Stop Using Entity Framework Like This

Description

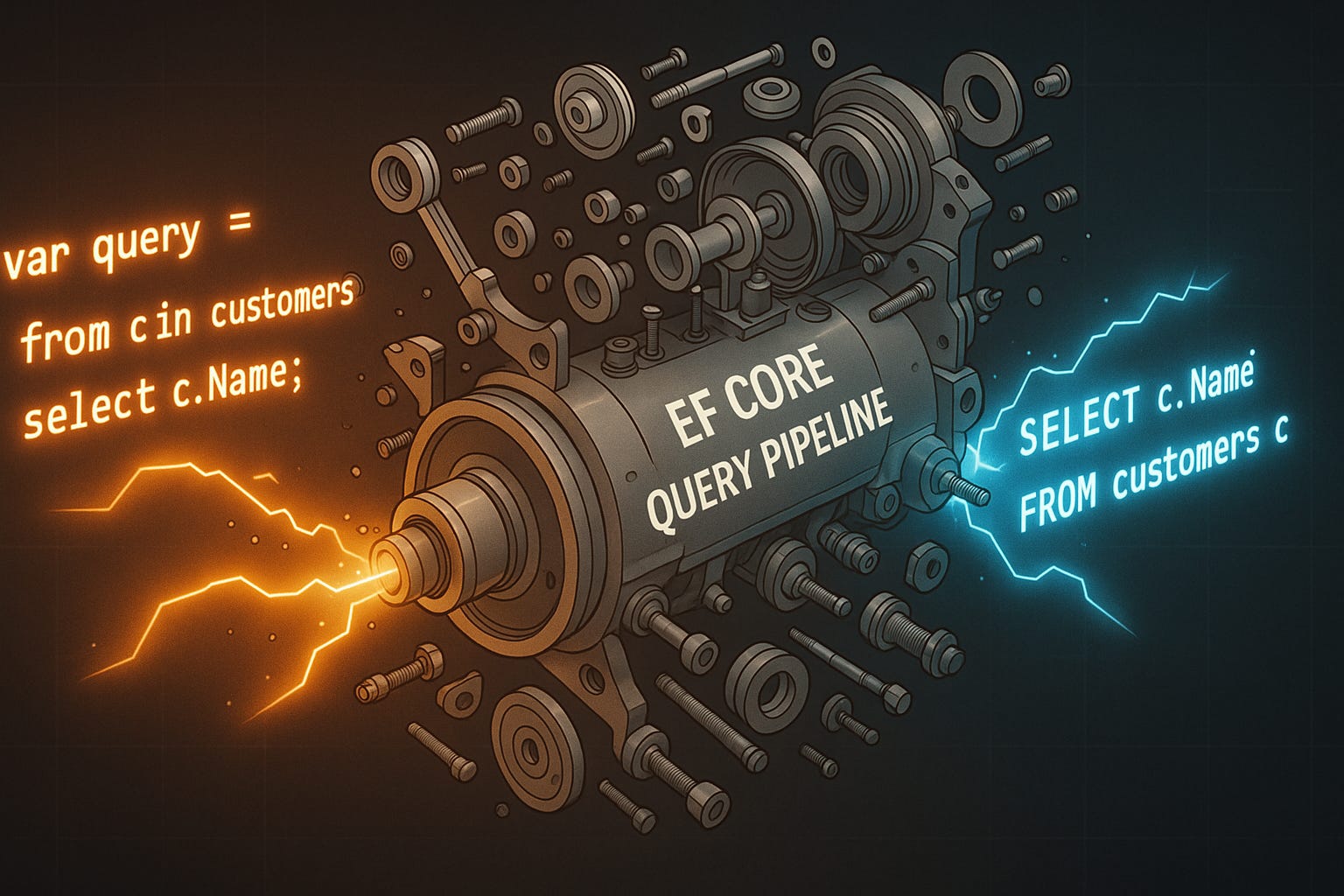

If you’re using Entity Framework only to mirror your database tables into DTOs, you’re missing most of what it can actually do. That’s like buying an electric car and never driving it—just plugging your phone into the charger. No wonder so many developers end up frustrated, or decide EF is too heavy and switch to a micro-ORM. Here’s the thing: EF works best when you use it to persist meaningful objects instead of treating it as a table-to-class generator. In this podcast, I’ll show you three things: a quick before-and-after refactor, the EF features you should focus on—like navigation properties, owned types, and fluent API—and clear signs that your code smells like a DTO factory. And when we unpack why so many projects fall into this pattern, you’ll see why EF often gets blamed for problems it didn’t actually cause.

The Illusion of Simplicity

This is where the illusion of simplicity comes in. At first glance, scaffolding database tables straight into entity classes feels like the fastest way forward. You create a table, EF generates a matching class, and suddenly your `Customer` table looks like a neat `Customer` object in C#. One row equals one object—it feels predictable, even elegant. In many projects I’ve seen, that shortcut is adopted because it looks like the most “practical” way to get started. But here’s the catch: those classes end up acting as little more than DTOs. They hold properties, maybe a navigation property or two, but no meaningful behavior. Things like calculating an order total, validating a business rule, or checking a customer’s eligibility for a discount all get pushed out to controllers, services, or one-off helper utilities. Later I’ll show you how to spot this quickly in your