Why Do We Tax Businesses at All?

Description

We want real prosperity for working Americans without piling debt on future generations.

So, we’ve got to be open to new ideas. Some of those ideas might sound like they’ll never work. That’s fine. What matters is that we consider the options, build consensus, and stay focused on the results, not just the method.

Consensus makes lasting change possible. If we build real consensus across parties and regions, then we open the door to a rarity in American policy: a permanent solution. Not a temporary fix. Not a patch for the next election cycle. We need a system that works because enough people agree on the goal and not the method for achieving that goal.

Achieving the goal matters. How we get there is secondary.

There’s another angle we need to consider. When we’re looking at solutions, we have to be willing to think all the way to the edges. On one end of the spectrum is the “do nothing” option. This option is something we should consider even when everyone’s yelling that we have to act. On the other end is the option that delivers overwhelming, decisive results.

At both ends, we have to ask: Why wouldn’t that work? And if we can’t find a good answer, then maybe that so-called extreme isn’t extreme at all. Maybe it’s the best option we’ve got.

So, with that in mind, here’s a question worth asking:

If our goal is food on the table and heat in the house for all American workers, why do we tax businesses at all?

If that made you pause or even angry, that means we’re asking the right question.

Goals Matter More Than Methods

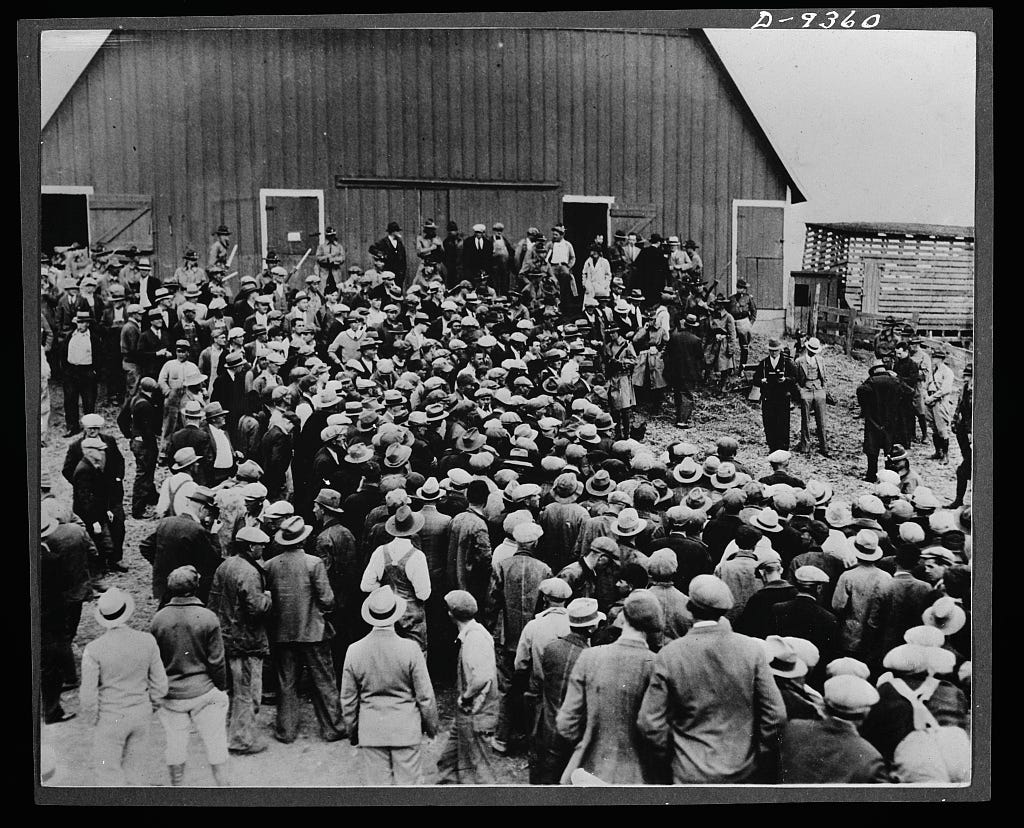

During World War II, America faced a nearly impossible problem. The country needed tanks, planes, and ships. We needed millions of them. We needed them fast. But at the time, the factories that could build them were busy making cars, stoves, and washing machines.

The problem was so dire that adversary global leaders assessed there was no way we could achieve our goals and win the war. Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, one of Adolf Hitler’s top lieutenants, said that Americans could only make refrigerators and razor blades. He assessed we would never be able to produce the military equipment and supplies necessary to defeat Nazi Germany.

At the time, Göring was right.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt knew it, too. So, Roosevelt started building consensus in order to create permanent effects to win the war.

And he had a tough row to hoe. Many thought FDR was anti-business. He had expanded government oversight of banking, labor, and markets. He raised income taxes on the wealthy and introduced new corporate taxes many saw as hostile to business investment. He supported unions and workers’ rights that businesses viewed as empowering strikes and weakening employer control. He framed the wealthy elite as obstacles to recovery.

