Don't Shoot, Just Think!

Description

[Before we start, I want to let you know about my new zine, Cloudless. It’s now available, and you can pick it up here.]

The narrow dirt road straddled the Idaho/Washington border with late spring wheat fields, their stalks nearly to my knees, growing on either side. I stopped the car on a hill and waited for the dust to settle so that I might see the scene behind me in my rearview mirror.

I stepped onto the road, grabbing my camera and checking to see again what I had loaded. The road ran through a small cut into the hill, with steep enbankments rising above on either side. I scrambled to the top of one and saw the green wheat undulating like waves on a vast and uneven ocean.

The hill I was on rolled its way to a small valley and other hills rising in the middle distance. An old barn stood in the valley, its wooden walls decaying and its tin roof patched, but intact. Light clouds dotted the sky.

I raised the camera, took the photo, and slid back down to the road. This entire encounter took maybe thirty seconds. I stumbled into a lovely composition, and the photo nearly took itself. I was back in the car and driving to the next picture.

Just how much thought I put into this photo, I couldn’t tell you. I know a good composition when I see one. I saw one and took the photo. It’s not that I didn’t think, it’s not that I just shot. I quickly scraped together whatever experience and foreknowledge I had, saw the photo before me, and took the picture.

Lomography

There is a film company called Lomography that markets its rebranded films to photographers who want a certain lo-fi look. It plays well on nostalgia, and they’ve managed to turn the memories of grandma’s photo albums into a thriving business.

On each roll of film they produce, they’ve printed their slogan: Don’t Think - Just Shoot! There is something mildly philosophical about this. I understand immediately what they want us to believe they’re saying. “Don’t overthink the photograph, go with your gut, shoot it!”

Of course, what they’re actually saying is “buy more film.” After all, they are a company whose priority is the bottom line. The more film we shoot, the more film we buy. And the more film we shoot without thinking, the more film we blow through like a mid-80s wedding photographer.

I can’t stress enough how bad this advice is. The advice is as bad as the faith of Lomography’s argument. It is only made worse by how obvious and brazen a cover it is.

And still, on this trip, I brought along a film Lomography called Potsdam. Before the rebranding, the film was made by German motion picture film manufacturer ORWO, which called it UN54. I used to buy it in bulk back in my 35mm days. The only way to acquire it now in medium format is to buy it as Potsdam from Lomography.

I love how this emulsion handles shadows, how inky dark it can be. There is a contrast to this film that you can ply with a yellow filter, or even red. I would shoot this film more, and might even use it regularly if not for Lomography’s lack of quality control. But more on that later.

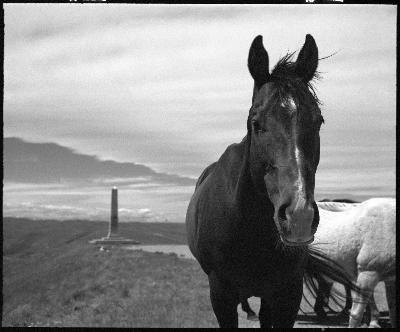

Cows

I often find myself driving through range land, where cows and sometimes sheep roam free. An awareness of this is necessary when I’m driving, and caution is always in order. A few years back, while driving near the Missouri River in Montana, I was surrounded by cows with their young bulls. One of the bulls spooked and, rather than running away from my car, ran into the front quarter panel, putting a huge dent in it.

I stopped to see if he was okay - he was. And then I called my insurance company to explain that a cow had hit my car. “You hit a cow?” she asked. “No,” I replied, “other way around.”

Cows are usually skittish and fearful of us. It’s no wonder the hell we put them through. Taking their photo is something that almost never happens for me. The car already frightens them, and then when a human emerges from this metal cage, it’s basically the end times.

But along a Summer Road I’ve photographed before, I came across cows and heifers on both sides of the road. They were behind fences, and there were no young and frightened bulls to be seen.

The older cows were immediately uneasy, but the heifers, maybe a year old, were curious. Their eyes met mine, and they stood watching me. Another walked closer to get a better look.

