Active Directory: The Crown Jewel Hackers Hunt

Description

What’s the one system in your environment that, if compromised, would let an attacker own everything—logins, files, even emails? Yep, it’s Active Directory. Before we roll initiative, hit Subscribe so these best-practices get to your team.

The question is: how exposed is yours? Forget firewalls for a second. If AD is a weak link, your whole defense is just patchwork. By the end, you’ll have three concrete areas to fix: admin blast radius, PKI and templates, and hybrid sync hygiene.

That means you’ll know how to diagnose identity flaws, remediate them, and stop attackers before they loot the vault. And to see why AD is every hacker’s dream prize, let’s start with what it really represents in your infrastructure.

Why Attackers Treat AD Like the Treasure Chest

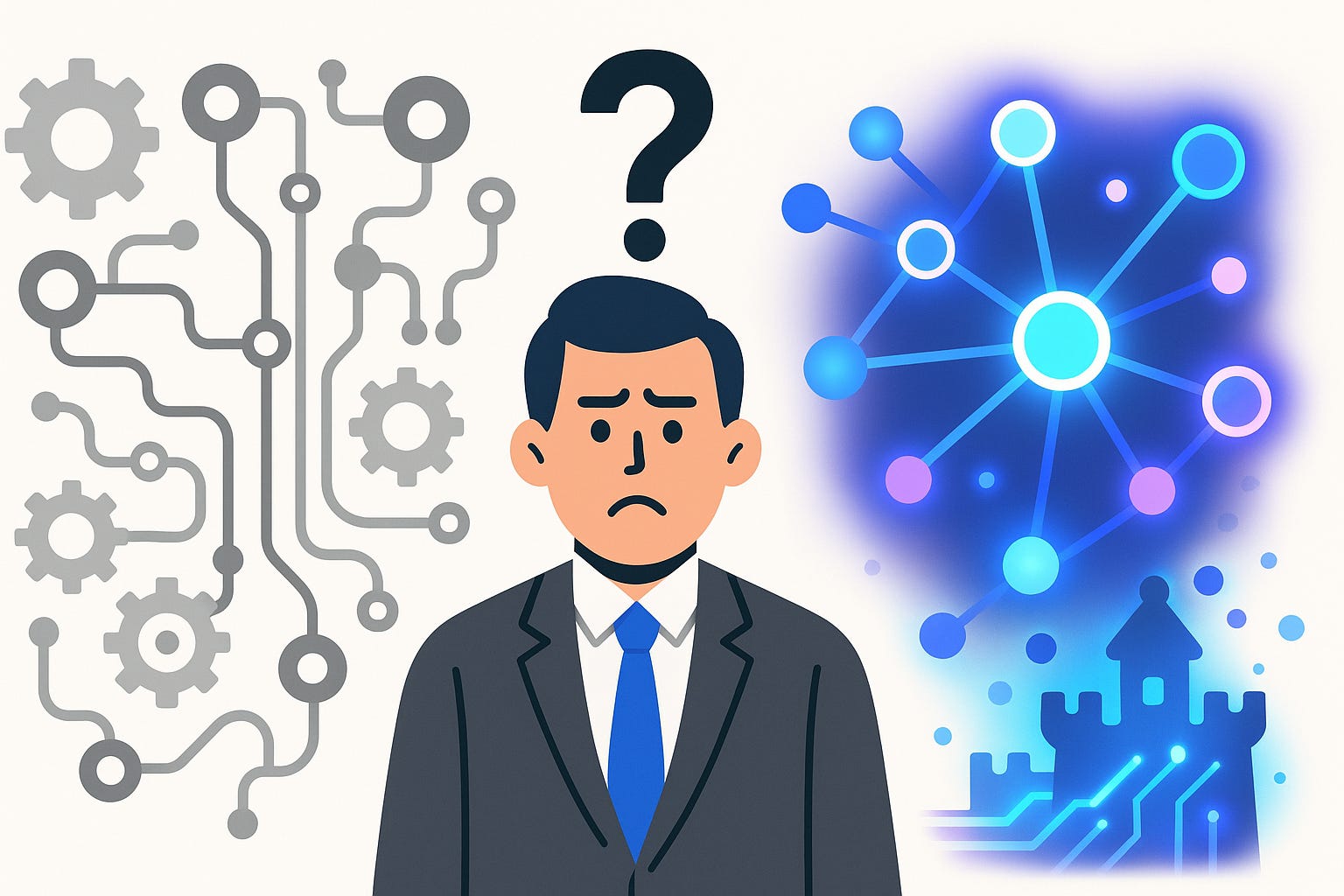

Picture one key ring that opens every lock in the building. Doesn’t matter if it’s the corner office, the server rack, or the vending machine—it grants access across the board. That’s how attackers see Active Directory. It’s not just a directory of users; it’s the single framework that determines who gets in and what they can touch. If someone hijacks AD, they don’t sneak into your network; they become the one writing the rules.

AD is the backbone for most day-to-day operations. Every logon, every shared drive, every mailbox lives and dies by its say‑so. That centralization was meant to simplify management—one spot to steer thousands of accounts and systems. But the same design creates a single point of failure. Compromise the top tier of AD and suddenly the attacker’s decisions ripple across the environment. File permissions, security policies, authentication flows—it’s all under their thumb.

The trust model behind AD did not anticipate the kind of threats we face today. Built in an era where the focus was on keeping the “outside” dangerous and assuming the “inside” could be trusted, it leaned heavily on implicit trust between internal systems. Machines and accounts exchange tokens and tickets freely, like everyone is already vetted. That architecture made sense at the time, but in modern environments it hands adversaries an advantage. Attackers love abusing that trust because once they get a foothold, identity manipulation moves astonishingly fast.

