Vivienne Ming on hybrid collective intelligence, building cyborgs, meta-uncertainty, and the unknown infinite (AC Ep13)

Description

“What I need is someone who will have an idea I would never have had. In fact, better yet, an idea no one else in the world would ever have. That’s human space. That’s our job now: the unknown infinite.”

–Vivienne Ming

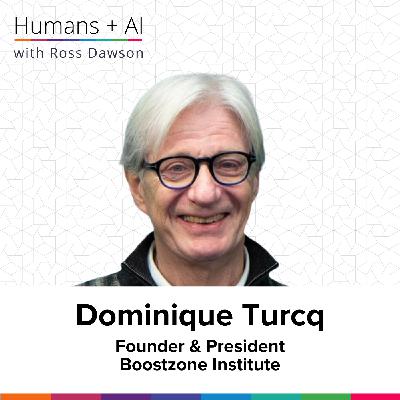

About Vivienne Ming

Vivienne Ming is a theoretical neuroscientist, entrepreneur, and author. Her AI inventions have launched a dozen companies and nonprofits with a focus on human potential, including Socos Labs and Dionysus Health. She is Professor at UCL Global Business School for Health, with her work featured in media including Financial Times, The Atlantic, and New York Times.

Website:

LinkedIn Profile:

X Profile:

What you will learn

Unlocking human potential through AI

Building health systems with humans and machines

Why AI should challenge—not replace—us

The danger of cognitive atrophy in education

Fostering metacognition and meta-uncertainty

Diversity as a driver of collective intelligence

Preparing for a future of infinite unknowns

Episode Resources

Transcript

Ross Dawson: Vivian, it is fantastic to have you on the show.

Vivienne Ming: It’s a pleasure to be here.

Ross: So you are being described as obsessed with using technology to maximize human potential. So that’s a big topic, where, how do you see it? What is the potential?

Vivienne: Yeah, I mean, when I was interviewing to go to grad school, I used to tell people that I wanted to build cyborgs, which is an excellent way to get everyone to scoot away from you for fear that your crazy will rub off and they won’t get accepted either.

But one of my claims to notoriety is when my son was diagnosed with type one diabetes, I hacked all those medical equipment. Turns out, I broke all sorts of US federal regulations. And little did I know at the time, I invented one of the first ever AIs for diabetes.

And I mention that here in answer to your lead-in because as much as I’m thrilled that I helped my son—it’s a project I’m more proud of than any other—there is some kid in a favela in Rio, a village outside Kinshasa, down the street from me here in California. This kid has the cure—not some crummy AI, not a treatment, a cure for diabetes—in their potential.

But the overwhelming likelihood is they’re never going to live the life that allows them to bring that into the world.

And there’s tons of research on this. I’m a hard number scientist, so words like human potential can feel very flowery. But to me, it’s grounded and sort of strangely selfish. What could all of these lives be doing transforming the world for the better?

And for some reason, we are so under-motivated to make that potential a reality. So this is—when I come at these sorts of problems, that’s really where I’m coming from.

And I’ll even share, just as a personal motivation, I spent a solid chunk of the 90s miserable and homeless. And since then, I’ve gotten to found—or been involved in founding—12 different companies. I’ve invented six life-saving inventions. I’ve written books. I’ve gotten to do so many things.

And I get it. I have a weird life, a wonderful life. Maybe not everyone’s going to have that same life, but everyone could.

And how many lives never got off the streets, or never got out of the favela? Or, for that matter, how many lives were, exceptional in some sense, but kind of stalled out at a solid job somewhere, doing something anyone else could have done?

But you enjoy things and you led a good life. But again, you could have done something transformative, and the world didn’t call on you. It didn’t give you that opportunity.

That’s what human potential is about for me.

Ross: Fantastic. And so I think just digging into that healthcare piece—so one of the really interesting things about diabetes, or AI and diabetes, is this idea of a closed system, where the human and the AI system—as it is data coming to human to be able to adjust glucose levels and so on…

And I think some of your other work around, for example, bipolar or other domains as well, where it’s looking at humans and AI as a system—where humans are, we are obviously an integral system—but we have data, and we’re using the AI or technology as an external system to be able to build a bigger system which can enhance our health, be that in glucose levels, be that in our ability to respond to ways our neurology is going awry.

<span style="