own code—pause and check whether your entities have any methods beyond property getters. If the answer is no, that’s a red flag. The result is a codebase made up of table-shaped classes with no intelligence, while the real business logic gets scattered across layers that were never designed to carry it. I’ve seen teams end up with dozens, even hundreds, of hollow entities shuttled around as storage shells. Over time, it doesn’t feel simple anymore. You add a business rule, and now you’re diffing through service classes and controllers, hoping you don’t break an existing workflow. Queries return data stuffed with unnecessary columns, because the “model” is locked into mirroring the database instead of expressing intent. At that point EF feels bloated, as if you’re dragging along a heavy framework just to do the job a micro-ORM could do in fewer lines of code. And that’s where frustration takes hold—because EF never set out to be just a glorified mapper. Reducing it to that role is like carrying a Swiss Army knife everywhere and only using the toothpick: you bear the weight of the whole tool without ever using what makes it powerful. The mini takeaway is this: the pain doesn’t come from EF being too complex, it comes from using it in a way it wasn’t designed for. Treated as a table copier, EF actively clutters the architecture and creates a false sense of simplicity that later unravels. Treated as a persistence layer for your domain model, EF’s features—like navigation properties, owned types, and the fluent API—start to click into place and actually reduce effort in the long run. But once this illusion sets in, many teams start looking elsewhere for relief. The common story goes: "EF is too heavy. Let’s use something lighter." And on paper, the alternative looks straightforward, even appealing.