This is why privilege escalation inside AD is the ultimate prize. A foothold account might start small, but with the right moves an attacker can climb until they hold domain admin rights. And at that point, they gain sweeping control—policies, credential stores, even the ability to clean up their own tracks. It doesn’t drag out over months. In practice, compromise often accelerates quickly, with attackers pivoting from one box to domain‑wide dominance using identity attacks that every penetration tester knows: pass‑the‑hash, golden tickets, even DCSync tricks that impersonate domain controllers themselves.

Think of it like the final raid chest in an RPG dungeon. The patrols, traps, and mid‑tier loot are just steps in the way. The real objective is the treasure sitting behind the boss. Active Directory plays that role in enterprise infrastructure. It indirectly holds the keys to every valuable service: file shares, collaboration platforms, email—you name it. That’s why when breaches escalate, they escalate fast. The attacker isn’t chasing scraps of data; they’re taking over the entire castle vault.

And the stories prove it. Time and again, the turning point in an incident comes when AD is breached. What might start with one compromised workstation snowballs. Suddenly ransomware doesn’t just freeze a single device—it locks every machine. Backups are sabotaged, group policies are twisted against the company, and entire businesses halt in their tracks. All the well‑tuned firewalls and endpoint protections can’t help if the directory authority itself belongs to the intruder.

Yet many admins treat AD as a background utility. They polish the edge—VPN gateways, endpoint agents, intrusion detection—but leave AD on defaults, barely hardened. That’s like building five walls around your kingdom yet leaving the treasury door propped open. Attackers don’t have to storm the ramparts. They slide in through overlooked accounts, neglected service principals, or misconfigured trusts, and once inside, AD gives them the rest of the keys automatically.

The sad reality is attackers rarely need exotic zero‑days. AD crumbles for reasons far more boring: old accounts still holding broad rights, privileges never separated properly, or stale configurations no one wanted to touch. Those gaps are so common that seasoned pen testers expect to find them. And they’re spectacularly effective. With default structures still in place, attackers pass tickets, harvest cached credentials, and elevate themselves without tripping alerts. Security dashboards may look calm while the kingdom is already being looted.

