The Dancer (Ang Mánanayaw)

Description

The Dancer

by Rosauro Almario

Translated from the Tagalog (1910 Edition) by Gio Marron with AI assistance from ChatGPT, Claude, and Perplexity

Narration by Eleven Labs

Foreword

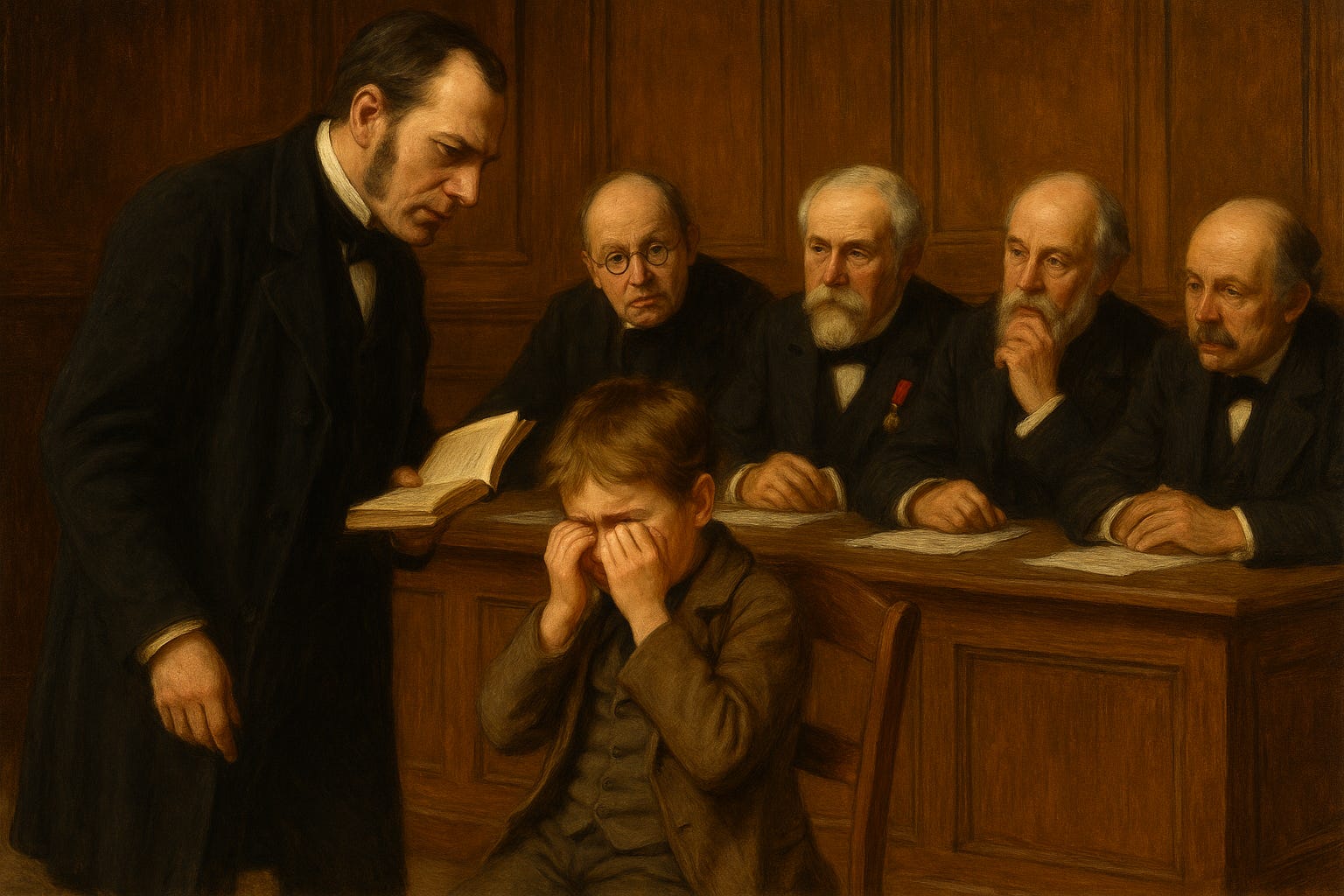

The Dancer (Ang Mánanayaw) by Rosauro Almario, first published in 1910 by Aklatang Bayan in Manila, is a short Tagalog novel that serves as both a literary work and a moral allegory. Written during the early American colonial period in the Philippines, it stands as a window into a society undergoing cultural, political, and moral upheaval. This translation seeks to preserve not just the story, but the rhetorical force, social commentary, and emotional tone of the original.

