grin up at passing troops. The new soldiers try not to look.

Grant’s plan is simple: move fast and get through the forest before Lee can react. Fight in open country where Union artillery and superior numbers can be decisive.

Lee reacts faster.

By midmorning, the Wilderness becomes a killing ground that neutralizes every Union advantage.

Soldiers couldn’t see twenty yards in any direction. Brush so thick you lose sight of the man next to you. Smoke from musket fire fills the gaps between trees. You only see the enemy by the muzzle flash when he shoots at you.

There is no battle line. No coordination. No grand strategy. Only chaos. Small groups of men stumbling