So while administrators often imagine the weak point must be a rare protocol quirk or arcane privilege trick, the truth is far less glamorous. The cracks most often sit in sight: over‑privileged service accounts, tiering violations, unmonitored trusts. It only takes one such oversight to give adversaries what they want. And from there, you’re no longer facing “a” hacker inside your system—they are the system’s authority.

But here’s where it gets sharper. Attackers don’t need to compromise dozens of accounts. They only need one opening, one user identity they can wedge open to start climbing. And as you’ll see, that single chink in the armor can flip the whole game board before you even know it happened.

The First Crack: One User to Rule Them All

The first weak spot almost always begins with a single user account. Not an admin, not a vault of secrets—just an everyday username and password. That’s all it takes for an attacker to start walking the halls of your network as if they own the badge.

Look at the common ways that badge gets picked up. A phishing email reaches the wrong inbox. A reused password from someone’s old streaming account still unlocks their work login. Or a credential from a third‑party breach never got changed back at HQ. In each case, the attacker doesn’t need to smash through defenses—they just log in like it’s business as usual.

Here’s the part many IT managers get wrong. They assume one user account compromise is a nuisance, not a disaster. At worst, an inbox, maybe a department share. The truth is different. In Active Directory, that account isn’t a pawn you can ignore—it’s a piece that can change the entire board state.

And the change happens through lateral movement. Attackers don’t linger in one mailbox. They pull cached credentials, replay tokens, and hunt for admin traces on machines. Attackers look for cached credentials or extract LSASS memory and replay hashes—standard playbook moves listed in the course material. Pass‑the‑hash means they don’t even need the password itself. They recycle the data stored in memory until it opens a bigger door. Tools like Mimikatz make this as straightforward as copy and paste.

What makes it worse is how normal these moves look. Monitoring systems are primed for red flags like brute‑forcing or failed logins. But lateral movement is just a series of valid connections. To your SIEM, it looks like a helpdesk tech doing their job. To the attacker, it’s a stealth climb toward the crown.

That quiet climb is why this stage is dangerous. Each login blends in with the daily noise, but with every hop, the attacker closes in on high‑value accounts. Tools like BloodHound even map the exact attack paths, showing how one user leads cleanly to domain admin. If the adversaries run those graphs, you can guarantee defenders should too.

From that initial account, the escalation accelerates. One compromised workstation leads to cached credentials for someone else. Soon, an admin token shows up on a box where it shouldn’t. That token unlocks servers, and with servers come backups, databases, and policy control. In a handful of hours, “that hacked HR login” becomes “domain admin on every system.”

Notice this isn’t elite wizardry. It’s standard practice. The playbooks are published, the tools are free, and modern attack kits automate discovery and replay. This lowers the bar for attackers—what once took skill now takes persistence and a weekend of googling. Automation means compromise moves quickly, and defense has to move faster.

The other problem comes when defenders create shortcuts without realizing it. Same local admin password across machines? The attacker cracks one, spreads everywhere. Privileged accounts logging into workstations? Those tokens sit waiting on boxes you don’t expect. AD doesn’t second‑guess these logins; it trusts them. That trust becomes the attacker’s ladder upward.

And by the time someone notices, the scope has already multiplied. It’s no longer “one compromised account.” It’s dozens of accounts, across multiple systems, chained together into a network‑wide takeover.

This is why treating a single stolen credential as low‑impact is a critical mistake. In an Active Directory context, that one login can become the master key. What looks like an everyday helpdesk ticket—“I clicked a link and now I can’t log in”—might already be the start of a saboteur rewriting the rules behind the curtain.

Which raises the next question: what cracks inside AD make it this easy to escalate? Because often it isn’t the attacker’s brilliance that decides the outcome—it’s the misconfigurations left glowing like beacons. And as we’ll see, those mistakes can make your environment look like it’s advertising “Hack me” in neon.

Critical Misconfigurations That Scream ‘Hack Me’

The cracks that matter most in AD often aren’t flashy exploits but boring missteps in configuration. And those missteps cr