The novel follows Sawî, a provincial youth newly arrived in the city, and his fateful entanglement with Pati, a beautiful but cunning dancer in Manila. Their story is more than a tale of seduction and downfall; it is an exploration of urban corruption, class vulnerability, and the slow erosion of character under the pressure of illusion, lust, and modernity.

Almario writes with didactic urgency. The prose is steeped in the influence of Spanish literary traditions, evident in its rhetorical flourishes and formal tone, but it also draws from native Tagalog moral storytelling. This dual heritage reflects the transitional identity of early 20th-century Filipino literature, which sought to both entertain and instruct in a time of national redefinition.

The Dancer is not subtle. It is polemical, almost theatrical in its structure and tone, designed to shock, warn, and moralize. But in its theatricality lies its power. The dance halls of Manila become battlegrounds of virtue and vice. Pati, though framed as a femme fatale, is in fact a product of social decay—a survivor using what tools she has in a world that offers her few options. Sawî, for his part, is not simply a victim of seduction but of his own romantic delusions and failure to discern appearances from substance.

This translation uses modern English dialogue conventions and idioms while preserving the formal diction and tonal gravity of the original. Where the Tagalog text relies on repetition or florid metaphor, the English renders those ideas with clarity but does not omit them. The goal is not modernization but accessibility—to bring Almario's moral vision and artistic voice to readers unfamiliar with early Tagalog prose.

In its time, Ang Mánanayaw was part of a larger project by Aklatang Bayan: to use literature as a weapon in the fight against moral decline, colonial disorientation, and cultural amnesia. Today, it stands as a potent reminder of the tensions that defined Filipino identity in the shadow of empire, and the enduring battle between desire and dignity.

Gio Marron

The Dancer

Jóvenes qué estais bailando, al infierno vais saltando.[^1]

Chapter One: Beginning

Pati: A dancer. Of indeterminate stature; neither short nor tall; her body robust, full of vitality, radiantly fresh; her large bluish eyes like twin windows from which a burning soul gazed out, a soul ablaze with the flames of passion flowing with momentary pleasures—pleasures that could drown, irritate, and ultimately destroy any soul foolish enough to immerse itself in them.

Sawî[^2]: Born in the provinces, a young man pursuing his studies in Manila. Coming from a good family of means, Sawî was raised amidst plenty and comfort: timid, exceedingly shy, with somewhat delicate mannerisms, entirely unlike those city youths whose sole aspiration was to flit about like butterflies or bees, forever seeking new flowers from which to draw fragrance.

Tamád[^3]: A wastrel, a good-for-nothing, as the common folk called him. Orphaned of both father and mother. Without wife, child, sibling, or any relation except for one: "Joy"—a joy that, for him, could never be found in any place or corner save for billiard halls, cockpits, gambling dens, dance houses, and those ever-hungry jaws of hell that always stood ready to receive him.

"Tamád, how's the bird?" Pati inquired.

"Good news, Pati—he's becoming quite tame now," Tamád replied.

"Ready to enter the cage, then?"

"Oh, without a doubt he'll enter it willingly!"

"What has he said to you about me?" she probed further.

Tamád flashed a mischievous smile. "The same as when I first introduced you at that party. He declares you're beautiful as Venus herself, radiant as the Morning Star. He's already fallen for you! You can be certain he's ensnared in your net."

Pati parted her crimson lips to release a resonant laugh.

"So he's in love with me already, is he?"

"And he'll be searching for you later tonight."

"Where? Where did you tell him I would be?"

"At the dance hall."

"Then he already knows I'm a dancer?" she asked with feigned concern. "And what was his reaction? Hasn't he read those newspaper reports claiming that women who dance at subscription parties aren't women at all but merely a bundle of leeches in skirts?"

