The Two Churches Of ’Quawket.

Description

The Elephant Island Chronicles

Presents

The Two Churches Of ’Quawket.

From “SHORT SIXES”

Stories To Be Read While The Candle Burns

By H. C. Bunner

Illustrated by F. Opper

Narration by Eleven Labs

Foreword

In the charming tradition of American regional storytelling, The Two Churches of 'Quawket by H.C. Bunner offers a delightful lens into the peculiarities of small-town life, a world where the mundane is rendered extraordinary through the keen eyes of a satirist. Originally penned during the late 19th century, the tale embodies Bunner’s remarkable ability to distill humor and humanity from the rivalries and rituals of everyday people.

The story is a testament to Bunner’s mastery of the short form, a genre he elevated with his sharp wit and warm irony. It introduces readers to 'Quawket, a fictional New England village divided not by geography but by faith, with its Episcopal and Congregationalist churches standing as symbols of friendly—and sometimes not so friendly—competition. Through his vivid characters and sparkling prose, Bunner explores the nuances of community dynamics, shining a light on the universal themes of pride, reconciliation, and the search for common ground.

What sets Bunner apart is his profound empathy for his characters. He gently pokes fun at their foibles but never derides them, crafting a narrative that is as heartwarming as it is humorous. This delicate balance makes The Two Churches of 'Quawket not merely a story of its time but a timeless exploration of human nature.

Whether you’re a lover of classic literature, an admirer of satire, or simply a curious reader seeking an escape into a world both familiar and quaintly foreign, this story promises to enchant, entertain, and perhaps even provoke a knowing smile. Let us step into the village of 'Quawket, where the ringing of church bells and the occasional clash of wills create a symphony of life worth savoring.

Gio Marron

The Two Churches Of ’Quawket.

From “SHORT SIXES”Stories To Be Read While The Candle BurnsBy H. C. BunnerIllustrated by F. Opper