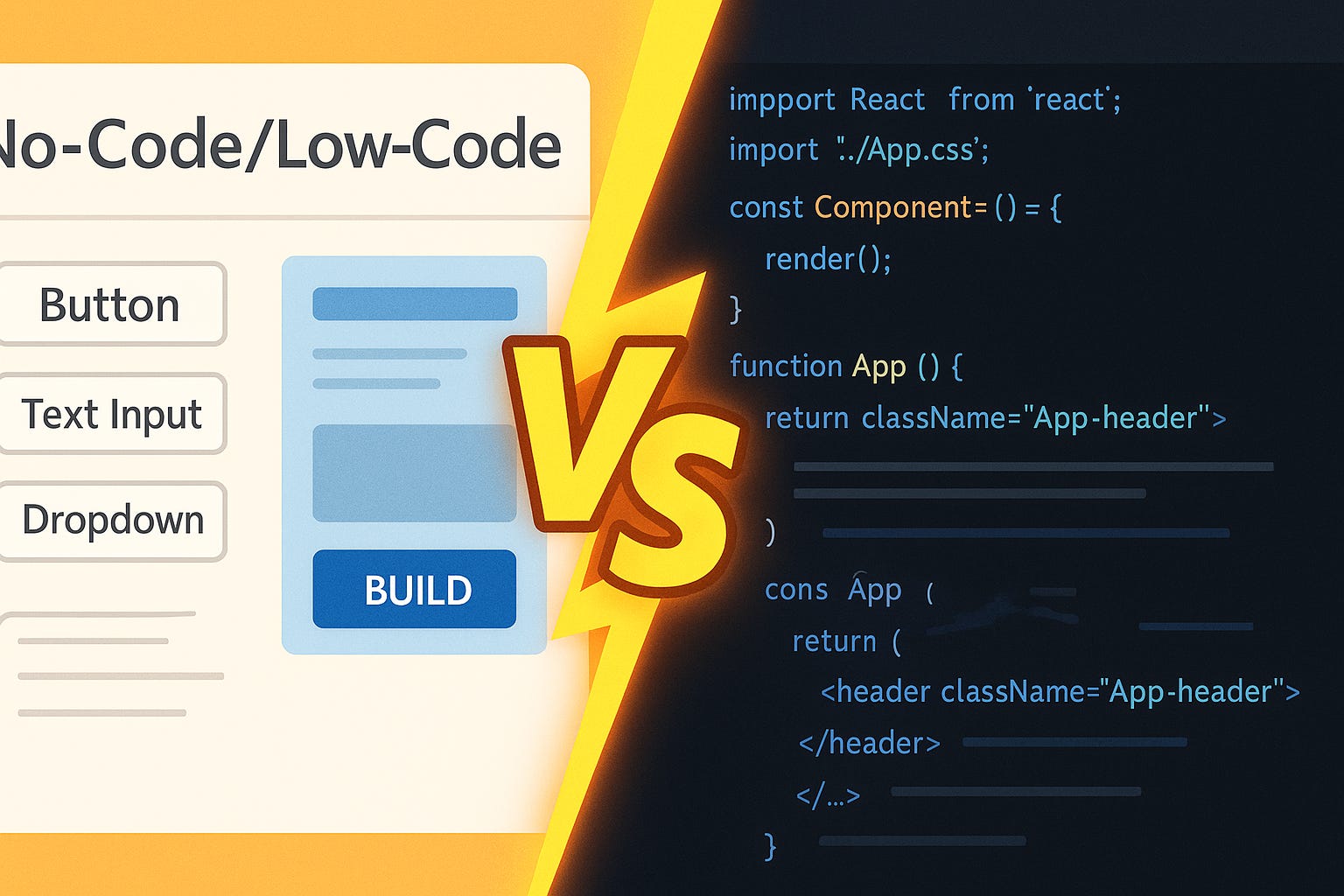

The Micro-ORM Mirage

A common reaction when EF starts to feel heavy is to reach for a micro-ORM. From experience, this option can feel faster and a lot more transparent for simple querying. Micro-ORMs are often pitched as lean tools: lightweight, minimal overhead, and giving you SQL directly under your control. After dealing with EF’s configuration layers or the way it sometimes returns more columns than you wanted, the promise of small and efficient is hard to ignore. At first glance, the logic seems sound: why use a full framework when you just want quick data access? That appeal fits with how many developers start out. Long before EF, we learned to write straight SQL. Writing a SELECT statement feels intuitive. Plugging that same SQL string into a micro-ORM and binding the result to a plain object feels natural, almost comfortable. The feedback loop is fast—you see the rows, you map them, and nothing unexpected is happening behind the scenes. Performance numbers in basic tests back up the feeling. Queries run quickly, the generated code looks straightforward, and compared to EF’s expression trees and navigation handling, micro-ORMs feel refreshingly direct. It’s no surprise many teams walk away thinking EF is overcomplicated. But the simplicity carries hidden costs that don’t appear right away. EF didn’t accumulate features by mistake. It addresses a set of recurring problems that larger applications inevitably face: managing relationships between entities, handling concurrency issues, keeping schema changes in sync, and tracking object state across a unit of work. Each of these gaps shows up sooner than expected once you move past basic CRUD. With a micro-ORM, you often end up writing your own change tracking, your own mapping conventions, or a collection of repositories filled with boilerplate. In practice, the time saved upfront starts leaking away later when the system evolves. One clear example is working with related entities. In EF, if your domain objects are modeled correctly, saving a parent object with modified children can be handled automatically within a single transaction. With a micro-ORM, you’re usually left orchestrating those inserts, updates, and deletes manually. The same is true with concurrency. EF has built-in mechanisms for detecting and