I slowly went for my camera and began talking to them in a soft voice. I have no idea if this mattered, but it put me at ease. I walked from the road, over a small ditch, and into the grass where the barbed wire fence was strung, separating the cows from the road.

They stood, just looking, though I could see the clouds of hesitation and anxiety building behind their eyes. I lifted the camera and focused. This is usually as far as I’ll get with cows. At this point, they’re taking no chances and running away, often creating a mini-stampede.

This time, however, they just watched. They looked into the camera. There were three of them - two younger, one older. I was afraid that the loud click of the shutter and mirror slap of the Mamiya RB67 might scare them away, but even that hardly registered.

I took several photos of the trio and another of a mother and calf, who also cooperated, though with much more apprehension.

I had to work quickly. I had no idea how long my luck would hold, how long the cows would tolerate this strange event happening before them. I had to “just shoot,” worried that I might miss the opportunity. But I never stopped thinking, I never ceased calculating the odds of getting just one more photo.

In the end, that wouldn’t have mattered to Lomography (whose film, Potsdam, I was shooting). I quickly finished the roll and loaded another. They don’t really care if you think or not, they just want you to shoot more. And I did. Then, with the next roll of Potsdam ready to go, I returned to the car, grateful that the cows were brave girls. The boys could certainly learn some lessons.

The Worst Question Ever

Back in the days of the previous podcast, I interviewed dozens of photographers. Through all of that, there was one question I never asked, one question that nearly every other film photography podcast asked first: “Why do you choose to shoot film?”

It’s not that it’s necessarily a bad question. It’s just that nearly every film photographer answers it the same way - some variation of: “I shoot film because it makes me slow down.”

This answer, like the photographers answering, comes at the question from the aspect of a former digital photographer who thoughtlessly shot everything as quickly as they could.

It’s understandable; that’s how digital photography was marketed. With film, you had 36 exposures at most before you had to change rolls. With digital, you’ve got hundreds.

However, these are two different issues: one of speed and one of capacity. They’re not actually related at all.

The push for faster photo-taking wasn’t invented with digital cameras. All through the 70s and 80s, film camera manufacturers pushed how quick and easy their new cameras were. From the motorized backs for medium format to the point & shoot 35mms, how quickly we could blow through frames was a huge selling point.

Wheat

There are small dirt roads that are rarely driven by anyone but farmers to and from their tractors parked on the edge of their fields. But I drive them. There are seldom homes along them, no businesses, rarely even barns. But here, the roads rise and fall with the land. Only slightly graded (maybe once in the springtime), these Summer Roads offer us the closest feel we’ve got to the roads of the territorial days, the days before the car.

As I bounced along one, driving west with the morning sun at my back, I was again between wheat fields. The road was straight and level, though a small ridge rose beyond. In the middle of the road, as if planted on purpose, grew a small and struggling stalk of wheat. Its leaves wrinkled unshaded under the sun, yet still several spikes of grains grew in seeming defiance.

It was not purposely planted here. It likely fell accidentally from a seeder and somehow managed to take root. Standing alone in the center of the road, the stalk of the plant was missed by the tires of tractors and trucks over the months it had been growing. I could have driven over it, not harming it in the slightest.

Instead, I stopped. I sat there looking at the stalk, wondering how I could photograph it. I don’t know how long I considered the scene. Was it even worth it? Before very long, I grabbed my camera from the back seat and walked up to the plant. I’d probably be the only car on this road all day. I had time.

Looking over this stunted stalk of wheat, I consciously mulled the decisions between color and black & white, between a wide aperture and narrow. Did I feel it should be horizontal or vertical? I know I wished for a lens wider than the 90mm. It wouldn’t be the first nor last time that thought crossed my mind.

The light was perfect. The sun was high enough so that I might not cast a shadow onto the plant, but low enough to bring definition and texture to the leaves and seeds. I knew I had time, so I took it.

Crouching, knees now in the dirt of the road, I took my first shot - a simple black & white picture with the wheat in focus. I decided to open the aperture and held myself steady to not miss focus. I knew the fields on either side of the road would fall to a mostly ill-defined blur, but the road and the tread from the trucks driving through before me would show. The story of just how this little plant was surviving would be