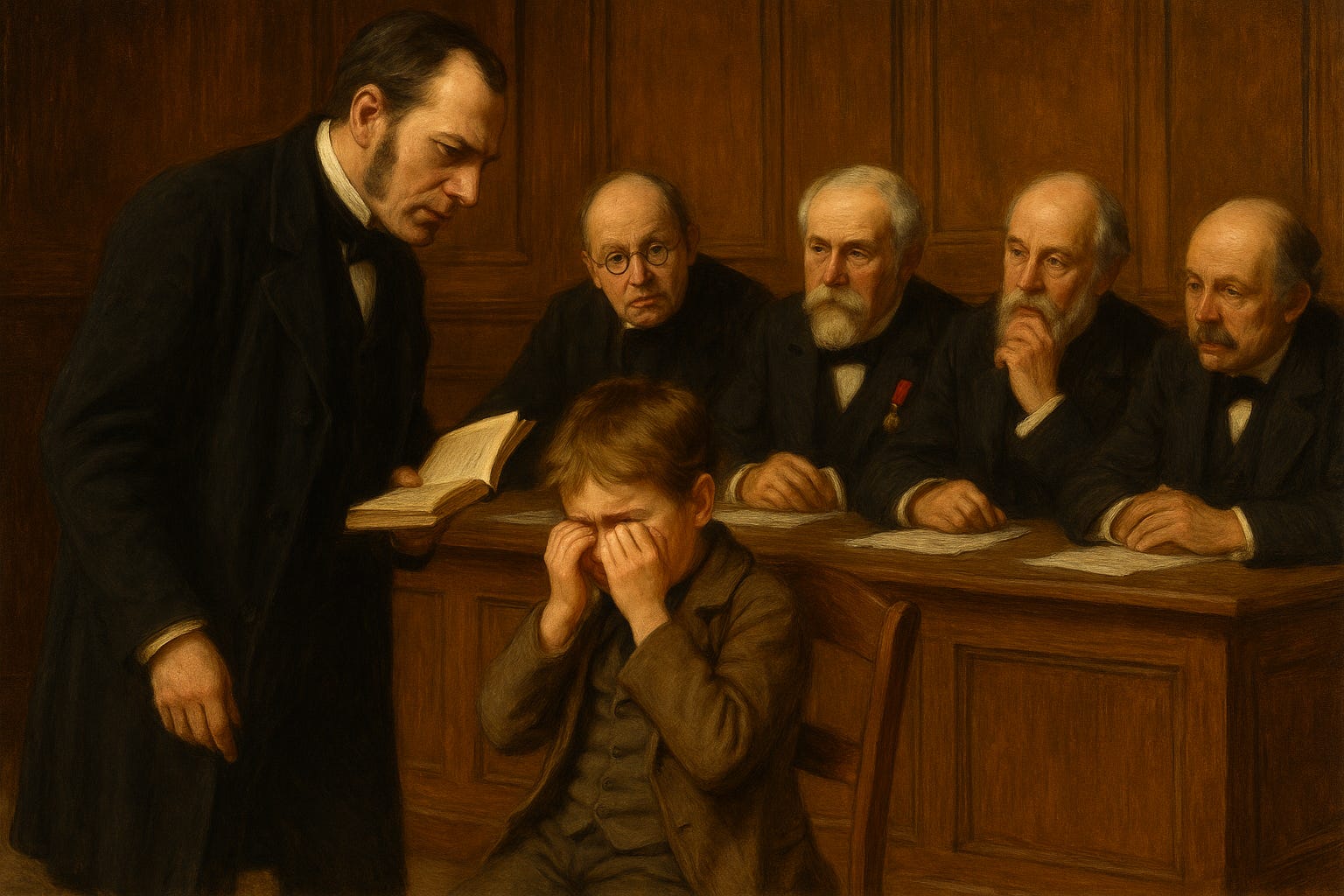

“’Read it!’ commanded Brother Joash. The minister grew pale.”

The Reverend Colton M. Pursly, of Aquawket, (commonly pronounced ’Quawket,) looked out of his study window over a remarkably pretty New England prospect, stroked his thin, grayish side-whiskers, and sighed deeply. He was a pale, sober, ill-dressed Congregationalist minister of forty-two or three. He had eyes of willow-pattern blue, a large nose, and a large mouth, with a smile of forced amiability in the corners. He was amiable, perfectly amiable and innocuous—but that smile sometimes made people with a strong sense of humor want to kill him. The smile lingered even while he sighed.

Mr. Pursly’s house was set upon a hill, although it was a modest abode. From his window he looked down one of those splendid streets that are the pride and glory of old towns in New England—a street fifty yards wide, arched with grand Gothic elms, bordered with houses of pale yellow and white, some in the homelike, simple yet dignified colonial style, some with great Doric porticos at the street end. And above the billowy green of the tree-tops rose two shapely spires, one to the right, of granite, one to the left, of sand-stone. It was the sight of these two spires that made the Reverend Mr. Pursly sigh.

With a population of four thousand five hundred, ’Quawket had an Episcopal Church, a Roman Catholic Church, a Presbyterian Church, a Methodist Church, a Universalist Church, (very small,) a Baptist Church, a Hall for the “Seventh-Day Baptists,” (used for secular purposes every day but Saturday,) a Bethel, and—“The Two Churches”—as every one called the First and Second Congregational Churches. Fifteen years before, there had been but one Congregational Church, where a prosperous and contented congregation worshiped in a plain little old-fashioned red brick church on a side-street. Then, out of this very prosperity, came the idea of building a fine new free-stone church on Main Street. And, when the new church was half-built, the congregation split on the question of putting a “rain-box” in the new organ. It is quite unnecessary to detail how this quarrel over a handful of peas grew into a church war, with ramifications and interlacements and entanglements and side-issues and under-currents and embroilments of all sorts and conditions. In three years there was a First Congregational Church, in free-stone, solid, substantial, plain, and a Second Congregational Church in granite, something gingerbready, but showy and modish—for there are fashions in architecture as there are in millinery, and we cut our houses this way this year and that way the next. And these two churches had half a congregation apiece, and a full-sized debt, and they lived together in a spirit of Christian unity, on Capulet and Montague terms. The people of the First Church called the people of the Second Church the “Sadduceeceders,” because there was no future for them, and the people of the Second Church called the people of the First Church the “Pharisee-mes”. And this went on year after year, through the Winters when the foxes hugged their holes in the ground within the woods about ’Quawket, through the Summers when the birds of the air twittered in their nests in the great elms of Main Street.