"He... he mentioned something of that nature," Tamád acknowledged. "But I assured him such rumors might occasionally hold truth, but not invariably. 'Pati,' I told him, 'that young woman I introduced at the party is living proof that a beautiful pearl may yet be found amidst the mud...'"

Tamád paused momentarily to swallow before continuing:

"And Sawî—our bird in question—believed me entirely. He's convinced you're a 'rare pearl,' a modest young woman of virtue and dignity."

"And didn't he question why I found myself in a dance hall?" Pati asked.

"He did ask—how could he not?" replied Tamád. "But the tongue of Tamád—your faithful procurer—created such elaborate dreams in that moment, painting images so lifelike they appeared as truth itself, witnessed by my own eyes. I told him, my voice nearly breaking with emotion: 'Oh, Sawî, if you only knew the complete history of Pati—the beautiful Pati whom you so admire—you would surely see her in your mind's eye as nothing less than a virtuous woman, a paragon of maidenhood. For she,' I continued dramatically, 'is an orphan who has endured considerable misfortune in life, reduced to begging, to pleading for alms, and when those she approached no longer extended their compassion, she was forced into servitude, selling her strength to a wealthy man... but...'"

"What happened next in this fabrication of yours?" Pati asked with an arched eyebrow.

"The wealthy man," Tamád continued with theatrical flair, "confronted with your unrivaled beauty, developed designs to violate your honor."

"Violate!" Pati scoffed. "You've quite a talent for weaving falsehoods. And what heroic action did I supposedly take?"

"You resisted his base desires with unwavering virtue."

"And then?"

"You departed from the house where you served to enter—by necessity—the profession of dancing."

"So in summary," Pati concluded with sardonic precision, "in Sawî's imagination, I am a virtuous woman, an orphan mistreated by Fate, who became a beggar, then a supplicant, a servant, essentially a slave; and because I defended my honor, I left the wealthy man's house to enter a different profession. Is that the fiction you've constructed?"

"Precisely so," Tamád affirmed with satisfaction.

Oh, if only God had ordained that lies, before leaving the lips of liars, should first transform into flames...!

Pati, to those of us who truly knew her, was nothing but a baitfish[^4]—outwardly displaying only the glittering shimmer of scales while harboring nothing but fetid mud within. She was not merely flirtatious or fickle; she was something far more dangerous—a predator, an executioner of souls unfortunate enough to fall into her embrace.

Even as a young girl—barely blossoming into womanhood—Pati had already inspired fear among the young men in her neighborhood. How could they not be wary when she would consent to anyone's advances, make promises to everyone, swear oaths to all comers? Each promise and oath was sealed with some token or pledge extracted from her victims—deposits that could never be reclaimed once given.

But now Tamád was speaking again. Let us listen to his words:

"Pati," he said with a smirk, "later tonight I shall certainly bring your bird to you."

"When you arrive," she replied coolly, "the cage will be ready and waiting."

And with that exchange, they parted ways.

Chapter Two: The Cage Opens

They had already arrived at the first step of the stairway that led into Pluto's realm[^5]: the dance hall. Tamád led the way, the tempter, while Sawî followed timidly behind him.

The Temple of the cheerful goddess Terpsichore[^6], at that moment, transformed into a veritable Garden of Delights: everywhere the eye turned, it beheld nothing but modern-day Eves and latter-day Adams. Throughout this Eden, flowers seemed to have scattered themselves of their own accord, while human butterflies flitted to and fro, dancing around one another in perpetual motion.

Upon the arrival of Sawî and Tamád at the dance hall, Pati, who had been waiting for them, cheerfully came forward and, with a smile and a laugh, greeted them:

"You've wandered in here..."

Sawî did not respond. Pati's words, those utterances that seemed as if dipped in sweetness, reached one by one into the heart of the stunned young man. How beautiful Pati looked at that moment!

Inside her dress that shimmered with light, in Sawî's vision she resembled what Flammarion saw in his dream: a person made of light, and her hands were two wings.

Tamád, seeing his companion freeze like this, winked once at Pati and secretly pointed to him: "He's truly awkward!"

Just then, a s