The Podcast - Episode 5: Danielle Christmas on Being Intentional about Race and the Regency

Description

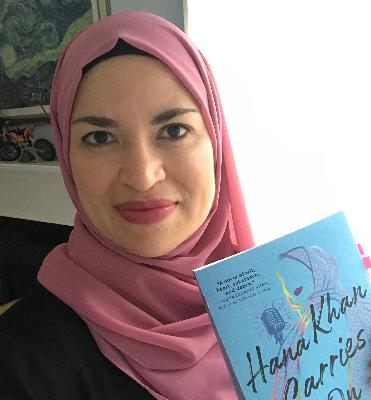

Professor Danielle Christmas is a scholar in English and Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In her day-job, she researches serious topics about race and history, from white nationalism to the legacy of slavery and the Holocaust, and how issues like this are depicted in our cultural currency.

But when she’s off the clock and needs to unplug, Danielle Christmas turns to Jane Austen. And she says even though she doesn't always want to, she can't help bringing her knowledge of race and history into these stories.

As co-editor of the most recent issue of the JASNA journal Persuasions Online, Danielle Christmas has become a convener of conversations within the Janeite and academic community on race and the works of Jane Austen. She took some time recently to chat with us about that issue, and everything from Fanny Price and the history behind Mansfield Park, to binging “Bridgerton.” And she says, for her, escaping to a Regency world can be both guilt-free and fruitful. Here's our conversation.

Danielle Christmas

Sometimes I really like the idea of putting my brain to the use of just having fun - of playing around in a text that's beautifully written and is doing subtle work, right? [During the day] I'm talking about slavery and the Holocaust. And my new work is on white nationalism. That's loud, there’s nothing [subtle] about that. And you have to pay attention to the corners and the contours of what's happening in [Jane Austen’s] novels, in order to really understand the stakes. And it's just a good brain exercise [and] it trains me to pay attention to the small things. Whereas maybe if I'm spending all of my time, just looking at the loud - you know, the loudness, the violence, all of that - I miss the corners.

Plain Jane

Well tell me, Danielle, because you are reading with all of that loudness around you. And you're very aware of this and you're … choosing to dedicate the time to exploring all those issues in our culture, everything from our lynching histories in our culture and the legacy of slavery and the legacy of racism. What do you bring as a reader with your expertise to Jane Austen, does that enter into it very much? Do you find comfort in the fact that she was surrounded by these conversations? And they are, like you say subtle, but they might be there like Edward Said says, - look at what's not there as well as what is there.

Danielle Christmas

Yes, exactly! That it's always there. Even if it's not there. It's there and it's absence and the fact that it's absent, is itself indicating something that we should be thinking about that's doing something whether or not it's present in the room.

I think it's fascinating that people that we talk to so much in this special issue that we're doing [in] Persuasions, there is a lot going on, of course about the triangle trade and how that works. And yet there are four lines in Mansfield Park … or the sum total of what Jane Austen clearly said, explicitly said - explicitly-ish! - that is her making a direct reference to slavery.

If we, we smart people, we smarty-pants people, have so much to say, based on four lines and its absence, then there really is something fascinating going on. Anytime there is a narrative, a television series, a book, anything that has to do, it is deeply embedded in a construction of class culture, right? And manners. There are all sorts of politics that surround that. And she was right. …

She was a brilliant woman and a brilliant writer who wrote knowing that, right? It's intentional. I think that sometimes it's fascinating to encounter resistance among people who love Jane Austen, out of fear, I think, that we're pushing politics into a space where it's like a protected space. So why are we bringing politics into yet another thing, right? Like, why are we? It's there! … If we were living in Regency times, there's no way to read her work without understanding it as construction of political narrative.

Not only that, or maybe not primarily that, but to write a romance novel at the time is itself a political exercise. And so acknowledging the truth of that - two things can be true at the same time. This is what I like, my major discovery in my 30s: Things can be true, a person can be, you know, racist and fascinating; a person could be writing just enjoyable romantic fiction, and also be doing something interesting and political. And I think that's what's happening. And it's easy to to get our hackles up on either side of that, to insist that it is only politics. And to forget that it's more fascinating.