handling conflicting updates. With a micro-ORM, that logic isn’t there unless you write it yourself. Individually, these problems may look like small coding tasks, but across a real-world project, they add up quickly. The perception that EF is inherently harder often comes from using it in a stripped-down way. If your EF entities are just table mirrors, then yes—constructing queries feels unnatural, and LINQ looks verbose compared to a raw SQL string. But the real issue isn’t the tool; it’s that EF is running in table-mapper mode instead of object-persistence mode. In other words, the complexity isn’t EF’s fault, it’s a byproduct of how it’s being applied. Neglect the domain model and EF feels clunky. Shape entities around business behaviors, and suddenly its features stop looking like bloat and start looking like time savers. Here’s a practical rule of thumb from real-world projects: Consider a micro-ORM when you have narrow, read-heavy endpoints and you want fine-grained control of SQL. Otherwise, the maintenance costs of hand-rolled mapping and relationship management usually surface down the line. Used deliberately, micro-ORMs serve those specialized needs well. Used as a default in complex domains, they almost guarantee you’ll spend effort replicating what EF already solved. Think of it this way: choosing a micro-ORM over EF isn’t wrong, it’s just a choice optimized for specific scenarios. But expect trade-offs. It’s like having only a toaster in the kitchen—perfect when all you ever need is toast, but quickly limiting when someone asks for more. The key point is that micro-ORMs and EF serve different purposes. Micro-ORMs focus on direct query execution. EF, when used properly, anchors itself around object persistence and domain logic. Treating them as interchangeable options leads to frustration because each was built with a different philosophy in mind. And that brings us back to the bigger issue. When developers say they’re fed up with EF, what they often dislike is the way it’s being misused. They see noise and friction, but that noise is created by reducing EF to a table-copying tool. The question is—what does that misuse actually look like in code? Let’s walk through a very common pattern that illustrates exactly how EF gets turned into a DTO factory, and why that creates so many problems later.