If the First Church had a revival, the Second Church had a fair. If the pastor of the First Church exchanged with a distinguished preacher from Philadelphia, the organist of the Second Church got a celebrated tenor from Boston and had a service of song. This system after a time created a class in both churches known as “the floats,” in contradistinction to the “pillars.” The floats went from one church to the other according to the attractions offered. There were, in the end, more floats than pillars.

The Reverend Mr. Pursly inherited this contest from his predecessor. He had carried it on for three years. Finally, being a man of logical and precise mental processes, he called the head men of his congregation together, and told them what in worldly language might be set down thus:

There was room for one Congregational Church in ’Quawket, and for one only. The flock must be reunited in the parent fold. To do this a master stroke was necessary. They must build a Parish House. All of which was true beyond question—and yet—the church had a debt of $20,000 and a Parish House would cost $15,000.

And now the Reverend Mr. Pursly was sitting at his study window, wondering why all the rich men would join the Episcopal Church. He cast down his eyes, and saw a rich man coming up his path who could readily have given $15,000 for a Parish House, and who might safely be expected to give $1.50, if he were rightly approached. A shade of bitterness crept over Mr. Pursly’s professional smile. Then a look of puzzled wonder took possession of his face. Brother Joash Hitt was regular in his attendance at church and at prayer-meeting; but he kept office-hours in his religion, as in everything else, and never before had he called upon his pastor.

Two minutes later, the minister was nervously shaking hands with Brother Joash Hitt.

“I’m very glad to see you, Mr. Hitt,” he stammered, “very glad—I’m—I’m—“

“S’prised?” suggested Mr. Hitt, grimly.

“Won’t you sit down?” asked Mr. Pursly.

Mr. Hitt sat down in the darkest corner of the room, and glared at his embarrassed host. He was a huge old man, bent, heavily-built, with grizzled dark hair, black eyes, skin tanned to a mahogany brown, a heavy square under-jaw, and big leathery dew-laps on each side of it that looked as hard as the jaw itself. Brother Joash had been all things in his long life—sea-captain, commission merchant, speculator, slave-dealer even, people said—and all things to his profit. Of late years he had turned over his capital in money-lending, and people said that his great claw-like fingers had grown crooked with holding the tails of his mortgages.

A silence ensued. The pastor looked up and saw that Brother Joash had no intention of breaking it.

“Can I do any thing for you, Mr. Hitt?” inquired Mr. Pursly.

“Ya-as,” said the old man. “Ye kin. I b’leeve you gin’lly git sump’n’ over ’n’ above your sellery when you preach a fun’l sermon?”

“Well, Mr. Hitt, it—yes—it is customary.”

“How much?”

“The usual honorarium is—h’m—ten dollars.”

“The—whut?”

“The—the fee.”

“Will you write me one for ten dollars?”

“Why—why—” said the minister, nervously; “I didn’t know that any one had—had died—“

“There hain’t no one died, ez I know. It’s my fun’l sermon I want.”

“But, my dear Mr. Hitt, I trust you are not—that you won’t—that—“

“Life’s a rope of sand, parson—you’d ought to know that—nor we don’t none of us know when it’s goin’ to fetch loost. I’m most ninety now, ’n’ I don’t cal’late to git no younger.”

“Well,” said Mr. Pursly, faintly smiling; “when the time does come—“

“No, sir!” interrupted Mr. Hitt, with emphasis; “when the time doos come, I won’t have no use for it. Th’ ain’t no sense in the way most folks is berrid. Whut’s th’ use of puttin’ a man into a mahog’ny coffin, with a silver plate big’s a dishpan, an’ preachin’ a fun’l sermon over him, an’ costin’ his estate good money, when he’s only a poor deef, dumb, blind fool corpse, an’ don’t get no good of it? Naow, I’ve be’n to the undertaker’s, an’ hed my coffin made under my own sooperveesion—good wood, straight grain, no knots—nuthin’ fancy, but doorable. I’ve hed my tombstun cut, an’ chose my text to put onto it—’we brung nuthin’ into the world, an’ it is certain we can take nu