But FDR wasn’t anti-business. He was pro-American worker. He opposed exploitation. He knew he needed a strong business culture. In his annual Budget Message to Congress on January 5, 1942, FDR said…

“We cannot outfight our enemies unless, at the same time, we outproduce our enemies. It is not enough to turn out just a few more planes, a few more tanks, a few more guns, a few more ships, than can be turned out by our enemies. We must outproduce them overwhelmingly, so that there can be no question of our ability to provide a crushing superiority of equipment in any theater of the world war.”

FDR’s administration couldn’t mandate patriotism or force companies to comply. It had to make the pivot profitable. The administration partnered with industry and offered massive contracts, tax incentives, and full-throttle support to retool factories for war production.

The government offered something called cost-plus contracts. For every dollar a company spent retooling its factory, it got that dollar back, plus a guaranteed profit. There were advance payments, tax incentives, and full reimbursement for production costs. That meant zero financial risk for the companies. If they stepped up, they didn’t just help the country. They came out ahead.

Ford built a mile-long assembly line just for B-24 bombers. Chrysler stopped making cars and started producing tanks. General Motors converted its plants to churn out machine guns and aircraft engines. These weren’t small measures. They were full-scale industrial makeovers. Entire factories partnered with FDR’s administration and reimagined themselves for the singular purpose of achieving the national goal. The method for achieving that goal was secondary.

And it worked. Not because everyone agreed on the politics but because everyone agreed on the goal. And the government made it profitable to help achieve that goal. The system rewarded those who helped achieve it.

America became the Arsenal of Democracy not just through sacrifice but through consensus. The right incentives produced the right results in the timeframe we needed.

Fast forward to today. If we want prosperity for American workers, if we want families to thrive without leaning on public assistance, maybe the answer isn’t another patch or another tax. Maybe it’s the same principle. Let’s reward the businesses that help us achieve our national goals.

If a business pays livable wages, covers worker healthcare, and doesn’t push its costs onto taxpayers, what are we taxing them for?

In the end, it’s not about the method. It’s about the national goal of any worker being able to work for and achieve food on the table and heat in the house, all without taxpayer support. If we can achieve our goal, the method is irrelevant.

If Low Wages Are a Business Model, the IRS Should Send a Bill

Business taxes bring in less revenue than the cost of low wages. So, maybe we’re taxing the wrong thing.

Let’s take a closer look at the numbers.

In 2024, the federal government brought in about $4.9 trillion in revenue. Out of that, corporate income taxes made up just 10 percent or around half a trillion dollars of that five trillion.

At the same time, low wages cost the American taxpayer far more than half a trillion dollars a year. They cost about a quarter of the entire federal budget or 1.25 trillion dollars.

When companies pay poverty wages, workers still need to survive. No matter what, people need food on the table and heat in the house. We have all agreed to this principle. Both parties have expanded social programs to help people meet these necessities.

Because we all agreed that people need to be able to work for and achieve food on the table and heat in the house, these programs become mandatory funding. Mandatory means we must pay them. So, mandatory taxpayer-funded social programs kick in. These programs, including Medicaid, SNAP, housing aid, and refundable tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit, are automatic payments written into law. If someone qualifies, the American taxpayer pays.

In 2024, nearly 25 percent of all federal spending went to these kinds of programs. Much of this deficit is wage-related. Medicaid alone serves millions of low-income workers, especially in food service, retail, and care work. The EITC is specifically designed to supplement low wages with taxpayer dollars. In short, the federal government spends far more cleaning up after low wages than it ever collects from taxing business profits.

But rather than be angry at the state of the world, we need to figure out a healthy path forward.

So here’s the question. If a business pays its people enough to live, doesn’t push its labor costs onto taxpayers, and supports self-sufficiency, should we tax that business at all?

Because right now, we’re taxing good businesses and subsidizing the bad ones. And that makes no sense.

But … we also can’t raise the minimum wage to mandate the change. Just like FDR couldn’t compel businesses to get on board to achieve national goals, we can’t compel businesses to eliminate the need for taxpayer-funded social programs by asking nicely. When we needed Ford Motor Company to build B-24 bombers, we had to incentivize the change.

If businesses don’t increase revenue, they can’t raise wages. Mandating higher wages leads to job losses, not higher wages.

Two Studies Arguing Past the Point

It’s been a year since California raised its minimum wage for fast food workers to $20 an hour. And, of course, some sources claim the wage increase mandate is killing businesses, and others claim it had no negative effect.

First, a study conducted by the Berkeley Research Group, dated February 18, 2025, found that nearly 9 in 10 restaurant operators cut employee hours in the first few months. A third reduced benefits. Most said they planned to cut even more over the coming year.

Jobs declined. According to federal data, C