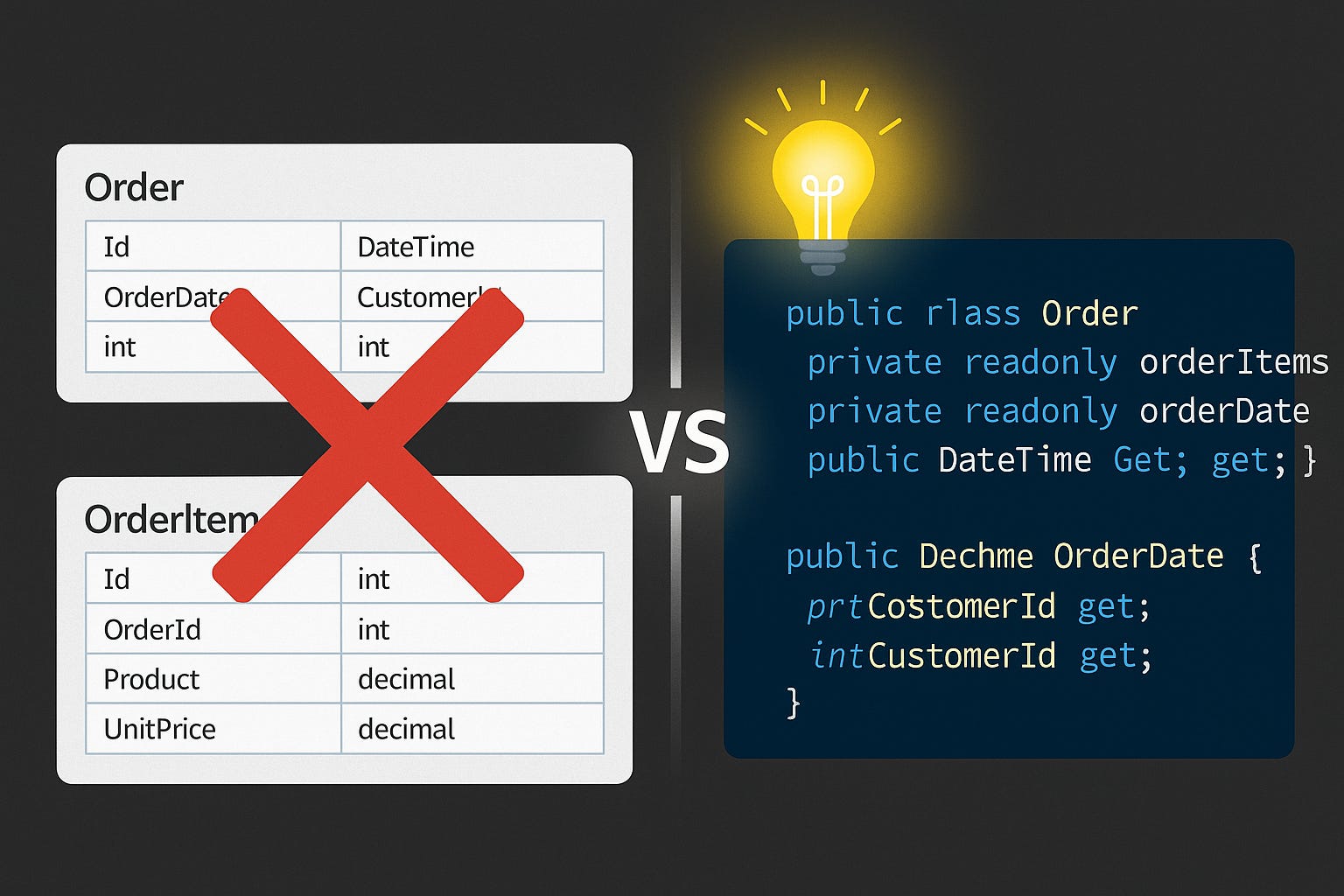

When EF Becomes a DTO Factory

When EF gets reduced to acting like a DTO factory, the problems start to show quickly. Imagine a simple setup with tables for Customers, Orders, and Products. The team scaffolds those into EF entities, names them `Customer`, `Order`, and `Product`, and immediately begins using those classes as if they represent the business. At first, it feels neat and tidy—you query an order, you get an `Order` object. But after a few weeks, those classes are nothing more than property bags. The real rules—like shipping calculations, discounts, or product availability—end up scattered elsewhere in services and controllers. The entity objects remain hollow shells. At this point, it helps to recognize some common symptoms of this “DTO factory” pattern. Keep an ear out for these red flags: your entities only contain primitive properties and no actual methods; your business rules get pulled into services or controllers instead of being expressed in the model; the same logic gets re‑implemented in different places across the codebase; and debugging requires hopping across multiple files to trace how a single feature really works. If any of these signs match your project, pause and note one concrete example—we’ll refer back to it in the demo later. The impact of these patterns is pretty clear when you look at how teams end up working. Business logic that should belong to the entity ends up fragmented. Shipping rules, discount checks, and availability rules might each live in a different service or helper. These fragmented rules look manageable when the project is small, but as the system grows, nobody has a single place to look when they try to understand how it works. The `Customer` and `Order` classes tell you