„Во потрага по најденото време: 50 години старото патување на еден фотограф низ Македонија“

Description

На првата годишнина од подкастот „Обични луѓе“, епизода број 17 која раскажува приказна која долго чекала да биде обелоденета. За американскиот фотограф Нил Фолберг, кој во далечната 1971 поминал неколку месеци во Македонија, и од тука понел повеќе од 400 ролни филм. Дури сега, педесет години по нивното создавање, тие се објавени во форма на книга.

Верзија со македонски/англиски титл на Youtube

Забелешка: „Обични луѓе“ е подкаст наменет за слушање. Во него е вграден голем труд за монтирање, музичка илустрација и течна аудио нарација. Транскриптот е наменет само како помошно средство, особено доколку архивските материјали се со понизок квалитет. Во сите други случаи ве поттикнуваме да ги слушате, а не да ги читате епизодите. Ви благодариме.

С2Е7 Транскрипт

Intro

Васка Илиева – „Ајде ред се редат кочански сејмени“ (од компилацијата „Билјана платно белеше“, ЛП, издадена 1971 oд Југотон)

[Neil Folberg]

Folk music always spoke to me. This is how I came to Israel too. It’s the same thing. I loved the music, it spoke to me, it tells a story. And it gives the spirit of the people in a way no other music can. It is not contrived; it comes from the people. And it was that music that drew me to the Balkans in general and to Macedonia in particular. There was something about the Macedonian music that was so strong and vital that I felt there had to be something deep and beautiful there to see. And I go by my feelings.

[Ilina]

Ова е Нил Фолберг, денес 71-годишен американски фотограф, кој живее во Израел. На неговите прекрасни фотографии од Македонија од 1971 неодамна налетав случајно, на интернет. Првата помисла беше – како е можно никој тука да не ги видел, цели 50 години? Зошто до сега немало изложба, студија, каква и да е промоција на постоењето на една ваква вредна збирка?

(Common People)

Jaс сум Илина Јакимовска. Во оваа епизода од подкастот Обични луѓе ќе се обидеме да ја раскажеме оваа долго одложувана приказна. Останете со нас.

(музиката продолжува)

[Ilina]

Пред педесет години Нил бил млад студент по општествени науки, со силен интерес кон уметностите. Но во тоа време не било баш лесно да се мешаат дисциплините.

[Neil]

I was a student already at the University of California, at Berkeley, I’d been studying sciences and I’d decided to switch to, essentially, photography. But as I described, it was an academic University, this wasn’t a place to study art. But it had other strengths, it had a…like a good department of Slavic studies, including an excellent instructor in Serbo-Croatian, not Macedonian, but аn instructor in Serbo-Croatian, of course Macedonia was at that time a part of Yugoslavia. And I got interested in the whole region through folk music, I always liked folk music.

[Ilina]

Нил го имал посетено Балканот претходно, престојувајќи месец и пол кај семејство во Сплит, Хрватска. Со пријател патувале низ регионот. Maкедонија го маѓепсала – за него тоа било земја на едноставни, чесни луѓе, каде сакал да се врати. Но за тоа морал да смисли добар план.

[Neil]

When I decided to move to photography I was looking for a project. I felt that the best thing you could do is to do a project. And Berkeley at the time was in a midst of a student revolution, you know about this, they were interested in radical politics. I was not interested in radical politics, but I was interested in sort of a comprehensive view of education where it wasn’t just one thing that you studied, but everything together, to make connections. So, when I decided that I was to make a photographic project, my first thought was, okay, I’d like to do something in Macedonia.

Тhe University opened up a program where you could make your own individual curriculum. It wasn’t even an individual major within a specific college, you could actually, essentially create a college. And something that wasn’t part of a university discipline. And I’d heard about that course, I signed up for it and by that time I was connected with, I’d been studying privately with an American photographer Ansel Adams, he is very famous, very well known, and there was another photographer, of tremendous stature, less well known, at Berkeley, within the department of architecture and design: his name was William Garnett. So I said why don’t we make a proposal, that I should do a series of photographs in Yugoslav Macedonia, differentiating it between the parts that were in Bulgaria and Greece. I wasn’t capable of dealing with so much at one time, and that would’ve been politically difficult as you could imagine.

[Ilina]

Со комбинација на добар предлог, солидни референци и чиста среќа, проектот на Нил е единствениот од педесет кој е одобрен. По долга административна процедура на добивање работна дозвола, преку тогашниот југословенски конзулат во Сан Франциско, тој се качува на авион, најпрвин до Белград, потоа до Скопје. Во тоа време кога се слетувало на скопскиот аеродром, пистата најпрвин морала да биде расчистена од овци.

[Neil]

The first thing that I did when I got there, I had met a family the first time I was in Macedonia, I had met a family there and Kosta Bozinovski, who picked me up hitchhiking. He was a government driver and he had a government car and I was hitchhiking I think from around, we come down from the mountains from Galichnik, and we were on the main highway and we were heading towards Skopje. And he picked us up.

[Ilina: With a government car?]

With a government car, which I think he was not supposed to do. I guess we looked interesting and he was a very friendly man, so he took me to Skopje and he invited me to stay there and he said if you ever come back you can come to stay with us. He gave me the address and I think I must have stayed. I don’t know where I stayed for the first couple of nights, but then I went to look for him and asked if I could stay a while till I find a more permanent place to stay, so the Bozinovski family took me in.