So why are we bringing politics into yet another thing, right? Like, why are we? It's there! … If we were living in Regency times, there's no way to read her work without understanding it as construction of political narrative.

I think maybe this is my pop culture brain. But it's more fascinating because it's not just politics, right? Like she's doing something that is supposed to be an exercise in entertainment and pleasure. But she's playing this all out. And in a tableau that's tends to be people of a certain like wealth and class and that money comes from someplace, their comfort comes from someplace, the exclusion or not, of people.

You cannot read Mansfield Park outside of those four lines, without understanding Fanny, and her absence of wealth, her relationship to the wealthier family, and the way that that interaction works as anything except a political inquiry into how relationships with family and money work and power, and morals and ethics, right?

Plain Jane

So everything you say, Danielle, so interesting about Mansfield Park: They have to get their money at Mansfield Park from somewhere. You mentioned the four lines about “dead silence.” There's so much in that novel, if you're closely reading the text, that are choices that Jane Austen is making. And … she's so good at her job that we forget that there's a puppeteer. There's a conductor, who's making choices about how Mansfield Park gets its money, about where Sir Thomas goes when he leaves Mansfield Park, about what Fanny Price is reading. So much more than the “dead silence,” you know?

So tell me more. Danielle, when I read it, it occurred to me that it's not it doesn't seem to me like too much of a stretch to see Mansfield Park and its dismantling, I would say it's kind of reduced to rubble. By the end of it. It's kind of destroyed! And the only person who's still standing is Fanny Price. And I feel like it could be a metaphor for a sort of dismantling of England through colonialism - morally - not paying attention to your house, being out there and not concentrating on what's real and what's actually ethical. And the consequences of that. Do you think that's too much of a stretch?

Danielle Christmas

That’s provocative! I kind of love that! I would have to sit and think about that.

I think if that's plausible, and as a sort of larger metaphor, I think that maybe … you'll get my preemptive defenses against those people who tend to in general, tell me I'm bringing politics into politics-free spaces. So [they’ll say], “It's just romance. Right? It's happy. It's just pop culture. Why are you insisting?”

I think because of that, I tend to be more conservative in the claims that I make than you're being.

I think that my the most conservative account that I could easily defend - that I think that any person could reasonably defend: After you learn a little bit about Jane Austen's family in general (I resist psychoanalytic readings of an author through their work, don't think it's helpful), but you can't find out that her father has a trustee relationship with a plantation, or find out that her brother would patrol waters for slave ships, and not think about how knowing that in her relationship to them, and doing that would inform her decision to write this novel. And what to include, and not.

So I think the most conservative thing to say about slavery, history, [and] politics, and the novel, is that just the insistence that she's publishing this, and that she's insisting that people who like her novels, and enjoy her kind of writing, read this.

That is disruption. That is interesting. Just that, yes. So, just even stopping there, makes me curious.

I think sometimes I feel like my job as a teacher, maybe less so in my writing, but as a teacher, is just to make us notice things that we noticed, but didn't realize were important to notice. Like to just say if I was teaching a class, like, what do you guys think that a woman who was writing what we could call - even at the time -chicklit, right? Like a woman who's writing - yes, a smart woman - who's writing for other literate smart women, inasmuch as any woman is considered especially smart and literate at the time, who's interested in reading a romantic novel happened to do this. Like happens to mediate this particular story through the experience of a deep privilege? And, what you're saying, which is really the kind of collapse of privilege in one family, right? So, like, and this is where we're going. Just think about that, guys.

I'm a new historicist. So I want to know what's going on all around the page. I want to know what helped make the story and I want to know what the story is doing off of the page.

And so there is an entire ecosystem around what we can talk about - this really weird thing she did, right? Like, it's just a weird thing! There's a way to have told that story, so that all I needed to do was curl up on my couch and read it and not really have to do any heavy lifting. Not grappl