<figure class="wp-block-image size-large">

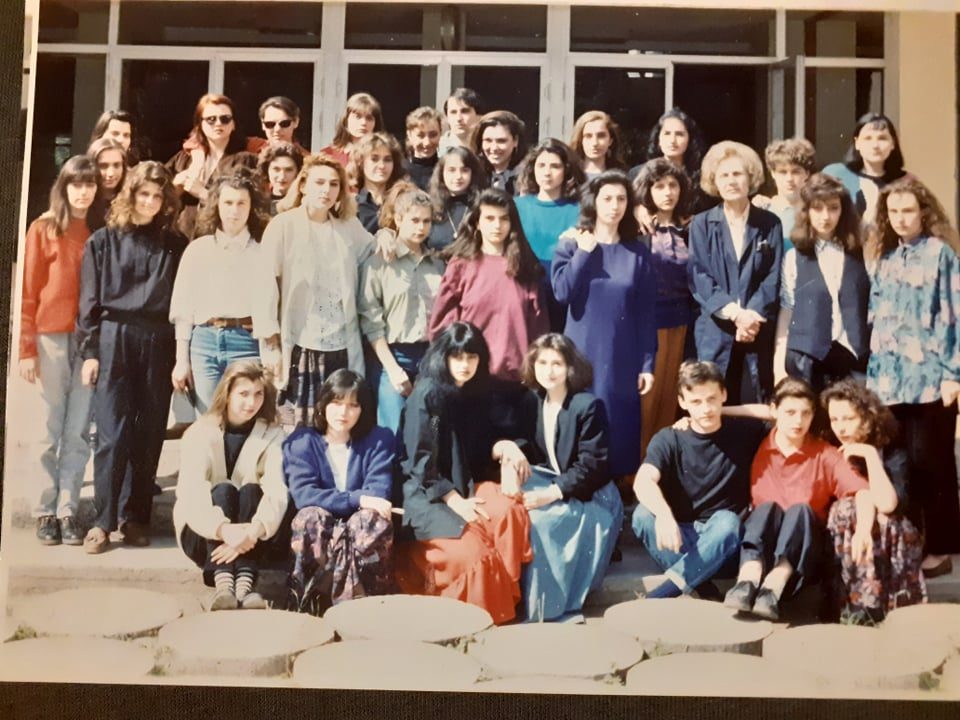

<figcaption>Галичник, 1971

<figcaption>Галичник, 1971© Neil Folberg</figcaption></figure>

[Ilina]

Семејството Божиновски живеело во пост-земјотресна барака, во која немало многу место. Сепак како добри домаќини му ја дале спалната а тие се преселиле во кујна. Подоцна Нил изнајмува соба со помош од некој „од горе“, веројатно за властите да го имаат полесно на око.

Во фокусот на Нил се нашле луѓето врзани за земјата, селата и малите градови. Списокот на места кои ги посeтил ги вклучуваат Битола, Кратово, Струмица, Делчево, Прилеп, Демир Капија…Галичник, Булачани, Маврови Анови, Косоврасти. Импресивен список дури и за млад патник низ мала земја. На времето ова значело многу возење со автобус, но и многу пешачење, како искусен етнолог.

[Neil]

From there I started just to explore the area, wherever I could get to on bus or by walking. I did a lot of walking and a lot of riding the buses. Everything was an adventure, I mean you could start anywhere…I had specific goals, I tried to get inside people’s homes, I was trying to photograph at least some representative sample of the population and I was interested in speaking to just ordinary people.

I wanted to make a coherent statement, a visual statement and so I came back to that idea that I started with, the idea of people on the land and I sort of neglected the photographs that I made in a more urban setting, in Skopje, which was of course the only real city in Macedonia. And I went and visited also all of the little towns, and I didn’t develop everything as much as I would have liked to, but I was fascinated by the relationship between the villages and the market towns where people took their produce, where they purchased the things that they couldn’t grow or create for themselves, and I probably, if I had been there longer, if I had more time, I would have followed that connection little bit more closely.

<figure class="wp-block-image size-large">

<figcaption>Јажар, Прилепска чаршија, 1971

<figcaption>Јажар, Прилепска чаршија, 1971© Neil Folberg</figcaption></figure>

[Ilina]

Бирократијата и надзорот од властите продолжиле. Сепак, Нил не го доживеал ова како малтретирање.

[Neil]

The thing that was nice about all of Yugoslavia was it was a very human, easy place and people were basically hospitable, even the officials, even when they became very difficult, never lost that human touch. So, sometimes I had very humorous encounters, sometimes they were difficult, and even occasionally a little bit scary, but that humanity was never lost. So, I had to have permission. You know in those days you had to have permission to photograph everything. If you wanted to photograph ‘spomenici’, what they called cultural monuments, then you had to have permission from the Government. If you wanted to photograph in the churches, you needed permission on the religious basis, and you had to have permission from each of the different administrative authorities. And, if I wanted to photograph people on the street, thеn I had to have permission from the Government to be photographing. They expected tourists to go and photograph tourist sites, and you could make photographs of people in, maybe, Bit Pazar, and you could make photographs here and there on th